When we pick up the newspaper from our doorsteps every morning, we do not usually stop to think how it got there. But newspaper distributors and the entire chain involved play a huge role in ensuring that we are connected to what’s happening in the world, through the morning dailies they deliver. Come rain, shine or even worse – the pandemic, their job of collecting and distributing newspapers never comes to a halt. They are indeed as vital as those who make and write the news. But unfortunately, the news distribution sector has always remained in the shadows with little government benefits or recognition.

Newspaper distributors, comprising 25,000 authorised agents, sub-agents/dealers and delivery personnel in Chennai have a weak social security net, simply because they are not included in any of the welfare boards, nor considered for any schemes by the Tamil Nadu government. “Five years ago, a newspaper distributor died in a road accident while on the job. The mainstream media reported his death. But the family received no financial compensation because there is no organised provision,” says M Dilli, Honorary President, Tamil Nadu Newspaper Distributors’ Association.

Read more: Do not stop press: Chennai printers lose business of 5.1 crore daily due to COVID

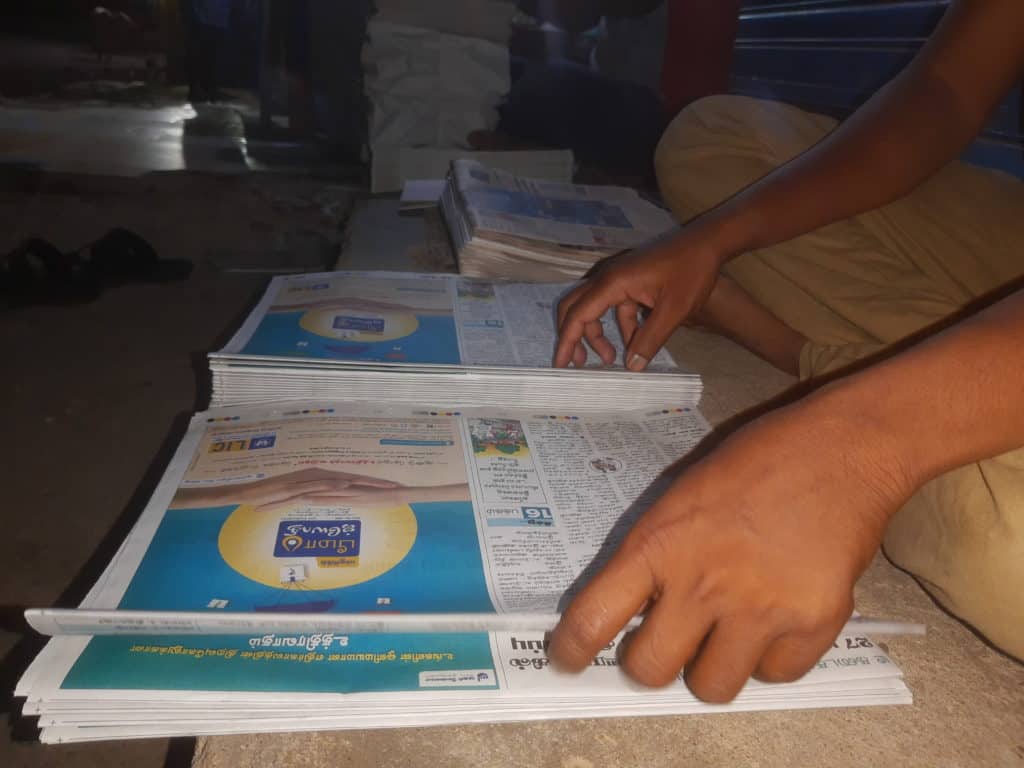

The chain

Newspapers are first picked up from the publishers by the authorised agent of the particular print media organisation, usually at a discounted price. The sub-agent/dealer, who is akin to a trader with no direct relationship to the media organisation, then buys the newspapers from the authorised agents. The final links in this chain are the delivery personnel, who get a monthly salary from the agents/sub-agents (depending on who employs them) and occasional perks, for example, a small amount when they place pamphlets inside the papers before distributing them.

Thus, a newspaper priced at Rs 5 is sold to an authorised agent at Rs 3. The sub-agent buys it for Rs 3.50 and the end customer pays Rs 5. “The agents or sub-agents add a service charge of Rs 1 on each paper. That amounts to Rs 30 for a month from one customer, a major part of which is used to pay the salary of the delivery personnel. Advertisers pay them a small sum for placing pamphlets inside newspapers,” says K Shankar, who works at the circulation department of Deccan Chronicle.

Difficult times

As dawn breaks, 35-year-old M Haridas, a newspaper agent for Mathrubhumi in Medavakkam gives a wake-up call to a delivery boy, who has not turned up yet. Other delivery personnel go on with their morning ritual of bundling various newspapers into a bag. As the sky is cloudy, they wrap the papers in a few sheets of polythene, just in case it rains. Business is anyway bad these days — it has been months since they got any pamphlets for advertisement and even the number of subscriptions has been falling sharply.

“From what used to be 5000 copies delivered by 15 personnel pre-COVID, it has now come down to a thousand copies with only three people on the job,” says Haridas, who has been in this profession for 15 years now. Why is he still sticking to the profession then? “Despite losses, this is one profession where there is a daily inflow of cash, as shops still buy papers. This money helps me sustain my other businesses,” he says.

Haridas also supplies water cans to households, for which he receives money fortnightly or monthly. Recollecting better days in the occupation, he says, “I did not need an alternative livelihood five years ago when newspapers were still the primary source of current affairs for citizens.” But things have changed. Today, like many of his contemporaries, Haridas lives on a meagre income, with debts piling up.

Life is even more grim for the delivery personnel. “I quit the job because my agent was neck-deep in losses,” says Sarath Mohan, a college-goer, who used to save the money received from newspaper delivery to pay his college fees. “I will resume work if the industry recovers. If it doesn’t, I shall have to quit studies and work full-time in some other occupation to keep the fire burning at home,” Sarath adds.

The COVID blow

The future does not look too promising either for newspaper distributors, as more and more publications — both national and regional — pull the shutters on their print editions and switch to digital media. During the first quarter of the financial year 2020-21, major print media players witnessed a sharp revenue decline of over 67% year on year, according to a September 2020 analysis by the firm India Ratings and Research (Ind-Ra). This was the outcome of a 76% drop in advertisement revenue and a 32% drop in circulation revenue, the report said.

The subscriptions for newspapers had begun to fall even before COVID, around five years ago, with the advent of digital media in a big way. Yet, there were some still loyal to their morning paper. But, COVID gave more reasons for readers to give up on newspapers. The fear of contracting the virus forced even regulars to switch to online consumption of news.

“The online subscription to the popular dailies is way cheaper and gets me more news articles from around the country than the hard local edition; why, then, would I want to subscribe to the latter?” asks Giri Kumar, an avid follower of current affairs and news. Besides, “how can one be sure that the delivery person will not transmit the virus?” he questions.

This trend is precisely what has been devastating for people like 29-year-old Muthu Kumar Kolanchinathan, who has been delivering papers at Sithalapakkam for two years now. Having seen his father in the business, Muthu Kumar followed in his footsteps. Four hours of work every day and an income of Rs 4000 a month provided a good part-time income for Muthu Kumar. He also holds another job but that fetches him a measly income. So when the number of subscriptions fell, his monthly earnings took a big hit.

“A year ago, I used to deliver 125 papers a day. Today, it has come down to just 35,” says Muthu Kumar, who now earns around Rs 1000. His earnings are just enough to cover his expenses on petrol, but his undying hope for a better future in the industry keeps him going.

Read more: How’s your neighbourhood grocer surviving the second wave?

A missing social security net

What has hit newspaper distributors particularly hard is the lack of support and empathy. Despite the obvious slump in the business because of the pandemic, they received no help from the government. Relying on debts from sharks, they now hope against hope that the print media industry will revive itself enough in the future for them to resume earning a living in the sector.

This is the hope that keeps Ranjithavalli Rajesh, a newspaper deliverer turned agent, going. Despite losses, she hopes that things will improve once the pandemic is over and maintains that she has no regrets for choosing the profession despite all its uncertainties. “If not for the heydays in this profession, I would not have been able to ensure decent education for my children,” she says.

Not all are as hopeful, though. Many say they have lost business to the extent of around 30% or more, as many long-time readers cancelled subscriptions, fearing contraction of the virus. Government and private offices functioning with just half the capacity saw no point in ordering newspapers any more — they too needed to cut down on costs. Pamphlets from advertisers, previously a good revenue source for the distribution industry, also dried up as the economy collapsed.

Unlike for other sections of the working class, no relief measures or compensation was announced for newspaper distributors. While accredited journalists were eligible for Rs 5000 as COVID relief compensation from the state government, there was nothing provided for distributors. “That’s because we are not categorised as frontline workers. If a journalist, who writes news by going to the field is a frontline worker, why shouldn’t a delivery person or a sub-agent, who works on the ground every day without taking a day off, be considered the same?” asks M Dilli.

“An identity card from the media organisations or the state government could have made our lives easier during the lockdown. Many times, police have restricted our movement as we had no identity card. An identity card can induce a sense of ownership too,”

M Dilli, Honorary President, Tamil Nadu Newspaper Distributors’ Association

Thus, except in the few odd cases where they received some voluntary donations from readers and citizens to see them through the crisis, they were largely left to fend for themselves. “A porter has better benefits than I do,” says Thandavamurthy K A, newspaper sub-agent at Saidapet, adding that even the slightest help from the government could have kept his spirits high during this difficult time.

Why don’t newspaper distributors have a welfare board?

The labour department of the Tamil Nadu government provides various benefits to those registered in the welfare boards constituted for different categories of workers. There are 17 welfare boards for organised workers, such as agricultural workers, small farmers, auto drivers etc. There is also a welfare board for workers in the unorganised sector. Those registered on these boards receive marriage and funeral assistance, death benefits and other cash awards, as called for by circumstances. Over the past one year, the Tamil Nadu government has announced monetary compensation for workers (including auto drivers and construction workers) registered in some of these welfare boards.

And yet, there is no such organised body to help newspaper distributors. “There are challenges. Many newspaper delivery staff are in fact children, which is a clear violation of the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986. There are also many part-timers in the profession, who hold other jobs,” said an official from the Labour Department.

There should be a way out, say experts. “The government should bring the distribution chain of newspapers agents, subagents, delivery personnel, cable TV operators and Internet service providers within the ambit of the board for unorganised workers. The move will greatly benefit these workers, who have always been deprived of government schemes and assistance. It will also help them procure loans and insurance,” says D Rajkumar, Head, Distribution, The Hindu Tamil Thisai.

“Respective state governments should gather the data of those working in the distribution chain. Providing financial security to newspaper distributors will help them repay the debts they have incurred over this period and tide through the crisis,” said Vipin, member of Newspaper Society of India.

While the distribution sector across the country shares the same plight as in Chennai, the Tamil Nadu government can act as a pioneer in formalising these workers, adds Raj Kumar. This last link in the chain of newspaper distribution is crucial to the media industry as a whole. With the entire sector reeling under heavy losses due to the pandemic, it is all the more critical to ensure that their welfare and continuance in the occupation are ensured.

Breezy style of writing with facts and figures makes an interesting read

Timely article. The newspaper delivery boys deserve a better deal. The publishers of the newspapers should play a vital role in this regard.

During fun times in our school days in seventies, postman was described as one whose arrival is eagerly looked at but whose departure is seldom noticed. This holds good for newspaper delivery boy.

Fax, E mail, SMS have numbed the role of postman. Same applies to delivery boy of newspaper as news of the morning is not as hot as it used to be due to 24 hour news channel and online edition. Yet to have a newspaper in the hand along with morning cup of coffee is a refreshing moment to kick start the day’s activity with joy and ecstasy.

Most delivery boys do it in the morning and rush to another work in the day. Hence earnings through this work is supplemental and not bread winning.