It has been six years since the launch of the Smart City Mission in 2016. Yet its core idea, of creating a participatory model for urban governance, remains elusive. Especially for the urban poor.

If people had hoped for a better managed, inclusive city with sustainable and resilient infrastructure, that hope has been cruelly belied. Plenty of projects under the Smart City mission are underway in many cities. But few have achieved the objectives they set out for themselves.

Which raises the question, what does the smart city mission provide for the urban poor? Have their lives changed at all despite the crores of rupees spent on such projects?

Not for the better, according to Besu Jain, a vendor who sells posters in Delhi’s posh Connaught place. “We haven’t seen anything under the NDMC Smart City Mission that is beneficial to us,” said Jain. “Instead, more than 50 vendors in Connaught place and the NDMC area have been evicted in the name of Smart City”.

The NDMC case

Let us try to understand this issue through a case study of the New Delhi Municipal Corporation’s Smart City Pvt Ltd (NDMCSCM).

Read more: Opinion: Nothing smart about Centre’s Smart Cities Mission

NDMCSCM’s official portal says that there is no particular definition for Smart City and its conceptualization varies depending on the regions, people’s aspirations, needs, etc. According to the website, “urban planners ideally aimed at developing the entire urban eco-system, represented by the four pillars of sustainable development — institutional, physical, social and economic infrastructure.”

Additionally, the goals stated under the mission include the enhancement of urban mobility, citizen-led planning, inclusivity, social development and setting the global benchmark for the capital.

To execute the mission and goals, a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) was created, the

NDMC Smart City Limited. It was incorporated on July 16th, 2016 with equity contribution from NDMC and the union government.

Poor choice

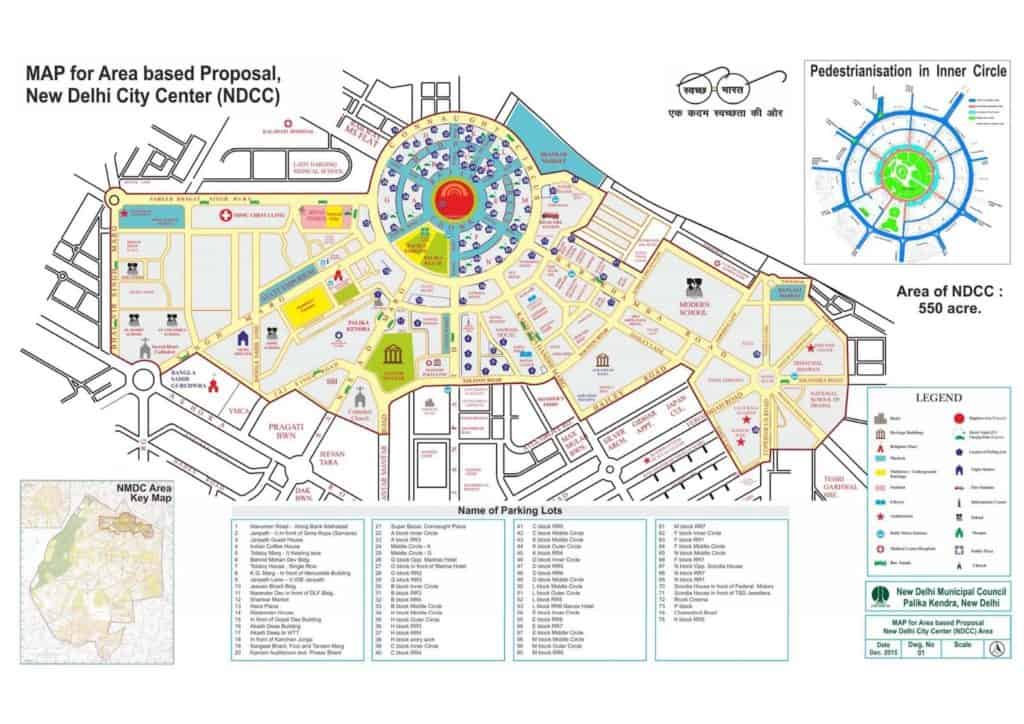

There are two components of the Smart City Mission, area-based development (ABD) and pan-city projects. The strategic components of area-based development are city improvement (retrofitting), city renewal (redevelopment), and city extension (greenfield development) plus a pan-city initiative in which Smart Solutions are applied covering larger parts of the city.

In the case of the area under the former NDMC, the area chosen for ABD was Connaught Palace. One of Delhi’s iconic and swanky shopping centres and residences.

The reasons for selecting an already rich and developed part of Delhi for the ABD is not clear. Areas like Connaught Place, Janpath and nearby areas were designed by Robert Tor Russell and are among the most well-known colonial architectural centres in the city. Even for pan-city projects, the NDMC chose the area covering Lutyen’s Delhi

“There was no need to spend money in Connaught Place,” says Mahipal, a street vendor in the area. “It could be used to improve the quality of slums or other congested areas of Delhi, where even a single project can change many people’s lives.”

Delhi’s other municipal areas have many jhuggi-jhopri cluster colonies, all grappling with problems like housing, waterlogging, sanitation, drinking water, and other civic issues. The need to improve the lives of the urban poor living here were ignored while planning the mission.

Progress of the projects

A total of 106 projects were envisaged under the NDMC Smart City Mission, out of which 86 have been completed, nine are ongoing, four are at the tendering stage, and six are at the DPR stage according to the information on the web portal. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs released Rs 294 crore while Rs 200 crores were granted by NDMC in 2021-22 as mentioned in the economic survey of Delhi.

Under the ABD, the completed projects cover physical infrastructure (development of a happiness area — these are public spaces that have been transformed as a safe space for people to play and relax amid flower boards, statutes, water fountains), setting up of electric charging stations and social infrastructure like smart public amenities and health ATMs in NDMC dispensaries.

A new Charkha national museum was built besides installing solar panels on the roofs of various NDMC buildings, setting up a bio-methanation plant for waste management, initiating smart parking in Connaught Place and setting up Smart Bike facilities in public areas, to name a few. Plus 55 energy-saving smart electricity poles were installed in Connaught Place. The smart poles boast of air sensors, energy-saving LED lighting, and Wi-Fi connectivity.

The pan-city category projects are mainly related to boosting digital infrastructure and largely app-based. The completed projects fit into one of the themes of e-governance (NDMC app, e-office), grid energy management (solar power project, smart metering), water and waste management (modern nurseries, rainwater harvesting), smart education (smart classes, e-Granthalya) and smart health (Bike ambulance, e-hospital).

Details of incomplete projects were not available on the website as on July 2nd.

But the question is, will the urban poor, who are mainly migrant workers, construction workers, street vendors, and other daily wage workers, benefit from these primarily digital projects?

Ignoring the masses

The answer has to be a resounding no, as few of these people actually live in the NDMC area. It appears that in the name of making the national capital a global benchmark, the working class have been totally ignored despite the mission being described as a citizen-centric one. In fact, the projects have led to eviction of the urban poor and vendors with a promise of relocation which is yet to happen.

Aravind Unni, an urban expert who has been working on urban Issues for a decade now, said that Delhi’s Smart City plans present a classic case of failure of the smart city concept. “Most smart city interventions are for the middle and well off classes, for example, the redevelopment of government flats,” said Unni.

Read more: Why Shimla smart city projects worth Rs 2905 crore look destined to fail

An unpublished report by the Indo-Global Social Service Society (IGSSS) states that in 2019 people reported no or negative change in the NDMC Smart City area. The figures are based on a survey plus interviews done in about 10 smart cities across the country including Delhi. The final report prepared by the IGSSS attempts to understand the impact of smart city on urban poor. The draft is final but yet to be made public. We checked with IGSSS and they agreed that we could use the information.

The people were asked questions on citizen participation, e-governance, safety of women, housing, digitalization, and IT connectivity. All prime features of NDMC’s smart city projects. The responses revealed that in terms of inclusivity, not a single area-based project or even pan-city project focuses on inclusiveness of urban poor.

The Economic Report of Delhi 2021-2022 too highlights this lack of inclusivity. According to the report, about one-third of Delhi’s population lives in sub-standard housing, which includes 675 slum and jhuggi-jhopri clusters, 1,797 unauthorized colonies, old dilapidated areas, and 362 villages. Most of these habitations lack basic services.

Whose city is this, then?

The chosen area for the Smart City in Delhi, the second most populated city in the world at 19 million, represents just 1.3% (2,57,803) of the total population of the city and only 2.9% of the total area. The area has no colony as such housing the urban poor.

“Smart city planning in Delhi is very problematic,” said Tikender Singh Panwar, former deputy mayor of Shimla and currently Convenor at CITYZENS.

“The majority of pan city projects are solely data-oriented and AI-based,” Panwar pointed out, “They are only helping big corporations. Smart City planning was never participatory and there is not a single project which has even slightly impacted the lives of marginalized groups. Not even 1% of the whole Smart City Planning is designed to make the capital city climate-friendly in any way”.

Aravind Unni added that the scheme needs to be rethought and needs to include the important role of urban local bodies for inclusive and sustainable urban planning and development. “There should be separate budget specifications and programme guidelines to ensure that smart city plans address the needs of the urban poor”.

Also read:

- Smart city Bhubaneswar yet to get proper wastewater treatment infrastructure

- Smart city Dharamshala aspires to be more than a picturesque spiritual retreat

- Commercial Street mishap: Why crores were lost for a Smart City project

- Several mega projects lined up; a transformed Chennai in just a few years: Smart City CEO Raj Cherubal

Good piece

hetal good piece