Marian D’Costa of Aiyo Patrao, an online kitchen that serves Goan and Kerala delicacies in response to orders received on Instagram, faces a stiff business challenge today. “Sourcing fresh fish at good rates has become increasingly difficult.” she says. Marian echoes what a large section of the huge fish-loving community in Mumbai and its suburbs have been feeling and what holds strong connotations for the fish economy in Mumbai.

Fish used to be a staple in most East Indian, Koli and some Maharashtrian households. All kinds of fish from shellfish, the bigger varieties like King fish, silver and black pomfret to smaller fish like anchovies and mackerel were consumed pretty regularly. But the state has witnessed a price surge, increased demand and decreased supply in locally consumed fish in the past three years. Untimely rains and soaring fuel prices have left a huge impact on the fishing industry.

Broadly speaking, many factors are to blame for the change in the fish economy, not just price hikes. Ocean pollution, overfishing, the e-commerce boom, closure of fish markets in the pandemic have all played a role in determining the patterns of fish consumption. People’s access to fish has changed over time, not only in terms of the fish they buy from markets, but also what can be sourced from the oceans.

What affects supply?

“The fishermen and fishing boat owners have not received their annual diesel subsidy for the past four years,” said Ganesh Nakhwa, a fisherman and the previous Director of Karanja Society, a fisherfolk union in Colaba. Depending on the size of the boat, subsidies can range from 50,000 rupees to 3.5 Lakh rupees. To some fishermen, the government currently owes about Rs 14 – 15 lakh in subsidies alone.

“No welfare schemes were efficiently implemented for the fishing industry in the pandemic, even though our income was completely cut-off. It is really troubling to see the Government’s inconsiderate attitude towards the fisheries industry,” he added. The rising cost of sourcing fish has affected the quantities of the catch as well as the price at which it is sold.

According to Ganesh, there has been a gradual decline in the number of fishing boats out in the waters. Reasons range from fuel price hikes to lack of infrastructure and government restrictions that determine how many boats can operate within certain radii of the coastline. “Whatever little infrastructure we have for parking boats is all built by the British, there have been no new facilities since then. There are no landing centres for Mahim, Worli, Versova and Madh Island fishing boats,” Ganesh told me.

The decline in the number of fishing boats inevitably affects supply; however, the demand has roughly remained the same in Mumbai. Which is why fish is now being imported from Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal.

The quality of fish has declined too in recent years. Rising mercury levels in the ocean, industrial waste, plastic pollution are all contributing factors to this phenomena. Even though there are better storage facilities and preservation methods now, the quality of the catch itself has been compromised.

80% of Mumbai’s catch goes to wholesale markets all over the city, and to Goa, Mangalore and other cities. Only 10 – 20% of the fish is exported to other countries. “The fish isn’t good enough to be exported; the White Pomfret and King Mackerel are the most sought-after varieties of fish outside of India, hence they are the only ones that are imported in large quantities,” said Ganesh.

Read more: There are no fish in the creeks of Mumbai. What this means to the city

Is consumption also to blame?

Overexploitation of natural resources by human beings is one of the greatest pressures affecting the structure and functioning of marine ecosystems over the short term. Our choices have the ability to steer the demand, and subsequently the pressure on our oceans. Although fish is still in high demand, individual households are steering away from buying the more local, smaller varieties of fish that are seasonal and more sustainable. Higher demand for bigger fish like Pomfret and King Fish has made these species victims of overfishing.

According to a 2019 report by Subuhi Jiwani, originally published on the People’s Archive of Rural India, the time that trawlers and big big boats spend at sea has also increased over the years. Vinay Deshmukh, who was with the Mumbai Centre of the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI) for over four decades, was quoted saying, “in the year 2000, these boats would spend 6-8 days at sea; this rose to 10-15 days and is now 16-20 days.” This has added to the pressure on the existing fish stock in the sea.

Most fish consumers are aware that all fishing activities are banned in the monsoon season, and hence people try to avoid buying fresh fish during that time, but this knowledge is not enough. It is important to understand and promote informed, ethical and sustainable consumption of fish.

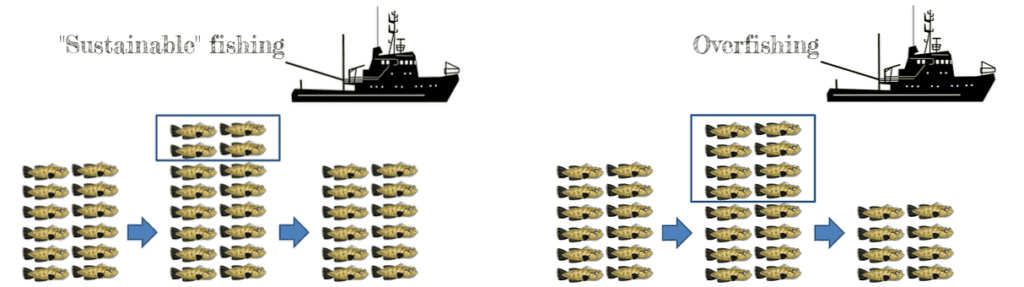

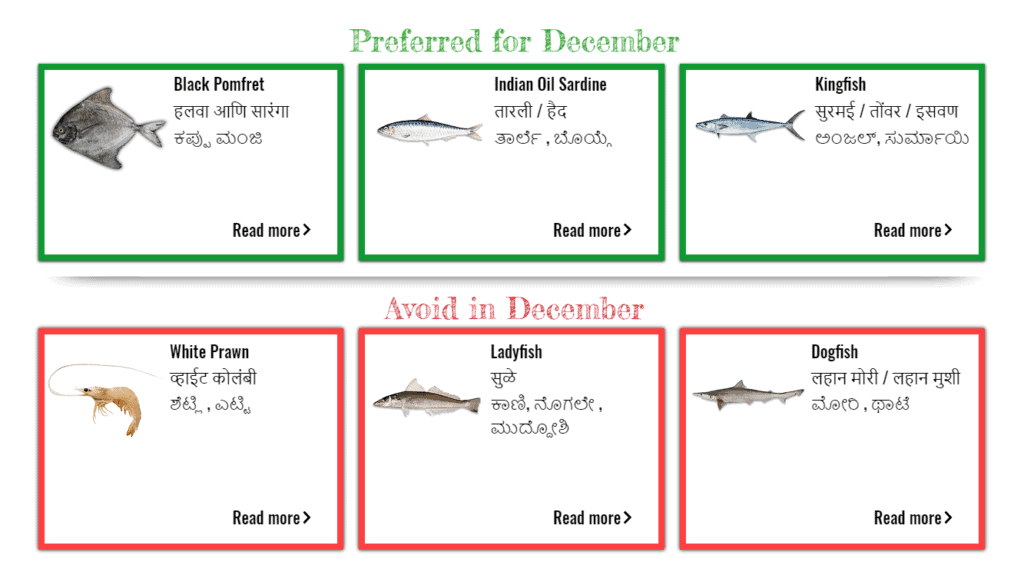

In 2017 a monthly calendar called Know Your Fish was launched to provide monthly updates for which fish to buy depending on the season. According to Know Your Fish, in the past two decades, it has been getting harder to get the largely consumed varieties of fish because fewer of them exist in our oceans. This has happened because the number of fish being caught is greater than the number of new fish being added to their wild populations. This is called overfishing.

The pandemic and its impact on fisherwomen

Buying fish in the pandemic was made a lot easier due to e-commerce sites. This brought respite to wholesalers and fishermen, as fish markets were completely shut.

Some fishermen started selling fish through Whatsapp networks. Juber Malkani buys fish from Malad fish market and sells at Aarey Colony. “I have a broadcast list of about 200 customers that buy from me regularly. I started doing this in the pandemic when I worked out a good deal with one of the Versova wholesalers.” said Juber. Juber’s success was largely due to the great deals he offered on fresh fish and word of mouth publicity.

Many fishermen started going to large societies and selling from their tempos. This helped them build a solid customer base by providing them at-home service. Huzaifa Malik, a fisherwoman in Goregaon East fish market, took to walking around the neighbourhood with a basket on her head selling fish as lockdown restrictions eased. “People now prefer buying from home every Sunday,” said Huzaifa, who goes on her regular route every Sunday afternoon, despite fish markets being open.

However, this adversely affected those who did not have the means to deliver in bulk or through online platforms. Historically, the distribution of labour in Koli families has been equal: men catch, women sell. But the pandemic created an imbalance in the ecosystem of the fisherfolk. The e-commerce boom primarily benefited the big players, those who could operate at a large scale. As wholesalers resorted to supplying to e-commerce sites, the fisherwomen who sold moderate quantities in the markets were particularly affected. These were women who catered to a more or less fixed clientele, and could not rope in new customers in the manner of those who moved to Whatsapp or door-to-door sales.

“A lot of the women here have to deal with jobless husbands, paying 200-300 rupees ‘hafta’ or rent to the market and not making enough profit on some days. This has led to rivalries amongst women in the market, each desperate to score a purchase. So you find them fighting for the best spot, or berating one another just to catch a customer’s attention,” said Lalita Patil, a fish seller at Goregaon fish market. “The hustle and bustle of Wednesday, Friday and Sunday markets is not as prominent as it used to be,” she adds.

Read more: Domestic fishing market sidelined, best of Mumbai’s fish exported

Some consumers however continue to remain staunchly loyal to the markets. Marian of Aiyo Patrao, for example, prefers going to the Mahim fish market. “We get more choices and better rates in Mahim market. Of course, it’s the best at Sassoon Docks, but that’s not very convenient for us,” she tells me.

“In the monsoons we would buy dried fish from Marol to last us through those three months of monsoon” said Rita Rodricks, a resident of Bandra for 62 years. “The fish buying and eating culture was very strong when I was younger. I grew up fond of cooking and eating fish, however I see fewer and fewer among the youth going to fish markets. Buying online sure is convenient, but the charm of fish markets in Mumbai is somehow lost,” she added.

However, the sheer nostalgia associated with the long history and the romantic idea of fish markets does not answer the question if we even need fish markets anymore. Will fish markets stand the test of time?