With a spike in positive cases being reported across the country, India is working towards containment of COVID-19 on a war footing. The number of COVID-19 positive patients across India breached 22,000 mark with more than 700 deaths. (as on 23rd April, 21:30 PM)

The National Health Profile of 2019 indicates that among the various major communicable diseases reported in 2018 across India, acute respiratory diseases had the highest share of cases. Experts suggest that people with medical conditions such as respiratory illness are at high risk of developing serious complications related to COVID-19. This suggests that our population is highly susceptible to coronavirus infection. It can further lead to an increase in the number of COVID-19 positive cases in India which in turn can overwhelm our health systems.

Moreover, dealing with increasing volumes of COVID-19-related waste is another risk faced by the frontline health care workers treating the infected patients. “Biomedical Waste Management during COVID-19 pandemic is a key element that contributes to overall public health protection and health care workers’ safety. It is not only a legal responsibility but also a social responsibility of all stakeholders,” says Dr Malini Capoor, Officer in-charge for Biomedical Waste Management, VMMC & Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi.

Sanitation workers collecting waste from quarantine homes and centres face health risks as the infectious waste generated from these locations can equally be hazardous and if not handled appropriately can increase the spread of infection. Media reports suggest that rag pickers were found to be collecting used face masks dumped as part of household garbage in some parts of the country. Sale of reused masks has also been reported at places.

In order to align safe management practices for biomedical waste and avoid discrepancies at the ground level, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) released a set of guidelines on March 19th. These were later revised on March 25th, because the waste related to home quarantine was not getting collected in most of the municipal areas. The guidelines were revised again on April 18, in view of further addressing the challenges faced by the waste handling community.

“The CPCB guidelines for management of waste generated during diagnostics and treatment of COVID-19 suspected/confirmed patients are required to be followed by all stakeholders like hospitals with isolation wards/ICU’s, quarantine centres, sample collection centres, laboratories, ULBs and CBMWTF, in addition to existing practices under BMWM rules 2016 as amended,” says Dr Malini.

Biomedical waste management crucial for avoiding further risks, but…

Biomedical waste (BMW) is defined as any waste produced during the diagnosis, treatment or immunisation of human beings or animals or research activities. More than 500 tonnes of biomedical waste is generated on a daily basis in India. Improper management and indiscriminate disposal of this waste causes a direct and serious health impact on the community, health care workers and the environment. Therefore, management of biomedical waste requires increased attention and diligence to avoid associated adverse health outcomes.

India has had Biomedical Waste Management (BMWM) regulations since 1998 to ensure safe handling and disposal of BMW. These regulations have been modified several times since then, until the new regulations were formulated in 2016 and amended subsequently. All these amendments and modifications were aimed at addressing implementation gaps while managing BMW. However, even after so many improvements made to the regulations, several studies unveil discrepancies on the ground.

A 2019 study conducted in 2019, by non-profit Toxics Link, across Delhi-based health care facilities (HCFs), highlighted that smaller establishments lacked in several aspects of safe handling and disposal of medical waste. Major gaps identified in the study were lack of protective equipment use, open waste storage areas, manual waste transportation within the facilities, improper waste quantum records and lack of accident reporting, among other issues.

Another CAG report of 2018 revealed that HCFs in Karnataka had resorted to unauthorised disposal of BMW. Given the history of recurrent malpractices prevalent throughout the country, it is even more important to monitor and ensure safe handling and disposal of COVID-19 waste.

CPCB guidelines for managing COVID-19 waste

According to Dr. Shyamala Mani, former professor at NIUA and Advisor, Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) “The CPCB guidelines will help in both reducing the danger of spreading COVID-19 through surfaces or touch or droplets and will also reduce the possibility of getting the non-infectious waste contaminated. This will keep the biomedical waste to be treated well within the limits and prevent health workers from getting infected”.

The specific provisions, as laid out in the revised CPCB guidelines, relate to the following points.

- Managing the waste at COVID-19 isolation wards, sample collection centres and laboratories

Biomedical waste is to be collected and stored in separately dedicated bins and trolleys that have an additional label of “COVID-19” for each waste category. This will help workers at the Common Bio-Medical Waste Treatment (and Disposal) Facility (CBWTF) identify COVID-19 waste and prioritise its treatment and disposal.

Both inner and outer surfaces of these containers are required to be disinfected with 1% sodium hypochlorite solution daily.

Further, the guidelines suggest that collected waste should be stored in a temporary waste storage area before handing it over to the CBWTF.

To enable timely collection and transportation of waste, HCFs should deploy a separate team of sanitation workers for both BMW and general waste within the HCF premises. It is advised that COVID-19 waste can also be directly picked up from the wards into CBWTF collection vans.

Non-contaminated waste is to be disposed of as per the specifications of Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016.

Record of waste generated from COVID-19 isolation wards has to be maintained separately while the operation of such wards and sample collection centres needs to be reported to SPCBs.

Feces and excreta from COVID-19 confirmed patient collected in diaper is to be treated as biomedical waste and should be placed in yellow bags. In case of use of bedpan, faeces to be washed into toilet and cleaned with a neutral detergent and water. It is to be disinfected with a 0.5% chlorine solution.

Used PPEs such as goggles, face-shield, splash proof apron, plastic coverall, hazmet suit, nitrile gloves are to be collected in red bag. Whereas used masks (including triple layer mask, N95 mask, etc.), head cover/cap, shoe-cover, disposable linen Gown, non-plastic or semi-plastic coverall are to be collected in yellow bags.

Viral transport media, plastic vials, vacutainers, eppendorf tubes, plastic cryovials, pipette tips are to be pre-treated as per the BMWM rules of 2016 and then be collected in red bags.

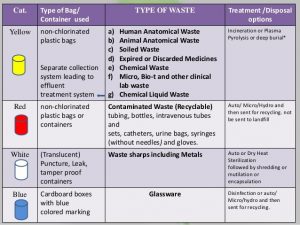

Some of the health care facilities were found segregating COVID-19 waste in yellow liners instead of the usual segregation into four colour-coded categories. In order to clarify the confusion, the CPCB guidelines clearly state that the segregation of biomedical waste should be carried out in the four colour-coded categories as per the provisions of BMWM rules of 2016. As a precaution, the healthcare facilities are advised to use double liners for each waste category to ensure adequate strength and prevent leakages.

Color coding for disposing bio medical waste as per BMW Rules 2016. (Source: CPCB)

- Duties of personnel operating or managing quarantine centres or homes or home care facilities

The guidelines describe what kind of facilities would come under the category of quarantine centres in order to facilitate smooth implementation of stated provisions. It also clarifies as to what type of waste generated from the quarantine centres or homes would be categorised as ‘biomedical waste’ and would be required to be handled or disposed of as per the guidelines.

In comparison to isolation wards, the quantum of biomedical waste generated from quarantine centres and homes or home care facilities is much less. Therefore, authorities suggest that the collection of this waste must be carried out in yellow liners that are provided by respective ULBs. These bags are to be placed in dedicated bins of appropriate sizes.

General solid waste has to be handed over to authorised waste collectors as identified by the ULBs or disposed of by prevalent local method.

The waste can also be given to the waste collectors or the CBWTF staff at the doorstep of quarantine centres or homes. Alternatively, it may be deposited at the centres established by the ULBs.

General waste from these centres or homes is to be disposed of as per the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016. Used masks and gloves from home quarantine or other households are to be stored in paper bag for a minimum of 72 hours after which these are to be disposed as general waste. It is advised to cut the masks prior to the disposal in order to prevent reuse.

- Duties of Common Biomedical Waste Treatment and Disposal Facilities

CBWTF officials are supposed to report to state pollution control boards (SPCBs) about receipt of COVID-19 waste from isolation wards, quarantine centres/homes and the laboratories. Similar reporting is required to be done across these wards and centres about the generation of COVID-19 waste. CBWTF has to maintain a separate record of COVID-19 waste.

People operating the CBWTF are mandated to look into regular sanitisation of their workers handling biomedical waste. According to the CPCB guidelines, these workers are supposed to wear personal protective equipment for their safety. A detailed list of necessary items to be worn by the workers while handling the waste includes triple-layered masks, splash-proof aprons/gowns, nitrile gloves, gumboots and safety goggles.

Regarding waste transportation from the point of generation to CBWTF, only dedicated vehicles are to be used by the workers, which are also needed to be sanitised with sodium hypochlorite or other appropriate disinfectant after each trip.

- Duties of State Pollution Control Boards (SPCB)

Before the first round of revision, the CPCB guidelines had briefly described the duties of SPCBs. These included maintaining separate record of COVID-19 waste, allowing CBWTFs to function for extra hours when necessary and not insisting on the authorisation of quarantine camps/ centres. However, after the revision, it now also describes the manner of waste disposal in cases of HCFs that may be situated in remote areas and are not connected to CBWTFs.

The disconnect between HCFs and the CBWTFs is a long pending issue. According to the CPCB’s annual report of 2018, there are less than 200 CBWTFs that carry out the final treatment and disposal of BMW. Most of the facilities that are not connected to CBWTFs are allowed to treat and dispose of their waste as per the prescribed methods and with due permission of the SPCBs. More than 20,000 HCFs have their own treatment facilities and more than one lakh facilities are connected to the CBWTFs.

“Guidelines are holistic, however, considering the poor operation and maintenance of CBWTF across the country, implementation can be an issue. In many districts, these plants don’t even operate properly and have inefficient collection mechanisms for biomedical waste,” says Swati Singh Sambyal, a Delhi-based waste management expert.

As a solution to the issue of disconnect between HCFs and CBWTFs, CPCPB guidelines suggest that facilities not connected to CBWTFs should identify nearest HCFS for disposing COVID-19 waste as per the 2016 rules and guidelines. Use of deep burial pits for yellow category waste has also been highlighted as a disposal option in the guidelines.

In case of generation of large volume of yellow waste, the guidelines state that SPCBs should permit hazardous waste incinerators present at Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facilities (TSDFs) to carry out the incineration of this waste.

- Duties of Urban Local Bodies

Responsibilities of ULBs were later added to the revised guidelines. ULBs have now been asked to provide yellow bags that are to be used for COVID-19 waste collection. Among other duties cited in the guidelines, ULBs have to maintain the record of all quarantine centres and homes and share the information with the SPCBs.

Additionally, ULBs have to ensure that the waste gets disposed of by the CBWTF or, when needed, it should get picked up by CBWTF at the doorstep of the quarantine camps. In order to facilitate smooth coordination, ULBs need to provide contact numbers of CBWTFs with the quarantine centres.

They also need to ensure that only authorised waste collectors collect and transport biomedical waste from the doorstep. A separate team is to be created for doorstep collection of waste from quarantine homes. The workers are to be trained on sanitisation, manner of waste collection and the precautionary measures to be adhered to while handling biomedical waste.

The ULBs have to ensure that workers are provided with necessary PPE and they wear it all the time while they are handling the waste.

Cleaning of the containers and vehicles used for waste collection and transportation is also to be fortified by the ULBs.

Apart from this, the ULBs are also responsible for ensuring that general waste gets handled as per the SWM Rules, 2016.

- Managing the wastewater from HCFs

As part of a latest revision, CPCB guidelines emphasize that HCFs and agencies operating sewage treatment should ensure appropriate treatment and disinfection of waste water.

Operators of effluent treatment plants or sewage treatment plants linked to HCFs or wards treating COVID-19 patients, need to adopt standard operation practices. Their staff is supposed to wear PPE and practice basic hygiene while on duty.

Use of treated water in the utilities of HCFs is to be avoided during the current pandemic.

The real win lies in successful source segregation

The guidelines have adequately stressed upon the specific roles and responsibilities of concerned bodies such as SPCBs and ULBs that play an eminent role in waste management. Aside from laying out the measures to handle waste at its source, the guidelines have detailed out on the ways in which it should be handed over to authorised personnel.

It is impressive to note that authorities have emphasised on the use of PPEs, sanitisation of collection bins and vehicles and appropriate training of staffs. Now the real win lies in successful implementation of these provisions on the ground. “In a scenario where even basic segregation of waste into wet, dry and domestic hazardous is not in place, segregation of biomedical waste from houses needs to be looked into carefully, especially, if the household is infected, which may lead to spread of infection to the waste collectors,” concludes Swati.

HCFs should segregate the biomedical waste in prescribed colour coded categories to avoid any manual waste segregation, post its transportation from the wards. In case of ordinary citizens, people should make sure they collect and segregate their general household waste into wet and dry categories thereby reducing infection risks to the sanitation workers.

Further in cases of homes under quarantine, residents should follow the protocol as provided by their local authority in terms of symptom reporting and self-isolation measures. They should act responsibly by collecting their waste in yellow bags and hand over to the designated sanitation worker(s).

RWAs can be instrumental in facilitating smooth coordination among their residents regarding the locally prescribed provisions to ensure infection control. This could be in terms of maintaining social distancing, practicing basic hygiene, ensuring regular sanitisation of common public spaces and adhering to the required waste management procedures.