Within a few days of the imposition of the nationwide lockdown in end March, the prices of fruits and vegetables rose perceptibly. As Chennai depends heavily on other districts in Tamil Nadu and other states for its supply of these foods, travel restrictions impacted the transportation leading to the price rise.

The pandemic has strongly underlined the need for Chennai to be self-reliant. But how can the city attain that self-sustainability?

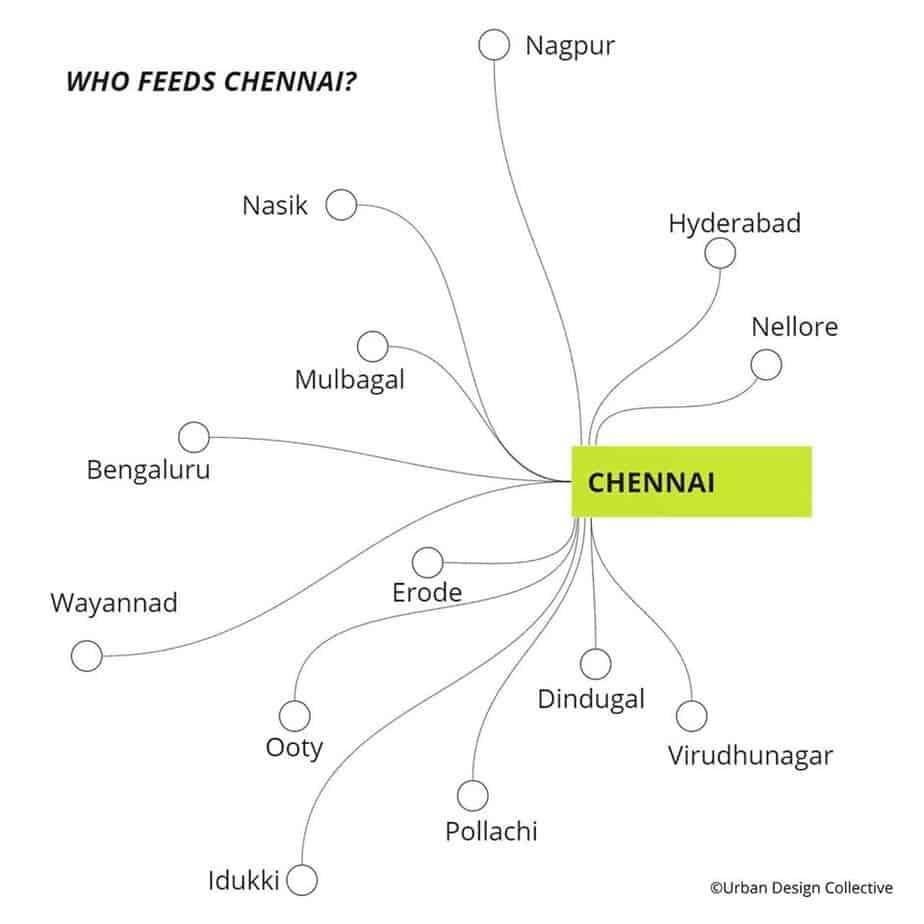

‘Who feeds Chennai?’, a body of research conducted by the Urban Design Collective (UDC) — a collaborative platform for participatory planning to create liveable cities — during the lockdown, provides ideas on how that can be achieved. The study throws up interesting insights on the food supply chain in the city.

We spoke to Srivardhan Rajalingam, an Associate at UDC, about the study and how Chennai could be transformed into a self-reliant, food smart city.

Where does Chennai primarily source its food from?

Traditionally, the supply to Chennai mostly comes from other states in India and some are also imported from other countries. Besides cities from Tamil Nadu, we receive supplies from cities such as Mulbagal, Wayanad, Nasik and Nagpur.

Primarily, all these supplies are unloaded at the Koyambedu market from where it is distributed to the retailers across Chennai and reaches the end consumer. Besides, there are just a few retailers in the city who do not rely on the market but have their own farms from where they source the produce to be sold.

What was the trigger behind the initiative?

COVID has left no stone unturned; considering that, we wanted to use the lockdown opportunity to understand the food supply chain. Our study, ‘Who feeds Chennai’ was mainly aimed to explore how the city could become self-sustainable. The same study was also conducted for Tirunelveli district in Tamil Nadu.

What lessons do the findings of your research hold for logistics, distribution and management of the supply chain?

Ever since the lockdown started, the food supply chain in the city has been transformed, mainly due to the travel restrictions. Home delivery service providers like Swiggy and Zomato began delivering groceries and fruits and vegetables besides cooked food.

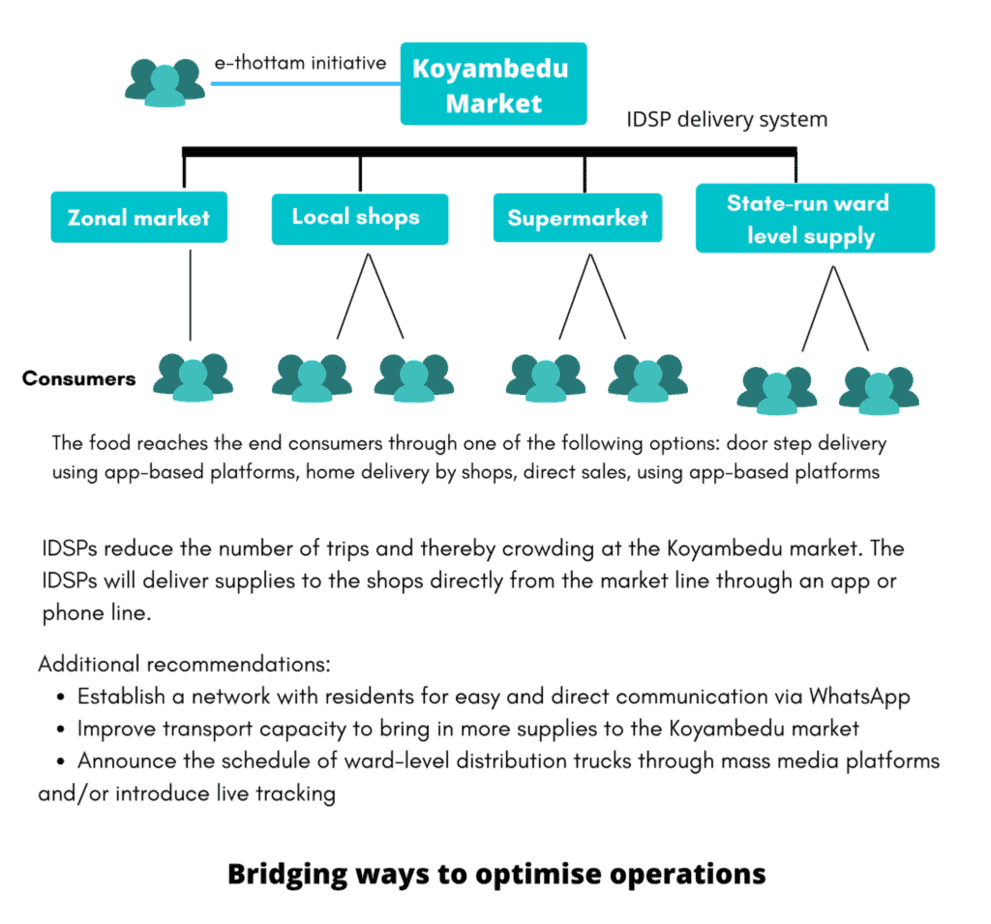

The State Horticulture Department introduced e-thottam for home delivery and the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) initiated ward-level supplies of vegetables in carts.

When the Koyambedu market emerged as one of the major clusters contributing to the rise of COVID cases in Chennai and Tamil Nadu, we looked at the short-term option of introducing intermediary delivery service providers (IDSPs). This way, the number of retailers visiting the market can be reduced; instead, one vehicle can transport the supply to 10 or 20 retailers in a neighbourhood.

This can be further coordinated by setting up a platform, that is not entirely digital, to connect retailers with the traders at the market. The mechanism can be implemented during situations that call for crowd control at the Koyambedu.

How can the city be self-sustainable post-COVID?

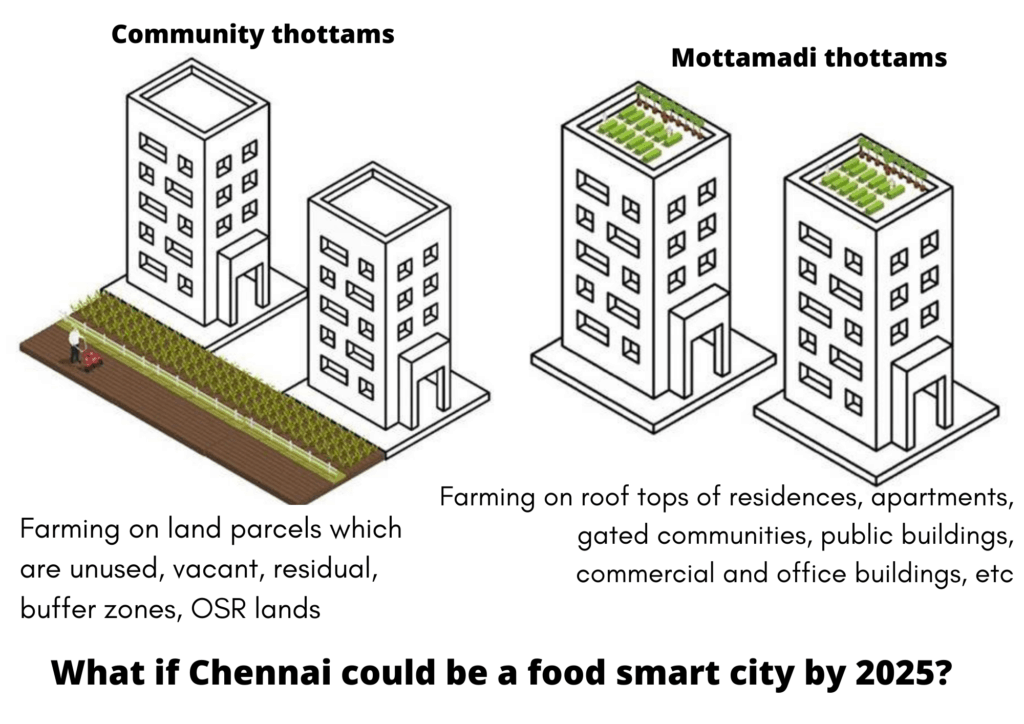

It is imperative that we move towards a new normal after the pandemic. The longer-term vision is to make Chennai a food smart city – making the city self-sustainable by locally producing fruits and vegetables – by 2025.

Making a city food smart does not require additional resources. The existing resources can be used to set up community thottams (farms) and motta maadi thottams (terrace farms). It opens up possibilities for public buildings, educational institutions and gated communities to grow supplies to meet the needs of their community.

What are the policy level changes required to implement urban farming in Chennai?

It is a multidisciplinary/multi-departmental approach. It can be taken up by independent farmers, RWAs and food businesses. The other way to implement this is through a top-to-bottom approach: a ward-level/pan-city initiative by the local body itself. Produce from the urban farms could very well be distributed to the Amma canteens all over the city.

Why should Chennai strive to be a food smart city?

- UDC’s research shows that a third of the supply is wasted during transportation, which could be reduced if we kickstart the urban farming programme.

- By implementing such projects, unused lands and empty plots can be used to set up community farms.

- It may open up farming opportunities for youngsters who can consider farming as a career option in the city itself without having the need to go to a village to practice farming.

- It can help the city move towards a circular economy.

- It can reduce carbon emissions arising from transporting food from faraway places.

How feasible is the project during summers and during periods of acute water shortage, which is not uncommon in Chennai?

The project would still be feasible and additional resources are required to make the farms sustainable.

A greywater recycling plant is a great alternative to fresh water for urban farming. Installing a recycling plant could be made mandatory, as in the case of Rainwater Harvesting (RWH). The idea of our project is to use every drop of water twice.

There are multiple ways of doing urban farming; hydroponics is one of them, which consumes less water. With this technique, farms can be set up indoors and temporary structures (glasshouses) can be erected to protect the plants from soaring heat.

Kerala has successfully practised this, although only at a neighbourhood or individual level. Similar healthy alternative practices can be adopted for sustaining urban farms in Chennai.

What can Chennai learn from other cities to become a food smart city?

Detroit is the city to derive inspiration and ideas from. The scarcity of fresh food retail in Detroit had left the city in an extremely precarious position. People struggled to source nutritious food, to stay healthy and prevent premature illness. But through urban agriculture and food entrepreneurship, Detroit has seen a tremendous transformation. They grow what they eat and are self-dependent.

If this possible i have roof terrace of 1000sq un used. How can i do ,what will investment cost and who will be my consumer

Very good idea. If this initiative is taken by the government itself, I think it should be easily achieved.

Hi, You may pl share connects in Tamil Nadu Horticulture department for Hydroponic

If this can be done, its really great for Chennaites

excellent article – worth reading the implementation of community gardening or terrace gardening requires constant motivation. Along with this, may be we can try cooperative system of vegetable growing and distribution (similar to Amul model)