For all outward appearances, Neelam (name changed to protect identity) has it all – a working husband, a couple of young and bright children, and a good job for herself. Look deeper, and one finds that her husband is an alcoholic who abuses her regularly.

Not having got his supply of booze since the lockdown started, he has become even more unbearable, screaming and shouting at her for little or no reason… He has also been encouraging their children to abuse her verbally.

Neelam is now worried that, with the government allowing sale of liquor, his abuse may take another form – probably physical. In addition to the mental trauma, Neelam now suffers from BP and other health issues.

Neelam’s is but one case in a country with around 67 crore women, although domestic violence is certainly not limited to India alone. The UN has in fact termed ‘violence against women and girls and COVID-19’ as The Shadow Pandemic.

According to the issue brief released by the UN Women titled ‘COVID-19 and Ending Violence Against Women and Girls‘, “Experience from the Ebola and Zika outbreaks shows that epidemics exacerbate existing inequalities, including those based on economic status, ability, age and gender… In the aftermath of the crisis, violence against women and girls will continue to escalate, at the same time as unemployment, financial strains and insecurity increase. A loss of income for women in abusive situations makes it even harder for them to escape.“

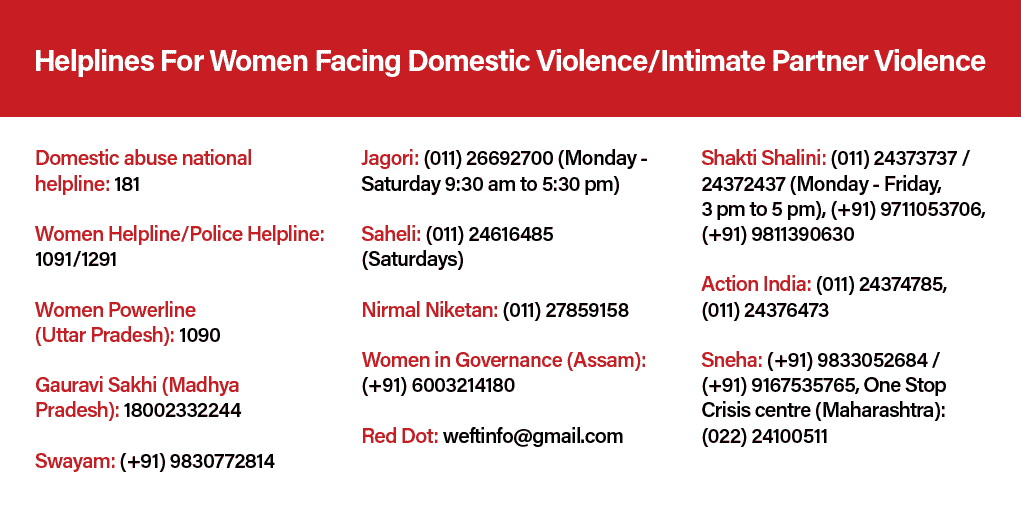

The number of domestic violence cases has apparently gone up to such an extent across the country that the National commission for Women (NCW) recently launched a WhatsApp number where the victims could report such cases:

The question to ask though is how many women can actually reach this number given that, as per a study by the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University published during late 2018, only 38% of women own mobile phones as compared to 71% men.

We spoke with Dr Rama Iyer, a Bengaluru-based advocate, from Legal Solutions, a law firm which has been involved in women and children related issues for over a couple of decades now to seek her thoughts on the scourge of domestic violence and how women could seek help, especially in these extraordinary times: Excerpts from the conversation:

Can you give us some inputs on what you have seen/heard about domestic violence in recent times (of lockdown)?

Before going into the problems faced by women in abusive relationships, during the lockdown or otherwise, let me tell you a little about a positive side to the current lockdown.

There have been a couple of calls from women who had earlier complained of domestic violence saying that this lockdown has helped them better understand and deal with things, and helped husbands/partners (those inflicting violence on them) too to better understand the situation of what it is to run the house. This was from women who are not regularly employed. A couple of middle class women called up and said that the abuse has actually come down because the partners are seeing what it takes for the woman to handle a household. Their husbands no longer think their wives are sitting idle at home all day.

However, there have been many calls asking for help with respect to domestic violence especially during these trying times. I would not call this out as a pattern, though, as I am talking only about the calls I have received.

I received a complaint from a lady whose husband threatened to physically harm her. She tried seeking help from the local police but was asked to call back later as they were busy handling the COVID situation in her area.

I told her to take some precautions on her own including sending an email to the police, calling the protection officer, contacting an NGO, calling a helpline, etc. In the current lockdown scenario, if she shouted for help, it may be a while before she actually gets help, even from neighbours who may hesitate before coming out of their house to do something. Given the virus scare, people will be scared to go to someone else’s house.

| Email id of the National Commission of Women: complaintcell-ncw@nic.in |

But the police are, in fact, stretched at this point of time, right? As are some shelter homes?

Indeed, the police force across the country is currently inundated with COVID-19 related work. Many shelter homes too are being used to lodge quarantined patients.

It would be pertinent to add here, though, that a petition filed by All India Council of Human Rights, Liberties and Social Justice has sought the Delhi High Court’s intervention to ensure adoption and implementation of immediate and effective measures to help victims of domestic violence and child abuse during the lockdown. It has been asserted in the petition that there is a horrific surge in domestic violence cases and even children are abused, as they are deprived of the networks that help them cope, such as friends, teachers, relatives, coaches etc.

A petition filed by All India Council of Human Rights, Liberties and Social Justice has sought the Delhi High Court’s intervention to ensure adoption and implementation of immediate and effective measures to help victims of domestic violence and child abuse during the lockdown.

What are the different forms of domestic abuse?

Domestic violence is not just about beating a person – physical abuse is just one form of abuse, which also includes sexual abuse. There are various types of abuse. It can be psychological (mental and verbal), ignoring the partner totally, verbal abuse – shouting, bad mouthing not only the woman but also her relatives or someone who is close to her, scolding the child so that it psychologically affects the woman and gaslighting which is a highly potent form of abuse.

Domestic violence can be economic too. Not providing for the dependent woman or child can constitute economic abuse. For example, a husband not providing money to pay the school fees of their child even when he has the means to do so would be considered as economic abuse.

The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 recognises different types of abuse. However, the various types of abuse cannot be put in water-tight compartments. Some women take abuse in their normal stride without even realising that they are being subject to domestic violence. But subconsciously, it keeps affecting them, and reaches a point where they finally snap.

The complete Act, The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005, can be accessed here.

So, who can complain? Can anyone facing any form of abuse access justice?

The Domestic Violence act says that an application (it does not say ‘complaint’) under Section 12 of the PWDVA, 2005 can be filed by the aggrieved person or someone on their behalf. The complaint may also be forwarded by the police, health professionals, the Protection Office etc. to the Magistrate.

Can you explain a little about the process of filing a complaint and some of the practical problems with respect to quick dispensation of justice?

The application has to be presented before the Magistrate in the form prescribed, or as near the form as possible. The Magistrate may pass ex-parte interim orders or may issue a notice. After appearance of the Respondent (abuser), they file their objections to the application under section 12, and also the interlocutory application (application for interim orders), if any.

The court may pass orders on the interlocutory applications for interim relief. The evidence is then recorded. Cross examination takes place of the witness/es. The court hears arguments from both sides and then passes the final orders.

In between, during the pendency of the trial, there could be many applications filed. For instance, for directing the Respondent/abuser or his employer or some third party to produce records, or for orders for certain directions etc, like payment of the child’s school fees, etc. It could be anything.

If the aggrieved woman should choose to lodge a complaint with the police, the procedure for doing so is as stated below.

The woman can give her complaint in writing. When filing a complaint, if the concerned police officer in charge refuses to register a first information report (FIR) about commission of a cognizable offence within his territorial jurisdiction, under Sec. 154(3), the informant can approach any senior officer of police or the Superintendent of Police or the Commissioner of Police with a written complaint.

If, after analysing the complaint, the officer approached is satisfied that the complaint discloses a cognizable offence, he/she may investigate the case himself/herself or give directions to his/her subordinate to register the FIR and initiate investigation.

If even after submitting a complaint to Senior Police officials, no FIR is lodged, then the informant is legally entitled to file a complaint with the Judicial Magistrate/ Metropolitan Magistrate u/s 156(3) read with Section 190 of the criminal procedure, thereby requesting the FIR to be registered by the police, and commencing investigation into the matter.

If the concerned police officer in charge refuses to register a first information report (FIR) about commission of a cognizable offence within his territorial jurisdiction, under Sec. 154(3), the informant can approach any senior officer of police or the Superintendent of Police or the Commissioner of Police with a written complaint.

The process seems straightforward. Is it working though?

What is happening on the ground is that domestic violence cases per se are becoming more like any other litigation.Thestatute was meant to provide quick relief to women in abusive relationships.

The Domestic Violence Act itself says that the Magistrate should try to dispose of the case within 60 days. But some cases take almost a decade for final resolution. One reason is the elaborate procedures followed by the courts. The Criminal Procedure Code is the prescribed code for domestic violence cases. This is actually a quasi-civil law and as per the statute, when a case first comes up before the Magistrate, he has to fix a date for hearing within three days from the date of filing. However, this does not happen many times. This stipulation is to ensure interim orders, ex-parte if necessary, are passed expeditiously.

Normally, if there is prima facie abuse shown by the Aggrieved Person and there is threat of further violence, the Magistrate should immediately, in my opinion, pass protection orders against the Respondent/abuser and in favour of the Aggrieved Person/abused to prevent any further domestic violence.

Protection order is a restraining order to prohibit or prevent the commission of domestic violence by the Respondent/abuser. For instance, if the Aggrieved person (wife/live-in partner and or child) and the Respondent are separated, but the Respondent goes to the residence or place of work of the aggrieved person, or the school where their child is studying, and causes physical violence to her or the child; or calls up/messages the aggrieved person and abuses her verbally, and the Magistrate is convinced about there being abuse, restraining orders are passed.

Can you tell us a little more about restraining/protection orders?

As mentioned earlier, the Magistrate should be convinced that there is domestic violence as alleged. The court, on perusal of the statements on oath along with maybe documents or any preliminary evidence that she might have produced before the court, or, at times, based solely on the affidavit by the Aggrieved Person/abused, may pass an ex-parte interim order of protection. These protection orders are one of the specialities of this Statute.

The court even has the power to ask a male Respondent to stay away from the shared household or matrimonial home to prevent violence.

Many a time, the abused and the abuser live in the same household, and the court does not pass protection orders; instead it only issues a notice to the abuser/Respondent to hear him and then decide if any order is necessary. In such cases, the purpose of the law itself may be defeated.

The abuser, on coming to know that that the aggrieved person has approached the Court, may in fact escalate the violence. The latter may even be thrown out of the house, thus making her vulnerable and susceptible to other abuse. So, according to me, if she has approached a court of law, and there is some material or even an affidavit to back what she is saying, the court should have a sympathetic and sensitive view wherein they check the facts and pass the minimum protections orders.

In many cases that is not done because domestic violence cases are taken as routine litigations, and the special nature of the statute is ignored. In such cases, notice may be issued which may take quite a while in getting served, negating the stipulation of 60 days for disposal of a case.

There are cases where notice is not served even after six months of filing the case.These are some of the practical problems that women who approach courts forrelief from the domestic violence face.

Legally, is there a difference between domestic violence and intimate partner violence?

The Domestic Violence Act, 2005, which came into force in 2006 recognized live-in relationships for the first time as a domestic relationship.

Intimate partner violence, as you put it and I understand it, is violence by a partner who is not a husband. If such a person causes violence to his partner, it would be construed to be domestic violence if the parties have shared a household. Persons that live-in together in the nature of marriage are also covered under the domestic violence act.

Live-in relationship is one where the couple has lived in together and shared a household. If a couple is in a relationship and meet once in a while in a hotel or such, but have not shared a household, they would not be considered as a “live-in couple” or one with a domestic relationship. Shared household is a must under the statute.

According to the current statue, the Aggrieved Person can only be a woman or a child. The Statute, as said earlier, defines the Respondent as a man or anyone related to him. This is a special statute for protection of women. The domestic relationship can be father-daughter, son-mother, husband-wife, brother-sister, etc. It could also include an adopted son, step-son, step-father, etc.

Persons that live-in together in the nature of marriage are also covered under the domestic violence act.

Who all can an affected person approach when subject to domestic violence? What are some of the precautions you can suggest given the current lockdown scenario?

The best thing to always do is to call the police, especially in case of physical violence. However, many women in a domestic crisis may not be comfortable calling the police, again due to the associated stigma, and the added apprehension of dealing with the police. In such a scenario, it is better they call the local women’s helpline.

In Bengaluru, there is Mahila Sahayavani (Toll Free # Namma 100 support) and also Parihar Family Counselling Centre. There are other organisations too across the country, as also many shelter homes and support groups. One needs to check though whether they are working during the lockdown.

| The Karnataka High Court has notified that in case of emergency, if the judicial officer feels that there is urgency, those cases can be taken up. As per a recent report, It has also asked the state government about the action it is taking due to the alleged spike in cases of domestic violence during the lockdown. Further, the High Court has asked that the state indicate helplines available across Karnataka where those affected by domestic violence can complain. |

Medical Professionals too, in case of domestic violence, can refer the aggrieved person to the authorities.

Then there are the Protection Officers (Child Development Project Officers or CDPO), who are the designated protection officers in Karnataka appointed under the Domestic Violence Act. Each jurisdiction has their own protection officer who can be approached in times of difficulty.

With courts now only taking up matters of urgency, the option available to the aggrieved person is to send an email to the Chief Magistrate. The email ids for the various magistrates can be found on the e courts website.

| The various stakeholders Role of Medical professionals – Inform the aggrieved person/woman about her rights – File a Domestic Incident Report (DIR) and forward to Protection Officer – Provide medical aid – in many cases, depending on the situation, this could in fact be the first step – Refer her to the Protection Officer (PO) Role of NGOs – Inform women about her rights – File DIR and forward to PO – Provide services like emergency shelter, medical care (if need be), protection, financial assistance (on a case-to-case basis), and counselling services – Refer her to PO Role of Police – File criminal case if woman desires – Help enforce court orders – Refer her to PO – Inform the woman about her rights Role of Shelter Homes – Inform woman about her rights – Provide refuge – Refer her to PO Role of Protection Officer (PO) – Inform woman about her rights – File DIR – Help woman access services – File court application for relief – Help enforce court order Role of Lawyer – File Application – Represent Woman in Court Role of Magistrate – Recommend counselling/mediation – Pass orders – Oversee Protection Officer |

What are the types of redressal one can seek under the Domestic Violence Act?

The aggrieved can, at any time, seek monetary relief, protection orders, and residence orders (especially now during lockdown, a woman should not be rendered shelter less). One can also ask for custody orders and compensation for the domestic violence suffered.

Should something serious come up, the aggrieved person can write to the Magistrate as mentioned above.

Excellent in-depth study with solution. The most needed tool.

Wonderful information for protection of women

The conversation with Advocate Dr. Rama Iyer about domestic violence and prevention is very informative. There is a need to disseminate this information more so that this information can reach the women of our rural areas, especially in remote areas.