Recently, a social media post revealed the shocking experience of a woman, who found a mobile phone hidden in the waste bin in the washroom of one of the Bengaluru outlets of a popular cafe chain. The phone camera was reportedly pointed towards the toilet seat and was recording video. The cafe states that the staffer who planted the phone was terminated and legal action was initiated against him. In another, more recent incident, a hidden camera was found in the women’s washroom of a college in Andhra Pradesh. The videos recorded via it were allegedly circulated among male students of the college.

These are not isolated incidents. A random sample of incidents of non-consensual capture of images and videos point to the need for a concerted crackdown on the use of hidden cameras for surreptitiously recording persons in places where they have an expectation of privacy — washrooms, changing rooms, fitting rooms, and hotel rooms, to name a few.

Capturing, publishing or distributing someone’s nude, partially nude or sexually explicit photos or videos without their consent, or threatening to do so, is called image-based abuse. In colloquial terms, we usually refer to such instances as “leaked photos/ videos”, “MMS scandal”, “revenge porn” etc. While its ramifications on victims are devastating and long-lasting, it is more rampant than is currently acknowledged in our public policy and social discourse.

Surreptitiously recorded images and videos have their own “supply chain”, so to speak. They are often sold for profit to pornographic websites, to networks dedicated to non-consensual pornography on messaging apps, or to extortionists who demand money, sexual favours or more sexual imagery from the victim in return for deleting or not distributing the images further.

Even if the person who originally recorded the images does not intend to distribute them, say, a voyeur who wants them for personal consumption, there is a possibility that the images may leak or be stolen from their device or online accounts, from where it may enter the supply chain.

(For more information about the modes of capture, access, publishing and distribution of non-consensual intimate imagery, strategies and tips for safeguarding oneself, and remedies available to victims, refer to the paper, Non-consensual intimate images: An overview.)

Read more: What you need to know to combat the deepfake menace

A few salient points to note

Image-based abuse is flagrant for a number of reasons:

There is apathy. Image-based abuse is not perceived as a serious sex crime. It is both a symptom and a consequence of rape culture. It rests on the belief that the bodies of women exist for objectification, for the pleasure and entertainment of men. The images of women merely going about their daily lives — showering, seated on a toilet, or in their own home dressed in booty shorts — become an ‘MMS scandal’, ‘leak’ or virulently-distributed pornography.

It is underreported for the same reasons that offline crimes such as rape and sexual assault go underreported. Conviction rates are low, filing a complaint itself may be a challenge, and legal processes can become lengthy, re-traumatising and expensive. Socially, victims suffer blame, stigma, humiliation and ostracism. Often, they may experience a backlash from their own families and communities for bringing the offence to light.

Read more: Have cities really made it easier for women to report crimes against them?

Perpetrators know this and it gives them a sense of impunity. Moreover, because it’s a tech-facilitated offence, a lack of digital literacy, know-how and skills and not knowing where and how to access help also prevents victims from taking steps to protect themselves and report incidents.

It is treated as a matter of personal safety, and not collective obligation. While it is prudent for everyone to be conscious of their personal safety, treating image-based abuse as solely a matter of personal responsibility is victim-blaming. It implies that victims should have seen it coming. It excuses the actions and intent of the perpetrator and distracts from the offence.

The victims get surreptitiously recorded not because they are gullible or negligent but because they were unsuspecting. They were in a place where they had a legitimate expectation of privacy. Women should not be expected to live their lives in a constant state of alarm and paranoia in order to be vigilant against such dangers always and everywhere.

It also ignores the fact that image-based abuse is a widespread and systemic problem. Often, it is an organised criminal activity with a variety of motivations, including the sale of images for profit and for extortion. Monetary gain is a major driver behind the proliferation of image-based abuse.

Privacy is an alien concept. India is not a culture that respects personal privacy or recognises its violations. A demand for privacy is equated with having bad intentions or something to hide. In general, there is no etiquette or sensibilities about seeking consent before photographing or videographing others and before posting the content online. It is a free pass for voyeurs.

What makes effective crackdown difficult?

There is no conclusive data. In the statistics published by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), the distribution of image-based abuse content is clubbed with the distribution of pornography. This method of sorting and logging offences makes it hard to discern incidents of image-based abuse from consensual pornography. There has been no independent and in-depth study on the incidence of image-based abuse in India.

A lack of data renders the problem invisible. Hence, it is harder to advocate for preventive and remedial measures from public and private entities and ask for a crackdown on its perpetuation.

It can happen anywhere. Some spaces are more likely than others to have hidden spy cameras, for example, “hookup hotels”, public/ shared washrooms and changing rooms. However, no place can be ruled out.

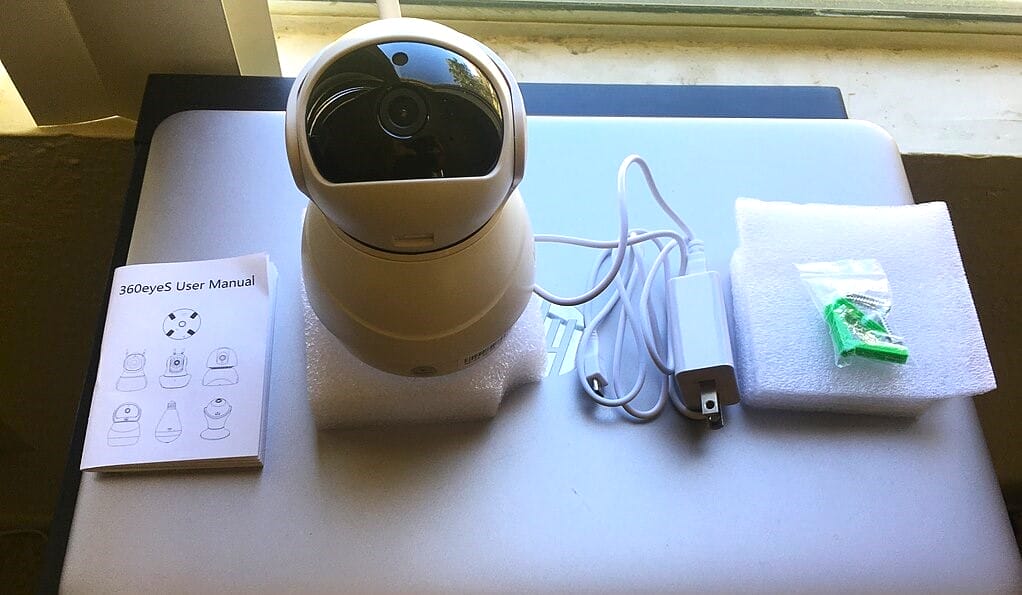

Spy cameras and microphones are cheap, easily available (See website selling spy devices) and can be purchased from offline markets without a paper trail in India. Spy cameras are incredibly tiny, some with lenses just one millimetre wide, and can be installed in places such as lamp shades and fire alarms. Some can transmit the images to a connected network. Sophisticated ones can record with clarity despite their small size and even in low light or in the dark.

What may be the solution?

Treat the non-consensual capture, creation (using generative AI tools), publishing and distribution of nude and sexually explicit images and videos, and threats to do so, on par with other sexual crimes. There should be stricter enforcement of the current legal provisions against voyeurism, sextortion, and violation of privacy. Lawyer Sapni GK elucidates on the requirement of a survivor-centric legal framework against image-base abuse in this article.

Research and data collection are necessary in India to understand the nature and incidence of image-based abuse, its patterns, perpetrators and impacts on victims in the immediate and long term. This should be done in ethical ways that do not harm victim-survivors further and treat them with the necessary sensitivity and respect. Helplines and NGOs may have their own data and should consider releasing anonymised datasets.

Law enforcement agencies should develop SOPs to regularly inspect public places, such as public washrooms, for hidden cameras. This requires radio frequency (RF) detection devices and training of personnel to use them as well as for other methods of detection such as infrared, Bluetooth and WiFi scanning and manual inspection for hidden cameras.

Private properties — hotels, clothing stores, places with washrooms or changing rooms such as swimming pools and gymnasia, paying guest accommodation, hostels, and student accommodation — should be advised to do their own periodic checks for spy cameras.

Government bodies should use signage, public service advertisements and awareness programmes online and offline to sensitise the public against image-based abuse. These may include creative solutions. South Korea is another country where non-consensual pornography is a rampant problem.

The Busan police once uploaded to 23 file-sharing websites a campaign video that seemed like a video shot with a spy camera. The video emphasises a common outcome among victims — suicide. The campaign, called “Stop Downloadkill“, ended with a message warning website users against downloading non-consensual, spycam pornography.

Regulate the import and sale of spy devices. A drawback of this is that spy cameras may have some potentially desirable uses, such as obtaining evidence of domestic violence or child abuse which may be defeated by the requirement of a paper trail of the purchase.

Police and judicial reform are required. Documented stories of survivors (see here, here and here) show that the police and judiciary do not treat the issue with the necessary sensitivity or seriousness and that victims hesitate to carry out even basic measures to take down the content or bring perpetrators to book.

All solutions to image-based abuse online and offline are those that aim to reduce apathy and victim-blaming and dent rape culture.

Guidance for victims

1) What should be the first step when one becomes aware of non-consensual use of their images?

Victims are devastated when they find that their images have been posted online or distributed without their consent. They need psychological and emotional support as the very first step. Some free helplines are Vanitha Sahayavani and Responsible Netism, which also provide guidance towards legal processes. Social and Media Matters can be emailed for support. (These examples of support providers in India are indicative and not exhaustive.)

Alternatively, victim-survivors may contact a private psychological counsellor.

Those who wish to seek legal recourse should, of course, file a police report. One-Stop Centres (OSCs) in some Indian states handle cases of technology-facilitated violence against women.

2) Is filing an ordinary police complaint (FIR) enough or does one necessarily have to approach a cybercrime cell?

Technology law and policy lawyer Sapni GK says, “The first step would be to go to the police station and register a complaint. It will be taken more seriously if not reported as a cybercrime, since this will more often than not include offences such as outraging the modesty of a woman, voyeurism, etc. in addition to the offences under the Information Technology Act, 2000. A complaint can be filed, following which an FIR will be registered.” Some of the challenges of filing a police complaint are noted in her article referenced above.

3) What legal remedies are available to a victim?

Refer to the section titled “Legal remedies” in the paper Non-consensual intimate images: An overview. Sapni GK suggests that “it is advisable to go to a practising criminal advocate with a strong background in offences under the Information Technology Act, 2000”.

4) Are there any digital best practices to follow to minimise risks of falling prey to image-based abuse?

Refer to the section titled “Strategies” in Non-consensual intimate images: An overview and the section titled “Damming downstream distribution” in this article. Social and Media Matters has published a toolkit against sextortion. A guide by the anti-virus software company Norton on “How to find hidden cameras”.