The third wave of COVID-19 in Mumbai has mobilised another round of crowdsourcing for hospital beds, akin to the second wave, when citizen action kept the country afloat. Among them, one citizen, Vikram Tuteja claims multiple people have asked him for help in their hunt for ICU beds. Even Iqbal S Chahal, Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC)’s commissioner, acknowledged complaints about the shortage of COVID-19 beds in private hospitals.

But, the BMC’s daily updates have continuously shown ample availability of hospital beds. The percentage of occupied beds has not exceeded 22% (7,500), even when there have been over a lakh active patients. Between January 5th and 9th, more than a 1000 people were hospitalised each day.

“Since more than 95% cases are being detected from non-slum areas, there is tremendous demand for beds in private hospitals,” the municipal commissioner said on January 5th. “Patients are reluctant to go to COVID Jumbo Hospitals and BMC hospitals.” Prominent hospitals like Nanavati, Kokilaben, Lilavati and Bombay Hospital were all full.

Raising caution about the potential surge in positive cases, Chahal instructed the city’s 142 private hospitals to ramp up bed availability to second wave levels. By January 10th, they were to reserve 80% of normal beds and 100% of ICU beds (at government rates) for COVID-19 patients. From 4,000, beds increased to 6,059 (on January 17th), with the possibility of an increase to 12,000 beds.

With slight increases in government facilities as well, total ICU beds have gone up from 2,583 to 3,176.

Incidental hospitalisations

Meanwhile, patients admitted for other medical reasons were testing positive for COVID-19.

“In the initial phase, people who were already admitted for a whole range of reasons, either a surgery, heart attack, stroke, etc, incidentally tested positive for COVID-19,” said Dr Lancelot Pinto, consultant pulmonologist at PD Hinduja Hospital. “We’ve had post-surgery patients suddenly get a fever and test positive. They can’t be sent home, so they are shifted to COVID-19 wards.”

Testing was made mandatory before medical procedures, with 70% of such patients testing positive and hospitalised, according to Dr Shashank Joshi, a member of the state’s COVID task force.

The municipal commissioner also identified that insurance policies were blocking beds. Non-serious patients, some of them seeking the monoclonal antibody cocktail, choose hospitalisation to avail their insurance cover, despite the possibility of the treatment in outpatient department (OPD) care.

Staff shortage engulfed hospitals, including government ones. “More than 100 doctors have tested positive at KEM and are recovering, so we are working at 6-8% of our manpower,” says Dr Sachin Pattiwar, president of Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors (MARD)-KEM, who was also sick. “We’ve also been working without our juniors for the past six months, because of the delay in the dates for counselling post-graduate candidates.”

JJ Hospital in Nagpada, too, had nearly 100 people infected, including faculty members and other healthcare professionals. 80 doctors were affected in Lokmanya Tilak Medical General (LTMG) hospital, Sion. In total, almost 500 doctors across government hospitals tested positive, affecting both non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 work.

Read more: What to do in case your child tests positive for COVID-19?

Is the peak forthcoming?

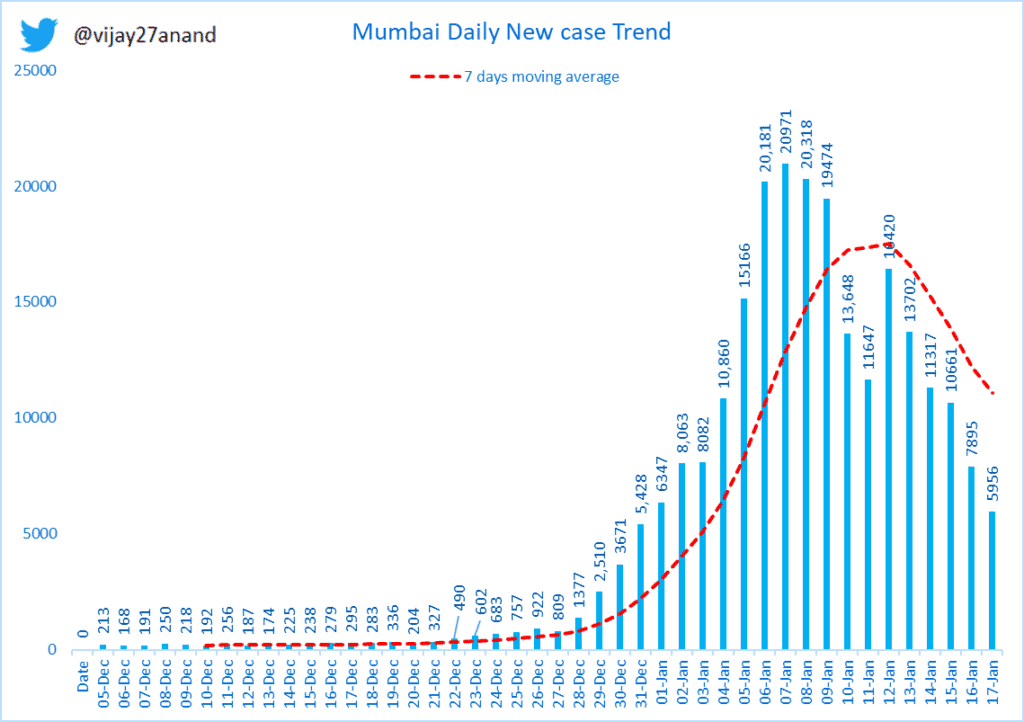

Mumbai’s third wave of COVID-19 began on December 21st, about a month after the World Health Organisation (WHO) labelled the highly infectious Omicron strain a “variant of concern.” It took 15 days for cases to reach an all-time high, topping 20,000 daily infections from January 6th to 8th. For comparison, the second wave peaked at 11,206.

The number of cases then began to reduce, gradually dropping to 11,647 on January 11th. Still fluctuating by a few thousands, the number currently stands at 5,956 with 479 hospitalisations.

However, this is accompanied by a reduction of over 10,000 in RT-PCR test numbers, and inversely, a 700% increase in the sale of self-test kits, of which, many results go unreported. These have raised questions about the suspected peak of the third wave.

“According to the WHO, the peak would come and go fast but others have said it will go on till February,” says Dr Sachin Pattiwar. Analysis by the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) placed the peak between January 6th and 13th, a prediction true till now.

Is a shortage of ICU beds possible in the future?

As of January 17th, 4,601 normal and 1,027 ICU beds were occupied. The burden on ICUs continues to be higher in private hospitals, which are 44% filled, compared to 24% in public hospitals.

“Around 90% of the cases are asymptomatic, and very few require oxygen or ICU beds,” says Suresh Kakani, additional municipal commissioner. Several war rooms concurred with this account, saying the demand for ICU and oxygen beds has been near to none.

“Delta was spread out over a much longer period. Here, the peak is really big because it’s spread out over a short period,” cautions Dr Lancelot. “Even if the health of 1% of all the high risk individuals deteriorate, it will significantly overwhelm the system.”

Compared to the second wave caused by Delta, the TIFR analysis pegged a drop in hospitalisations by 30-50%. This they attribute to the severity of Omicron, which is twice as infectious as Delta, but roughly 20% less likely to cause symptoms.

Vaccinations and previous reinfections also lower hospitalisations. This is reduced by 70% in those that are doubly vaccinated – 80% of adults in Mumbai – and previously infected.

“With every passing day, the situation is getting a little more reassuring,” says Dr Lancelot. “People who got infected 10 days ago, if they were going to, should have begun to deteriorate. But it doesn’t look like that’s happening.”

TIFR’s analysis took the maximum hospitalisations in the second wave to be 18,000. By this standard, the present 23,958 bed capacity across Dedicated Covid Hospitals (DCH) and Dedicated Covid Health Centres (DCHC) should tide this wave over. With the added support of CC2 facilities for mild and symptomatic patients, the current medical infrastructure is equipped to handle over 3,800 patients.