This article is supported by SVP Cities of India Fellowship |

When 78-year-old Shyamala (name changed) had a heart attack in the middle of the night, there was no one around to help. Shyamala was widowed, and had no children. “She was wailing from pain all night, but no one heard her. At around 5 am, neighbours came over, and Shyamala had to crawl up to the door to open it,” says Shyamala’s former neighbour G Ramachandra.

Shyamala’s condition was critical, and the neighbours took her to a hospital where she was operated on. But afterwards, Shyamala was worried of living alone again. She has since been staying at the Nightingales Elders Enrichment Centre (NEEC) in Malleswaram. NEEC offers living facility for elders who are relatively healthy; it’s is also a day centre for seniors to get together and do activities. The elders who live here get meals, and the help of assistants for daily activities like bathing.

Shyamala’s case is one among that of thousands of elderly in the city who have chronic health issues, but have difficulty getting care. While Shyamala was able to afford the cost of living at NEEC – Rs 900 per day – this would be unthinkable for the majority of elderly who are on their own.

The population of elderly in India has been rising steeply due to improved life expectancy, but there are no systems to deal with their needs. As per the 2011 Census, 8.6% of India’s population – 104 million people – are senior citizens, i.e., those above the age of 60. Of them, 11 million are aged above 80 years.

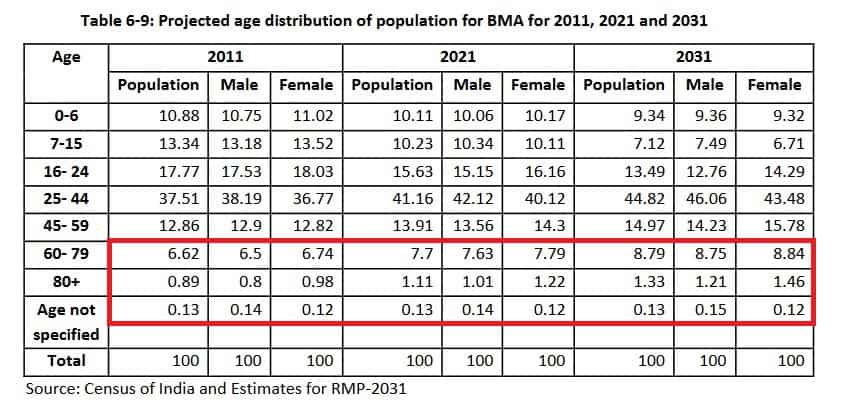

Census data compiled in the draft of Revised Master Plan – 2031 shows that population of people above 60 in Bengaluru has been on the rise.

No income, waning health

The elderly are mostly affected by chronic illnesses like diabetes, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, which require continuing medication and care. A recent study showed that around 18% of elderly men and 26% of elderly women in India have disability because of chronic diseases. They have difficulty or inability doing daily activities of walking, toileting and dressing. Disability was most prevalent among the elderly who weren’t currently married, those aged above 80 years, and those with low income and education. The study was based on data from the India Human Development Survey, 2011-12.

The survey implies that many seniors need the support of their family members just to go to a healthcare facility. Financial dependence is also an issue. N Murthy Rao, Vice President of the Federation of Senior Citizens Forum of Karnataka, says, “Very few seniors get pension from a former government job. Seniors aged above 70 years have restrictions in getting health insurance too. Only a small percentage have it, mostly by being covered in the family insurance plan of their child.” While insurance premiums generally increase with age, it has become even more expensive for the elderly in recent years.

Karnataka government’s Sandhya Suraksha scheme gives old age pension of only Rs 600 per month for disadvantaged elderly. The city’s destitute are unable to afford continuing medication with this amount, says Rekha Murthy, Karnataka Head of the NGO HelpAge India, that supplies free medicines to the elderly in the city’s slums. In this year’s budget speech, Chief Minister H D Kumaraswamy announced that the pension would be hiked to Rs 1000 starting November.

Elderly prone to abuse, neglect

Seniors have to depend on their children for healthcare, but many face abuse from children themselves. A 2018 survey by HelpAge India among 218 elderly Bengalurians found that a quarter of them had faced abuse at home. Of those who faced abuse, 73% said they had faced disrespect, 52% had faced neglect, and a small percentage experienced verbal, physical or economic abuse. The survey was held among mostly the “young-old” seniors, aged 60-69 years. The reasons for abuse were that the children wanted to live independently, didn’t like the elder person’s way of living, financial issues etc.

Of the seniors who faced abuse, only one-fifth had confided about the issue to a relative or friend. Hardly anyone had reported the issue to the police or an association. Most elders didn’t know how to deal with the issue or wanted to keep the family matter confidential.

Data from the city’s Elder Helpline 1090 also shows that many elderly face abuse from their family members. In 2017-18, the helpline got over 15,500 calls. The caller usually registers a complaint only if his issue is not resolved by other means like conciliation, counselling etc. There were 468 written complaints in 2017-18, of which half were about being harassed or cheated by one’s own family members. This includes cases where children don’t give maintenance to parents even while living with them.

Gurmeet Randhawa, Managing Trustee of Karunashraya, a Trust that gives free palliative care to terminally ill cancer patients in the city, says that they do get many elderly in-patients because the family lacks the time and ability to provide care.

“With the transition to the nuclear families, the elderly lack a support system. Unlike earlier, family members also have lesser attachment with the elderly person. But there are also cases where the family goes out of their way to care for the elder,” he says. There are also extreme cases of abandonment – every year, the Trust gets 10-12 in-patients who were abandoned by their families in hospitals. Overall, Karunashraya provides in-patient care to about 1400 people a year, and home-based care to 70-80 patients at any time.

Support systems lacking

Randhawa says that senior citizens who live just with their spouse face more challenges accessing healthcare. “The logistics of going to a healthcare facility, one spouse having to manage the house while also caring for the unwell spouse, are all challenges. This section of elderly population is increasing as more youth are going abroad for jobs or living separately,” he says.

Also, like Shyamala, there are some 15 million elders in India who live alone, three-fourths of them women, as per 2011 Census.

Even in cases where children care well for their elderly parents, there are challenges. In case of chronic illnesses, especially those like dementia and advanced cancer where the patient’s condition only deteriorates further, the caregiver suffers tremendous physical and emotional strain. Carers, who are most often women, also end up quitting jobs or shifting to part-time jobs.

As per the Dementia India Report 2010, the average cost of caring for a person with dementia was Rs 1.4 lakh annually, as of 2010. The cost would be much higher now. Carers tend to develop depressive disorders and physical ailments as well. A study among 179 carers of people with dementia, cited in the report, had found that 60% of the carers had developed mental health issues.

All these point to a high need for government support in elder care, even in cases where children do care for ageing parents. In many developed countries, there is high investment in elder care. UK government, for example, facilitates home care providers whose services can range from help with domestic work to full-time nursing care. These services – either paid for by the family or funded by the local council – ensure that the elderly person stays comfortable in their familiar home environment, and that the carer gets support. There are also provisions for free equipments, and free nursing care in a care home for those who qualify.

In India, there are no such services yet. During an acute illness, the elderly person may be admitted to a hospital, but there are no facilities for long-term care after discharge. The central government’s National Institute for Social Defense (NISD) currently has programmes to train home nurses for elder care. But the number of people trained are minuscule compared to the demand. Hence, most home nurses currently come from the informal/unorganised sector, with little skills and training.

The cost of employing a full-time home nurse is also unaffordable for many families. Except a few organisations like Karunashraya and Nightingales Medical Trust, there are hardly any care homes as well in Bengaluru.

Hospitals lack geriatric wings

Even though healthcare needs increase with age, there is little focus on geriatric medicine – the specialty that focuses on preventing and treating diseases in the elderly. Currently, only a handful of corporate hospitals in Bengaluru, like Manipal and Apollo, have dedicated geriatric wings; the majority of private and government hospitals don’t.

Dr Anoop Amarnath, Chairman of Geriatric Medicine at Manipal Hospitals, says that the lack of trained geriatricians is the main reason for the severe shortage of geriatric facilities. “There are only a couple of medical colleges in the country that offer an MD in geriatrics. In MBBS also, there’s no separate course on geriatrics; there are only a few chapters that mention it,” says Dr Amarnath. In contrast, in western countries, geriatrics is part of basic medical training, and there are postgraduate courses – like geriatric nephrology – that offer specialisation within geriatrics.

Dr Amarnath says knowledge of geriatric medicine is important for doctors, since it affects outcomes for the patient. Diagnosis and treatment varies for the elderly. “Manifestation of a disease may be different in the elderly. For eg., a young person with urinary infection will have only regular symptoms, but an elderly person may develop delirium or unconsciousness.”

Also, in case of the elderly, multiple organs are affected, and the treatment can’t be as aggressive as in the case of youth. “In the elderly, multiple organs are usually involved, with multiple issues. The treatment that’s good for one organ need not be good for another. Also, aggressive treatment may not be appropriate – a young person with diabetes will be required to control his sugar levels tightly, but it’s not to be treated the same way in an elderly person,” says Dr Amarnath, who was part of the Karnataka Knowledge Commission team that submitted recommendations on elder care to the state government.

Indian government does have a National Programme for the Health Care of Elderly (NPHCE), launched in 2010. But the execution of this programme has lagged severely.

Under the project, 20 medical colleges in the country would be developed as Regional Geriatric Centres, and Bangalore Medical College is one of them. Dr Satish H S, Director cum Dean at the medical college, says that geriatric Out Patient Department (OPD) is already functional here, and that a 30-bedded geriatric ward will start functioning in a couple of months.

However, NPHCE has not been implemented in Bangalore district. Under NPHCE, there will be separate geriatric wards and OPDs in district hospitals; PHCs and CHCs will have geriatric clinics. Also, health workers at sub-centres will visit the elderly at their home and arrange supportive devices. The idea is to provide healthcare to all sections of the elderly, focusing on prevention and on management of chronic diseases. So far, only a few districts in Karnataka have piloted NPHCE.

For now, the government machinery is almost nonexistent in supporting healthcare needs of the elderly.

In the absence of government support, more private players are entering the senior healthcare scene. In part 2 of this series, we explore this segment.

This article is supported by SVP Cities of India Fellowship.

|