Kumar*, a food delivery gig worker rode back home after midnight on his scooter a few weeks back. Suddenly, a few cops stopped him on the way, captured his photo and then let him go. “Why are you taking my photo? I have my driving license and other documents, and I am also wearing my helmet,” he asked them, flabbergasted and confused. But they did not respond. Little did he know that the Chennai police might have used their facial recognition technology (FRT) to see if his photo matched that of a criminal in their database.

This has been one among many instances of profiling that have been taking place in Chennai recently.

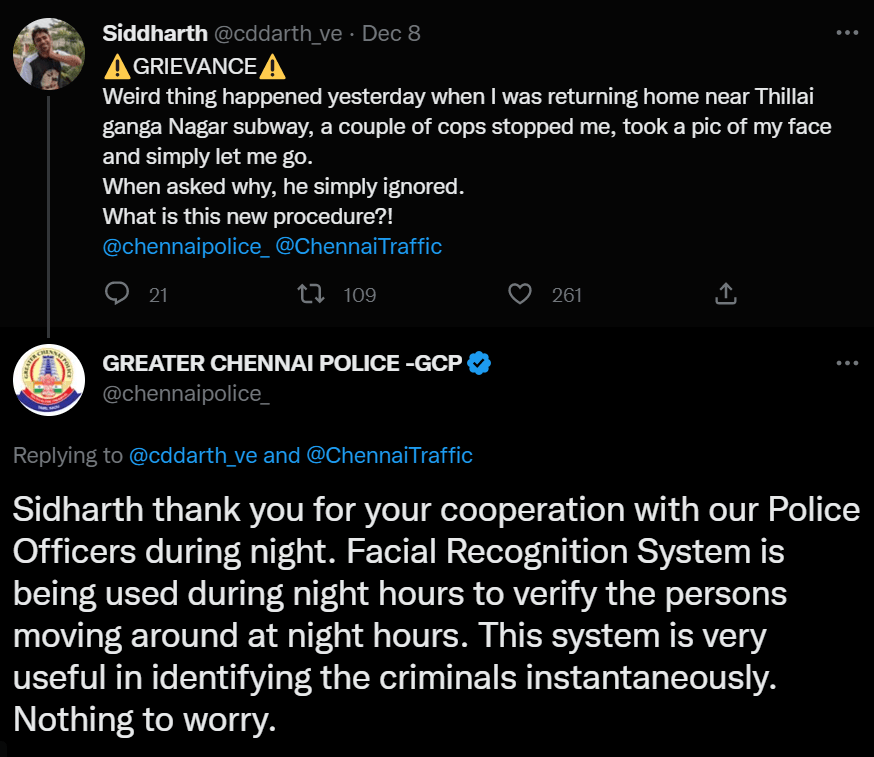

Another person whose picture was captured took to social media to raise the issue, eliciting what many deemed a less than satisfactory response from the Chennai Police.

Can the Chennai Police stop and take a photo of anyone? What does the law say and why do they do it? We take a deeper look into the issue.

Read more: Pulled up by traffic police? Know your responsibilities and rights!

What is FRT? How does it work?

Sruthi Kalyani, a tech research scholar at the Jawaharlal Nehru University explains how FRTs work generally. “It [FRT] detects an image of a human face. Then, it adjusts the face, to enable comparison. After that, it takes the unique features from the face to form a code [digital signature]. This code is matched with other faces in an existing database.”

If your face is run through FRT, it will take some data points from your face, and will create a digital signature using algorithms. Then, the technology will try to match your digital signature with those in an existing database.

“It is different from the face recognition software which is used to unlock a smartphone. Facial recognition technology used by the Chennai police compares one face with many faces. But, unlocking the phone needs comparing of a face against the same one,” she continues.

In other words, the police use 1:many identification, while a smartphone uses 1:1 identification.

Facial recognition technology used in Chennai by the police

In Tamil Nadu, there are seven FRT systems installed, with two being used at the moment, and the rest are under procurement and tenders. The Tamil Nadu Police in Chennai and the Tamil Nadu e-Governance Agency are using facial recognition technology for surveillance and identity authentication respectively, according to Panoptic, a project by the Internet Freedom Foundation.

In October 2021, the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister, MK Stalin launched a face recognition software with more than 5.3 lakh images of criminals. This tool was meant to help the police in nabbing criminals.

This FRT is in the form of a mobile application. A policeman can take a photo of someone’s face and compare it with a database of images from the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and System. It is supposed to help them immediately figure out the criminal history of the person.

“Facial recognition technology is used on accused, suspects and police verification cases in Chennai,” says Vinit Dev Wankhede, Additional Director-General of Police and Head of the State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB). “We use it selectively during night patrols. Every day, 10-100 matches occur. Plus, there are also many success stories where it has helped us nab criminals.”

“It eases solving cases and crime prevention,” he adds. For instance, let us imagine a criminal from Madurai has escaped to Chennai. A Chennai cop may not be familiar with Madurai criminals. But facial recognition technology would help the Chennai police identify criminals from other places immediately.

“The current FRT system has been developed by the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing [C-DAC],” says Vinit. C-DAC is a Research and Development organisation of the Union Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology.

“This app is less pervasive than FRT-integrated-CCTVs. And only field officers use FRT,” he continues.

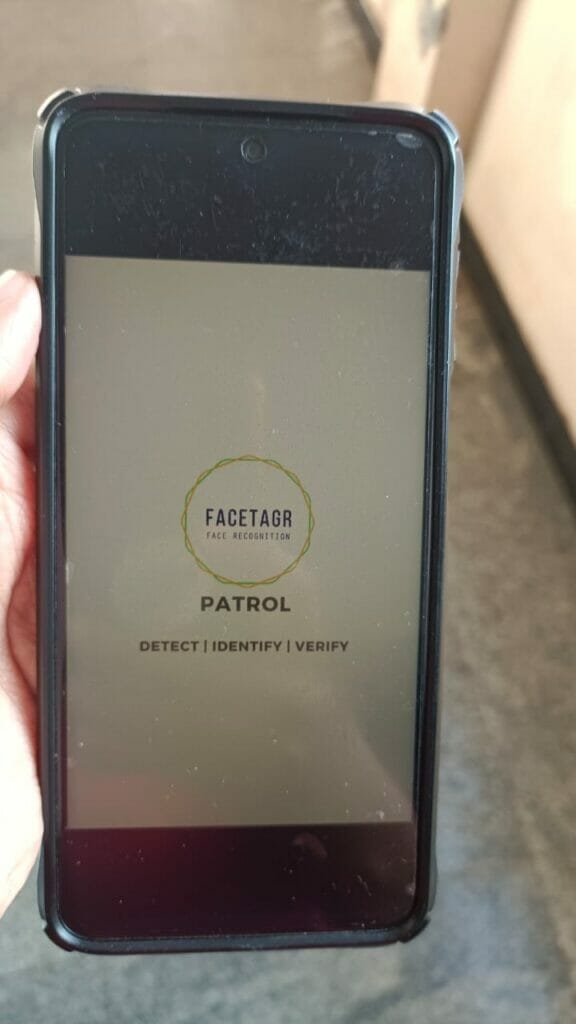

Previously, since 2017, the city cops were using real-time CCTV footage to compare with the criminal database developed by FaceTagr, a private AI company based in Chennai. Subsequently, the cops also started using its facial recognition app.

Tamil Nadu Director-General of Police Sylendra Babu points out that the use of FRT is not limited to identifying criminals. “FRT is also used to identify missing people and unidentified bodies. The FRT is linked with a cop’s Kaval Udhavi application in his or her phone,” he says.

Read more: Explainer: How to access free legal aid in Chennai

Do legal provisions support the Chennai police in using facial recognition technology?

The Chennai police use the following legal basis to employ FRT.

- Section 21 of the Tamil Nadu District Police Act 1859: A police officer must try to prevent all crimes, and apprehend disorderly and suspicious characters, among other duties.

- Section 41(1) The Code Of Criminal Procedure, 1973: Police may arrest a person without a warrant when the former suspects that the person has done an offence, among other reasons.

But there are grey areas and concerns.

“There is no FRT-specific regulatory framework in India, which directs the government in decision-making,” says Sruthi.

However, digital technologies are currently governed by the Information Technology Act, 2000. Section 43A of the Act notes that if private parties misuse personal data, then they are liable to pay damages to the person whose data was misused.

Also, FRT can violate the Right to Privacy. This right is a part of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, as per a Supreme Court ruling in the case of Justice K.S.Puttaswamy (Retd) vs Union Of India in 2017. If there is no legal framework for the use of a technology like FRT, then it is a violation of Article 21.

“Real-time FRT used for law enforcement and surveillance is mostly consentless participation. The citizens don’t even know they are data,” says Sruthi. In other words, forced biometric recording is not legal.

“These are stop-and-scan searches. Cops stop people and scan biometrics. Biometrics include iris, photos or fingerprints. These happen across India. Police would claim that this is part of Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act, 2022. But the criminal identification act does not say that they can stop and scan everyone,” says Srinivas Kodali, an independent researcher on internet movements.

Concerns around use of FRT

“I don’t know if the police are taking my photo using the FRT app, or storing it in their gallery for some other purpose,” shares Praveen, a resident of Thoraipakkam who also experienced FRT-based policing in Chennai. “I also do not know how and where my photo could be used.”

When we flagged this concern and pointed out that most people are not aware of the cops taking photos for facial recognition, and that this may cause apprehension and panic, SCRB head Vinit said that he will make sure that the cops orally inform people about FRT.

However, the SOP used by the police to use FRT is not in the public domain.

While the police claim not to store images of those being profiled thus, if the image matches and the person gets accused of an offence, then it could be stored in the database for 75 years, as per The Criminal Procedure (Identification) Act, 2022. However, if the person’s charges are cleared, their data could be removed before the stipulated duration.

Even though it is touted for its real-time identification of criminals, FRT is not fully foolproof. NITI Aayog lists the risks associated with FRT. A few of them are given below.

- A person’s facial expression, pose or even lighting of an image can make the FRT misjudge digital signatures.

- It can cause bias in terms of gender and race. “For instance, there are ten samples in a database and seven of them are dark-coloured with male features. Then, the algorithm can misjudge people with similar facial features, putting them on the radar,” says Sruthi.

- There can be technical glitches in the software which can misidentify criminals.

It can also be used to target some individuals, say the experts.

“During the CAA protests in early 2021, a police officer was seen recording protestors waiting for their bus. Because of an incident in Delhi where FRT was used to identify protestors, there were fears that the police officer in Chennai was doing the same even though it was never proven. At that time, some police stations in Chennai were using Facetagr,” notes Asvatha Babu, a PhD candidate studying facial recognition in Chennai.

Srinivas says that FRT could deter people from assembling, dissenting and peacefully protesting. “Privacy is just one aspect. But it could affect a citizen’s freedom of speech,” he adds.

Can people take a stand?

Telangana High Court has issued a notice to the state government on a PIL by an activist, which challenges and questions the usage of FRT.

But there is not much leeway to deal with FRT legally. Under Section 42 of the Criminal Procedure Code, anyone who does not provide identifying information to the police when accused by them of any wrongdoing may be arrested.

“The police’s justification for the use of this technology is that it makes it easier for them to identify people. I don’t see how anyone could legally refuse to participate in this surveillance,” remarks Asvatha, adding that the power asymmetry between the police and the public is large, and some may think that it would be safe to comply.

But it is not a bleak situation yet. “Hopefully it encourages more people to come forward and legally challenge the use of FRT by cops in Chennai. My fear is that the judiciary will side with law enforcement, which will encourage a more pervasive and varied use of FRS by cops,” she adds.

Recent days have seen Members of Parliament Writer Ravikumar and Karthi Chidambaram write to the Chennai Police questioning their use of FRT on citizens.

It is important for us civilians to cooperate with the police to prevent and solve crimes. But the means do not justify the ends.

It leaves us with the question: “Can we let our rights be steamrolled for the greater good?”

*name changed on request

Excellent article and very exhaustive information about FRT