Bengaluru is the second city in India, after Mumbai, to have Dry Waste Collection Centres (DWCCs). Since 2012, BBMP has been setting up these centres in the city. While 198 DWCCs have been sanctioned for Bengaluru, 166 are functional, with capacity ranging from 0.5 to 4.5 tons a day.

DWCCs are operated with the participation of waste-pickers and informal waste collectors. Thirty three DWCCs that are operated by waste-pickers, are supported by the NGO Hasiru Dala. These 33 DWCCs have special orders to engage in the bi-weekly collection of dry waste directly.

DWCCs were set up to provide decentralised dry waste aggregation and sorting facilities within neighbourhoods. The initiative to install DWCCs and include waste-pickers is laudable. DWCCs receive dry waste including high-value recyclables, low/no value materials like multi-layered plastic, and rejects including bedding, shoes, clothes.

Since Dry Waste Collection Operators started door-to-door waste collection, the proportion of low-value waste has increased to around 82 percent of the total dry waste collected. This poses important questions on the present design of DWCCs.

The design of most of DWCCs was developed based on a BBMP circular of 15th February 2013, and based on an older understanding of dry waste management. To systematically understand the gaps and challenges in DWCC design, a group of four students from the University of Washington, along with the staff of Hasiru Dala, probed the condition of 16 DWCCs this February-March.

They documented the capacity, operational issues and structural conditions of the centres. The survey looked into the design, composition of waste, along with the number of people working in the DWCCs, their everyday lives and their role in the city’s solid waste management. Most DWCCs were found to be haphazardly-installed four-walled structures with tin or cement roofs. They lie in structural disrepair, having functioned above capacity.

Common design challenges in DWCCs

- Lighting and ventilation: Being makeshift structures, DWCCs are poorly lit and ventilated, making it unhealthy for workers. Many DWCCs depend on electricity for both light and ventilation, but electricity is unreliable due to frequent power cuts.

- Wiring left open: Due to makeshift cabling, poor maintenance, and heat due to the tin roofs, electrical wires in DWCCs have become a fire hazard.

- Water and sanitation: In most DWCCs surveyed, there were no toilets. Among the ones that had toilets, the plumbing was non-functional or was not connected to sewage lines.

- Cleanliness: When households don’t segregate their waste, mixed and reject waste end up at DWCCs and lie there until it is picked up or sent away. There is no proper stocking of reject waste.

- Construction issues: Improper construction know-how and use of substandard materials for quick and cheap construction, have resulted in structurally unsound buildings. Add to that the age and lack of repairs/upgrades to DWCCs, a lot of them are falling apart. In many DWCCs, parts of the floors and even the walls have started to cave in. The foundations in many have been badly damaged from rodents digging underneath. In one case the, DWCC was built over a drain, and could collapse any time.

Inside a DWCC. Pic: wastenarratives.com

- Roof leakage: During rains, the leakage through roofs, wall cracks and windows damage high-value recyclables like newspapers, magazines and cardboard boxes. Temporary fixes each year stress the existing structure, damaging it further. Such fixes costs the operators, but does not offer a long-term solution.

- Property damage: Land outside the building, where loading and unloading is done, is surfaced only in a few DWCCs. Over the years, even these have broken under the load of moving goods. This has led to uneven settling of the land, and unsafe loading/unloading. The water-logging that happens in these fissures also leads to poor working conditions.

Most DWCCs have poor infrastructure. Pic: wastenarratives.com

- Pests, rodents, and animals: Many DWCCs have rats and insects running through the cracks in the floors and walls. In a few DWCCs where the compound wall has been damaged, there have been cases of dog-bites from dogs squatting on the premises. Snakes have also been observed on rainy days.

- Working conditions: Tin sheds heat up during the day and create difficult working conditions, especially in unventilated spaces. Rainy days are especially hard to work in because recyclables get damp and dirty, and paper ends up losing value. Also, mattresses dumped at DWCCs soak up water and get mouldy, making their disposal challenging.

- Space constraints: Many DWCCs have been allotted smaller space than is required. Since the majority of waste that comes from door-to-door dry waste collection are non-recyclables and rejects, the centre ends up being overrun with bags of multi-layered plastics and mattresses.

Many DWCCs have space constraints. Pic: wastenarratives.com

Remedial design suggestions to better DWCCs

Hasiru Dala has experimented with a few design changes in the DWCC of Marapana Palya (ward number 44), which has shown results both in operations and in the lives of workers.

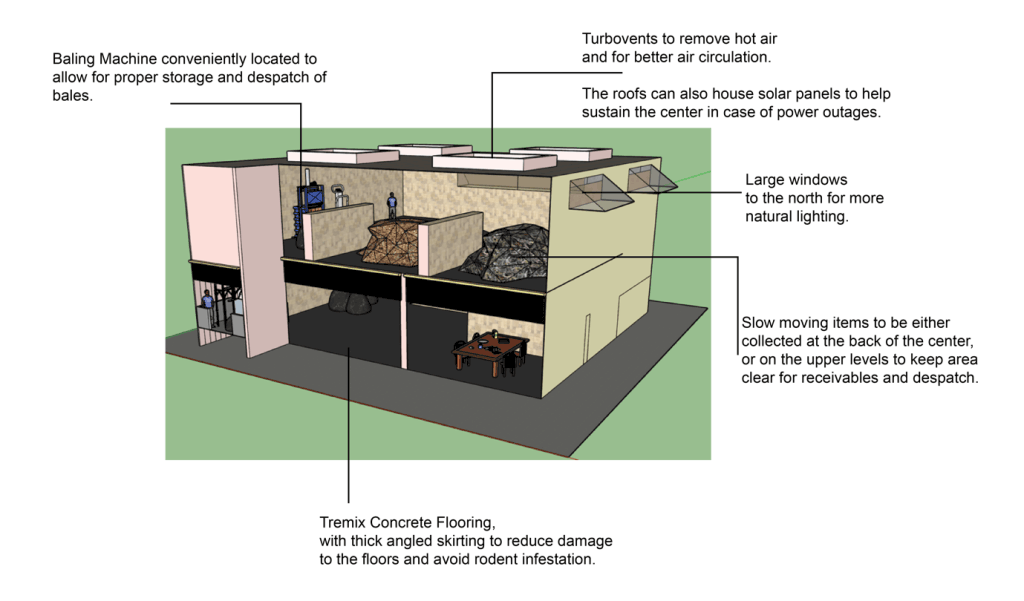

Based on observations from our study, some suggestions are shared below, to help build more future-ready DWCCs. They take into consideration growth, working conditions, different types of waste received, and operational necessities.

- Organise the flow of waste

- Unsorted waste should be stored at the entrance of DWCC, and plastic towards the end. Paper can be stored in the front so that it can be saved in case of a fire. Frequently saleable materials should also be stored close to the door.

- No electrical wires in the stocking area of plastics and other inflammable materials.

- A conveyor belt is essential to improve the productivity of workers.

- Frequently saleable materials should be stored closer to the door, whereas rarely sold items like metals should be moved to the upper or mezzanine floor. Minor electronic waste, which are low in weight and take time to collect and transport, should also go on the upper floor. Non-recyclables storage typically needs a large space.

- There should be space around the baling machine to walk and move around (Baling machine is used to compress waste into bundles).

- There should be reject waste bins that can be closed and are difficult for rodents to reach.

Proposed changes to DWCC design. Credit: wastenarratives.com

- Provide appropriate facilities

- Office space, and changing rooms with lockers for workers

- Toilets with a sanitation pipe connection. Overhead water tank for drinking and sanitation use

- Appropriate space for a fire extinguisher and weighing machine

- Record keeping – both computer and storage space

- Display of boards that depict processes, types of sorted waste etc

- Display of rate card of materials

- Improve infrastructure

- Prevent radiant heat: To save time during construction, many DWCCs were built with tin or cement sheets. The temperatures inside them peak during high sun, to unworkable conditions. To prevent this, insulating materials like thermocol should be used where suitable. Large windows should be provided on the north side, along with openings to facilitate cross-ventilation.

- Soil tests: Soil tests should be made mandatory before construction. Structural design must take into account the effect of seepage into land, and also the potential heavy loads on driveways.

- High ceiling: Sufficient space will improve working conditions in DWCCs during summers. It will also allow expansion of the centres’ capacity later. The upper deck can be used as office space, and to store slow-moving lightweight items.

- Roof lighting: Transparent panels will help light the building. Turbo vents can help ventilate buildings without power. This will help save costs and minimise health issues, especially respiratory issues, from working in dark and closed-off conditions.

- Robust materials: With use and neglect, the doors and windows of DWCCs are permanently closed off or open, the glass or infill panels are broken, and they offer no protection from the elements. The material for doors and windows should be lightweight but robust, that will survive harsh use in high-traffic areas. Ferrocement is a good option here, since it is hardy and waterproof, and will last for years with the right detailing.

- Tremix flooring (VDF): This is an industrial monolithic flooring, designed for high-traffic areas where the flooring tends to crack. This will also help fight the dislocation of the structure in cases where the soil is wet or loose. The higher cost of Tremix flooring will be compensated by the reduced repair costs through the building’s life span.

- Skirting: To avoid rodents burrowing and entering from the corners of the building, appropriate skirting (a strip covering the corner) should be provided.

- Appropriate bin for tube lights

- Annual audit: The condition of DWCCs should be investigated once a year, to fix problems early on and avoid major repairs. The facilities in the centres need more frequent checks and repairs.

-

- Value-added measures

- CCTV camera

- Security room styled like a fishing bowl, that will allow easy supervision

- Garden to keep smells at check, with specific spaces for planting fragrant varieties like Parijat/Nyctanthes, jasmine, tube rose etc

- Mural outside the centre that depicts its functioning and the people who run it

- Small composting unit to discard wet waste that has come with the dry waste, and a storage drum for dry leaves

- Regular pest control measures with either chemical or electronic devices

- Rainwater harvesting for surface runoff

- Solar panel for light, water pump and simple baler

[This article is based on research by Anjanee Patel, Ambrosie, Jaspreet Singh, Indha Mahoor, Nalini Shekar, Karthik Natarajan, Vishwanath C and Xiao-Dong Liu. It first appeared in the website wastenarratives.com, and has been republished with minimal edits.]