“Earlier, we would wash clothes by the riverside. But later we dug up bore wells in all dhobi ghats, which have become our main source of water,” says Mahalingayya, president of Karnataka Rajya Madikatte Ghataka that oversees the functioning of dhobi ghats across Karnataka.

In Bengaluru, each dhobi ghat has at least two borewells. However, water scarcity is still an issue. The solution is using recycled water. But the cost and maintenance of water treatment plants are of primary concern.

Water usage in dhobi ghats

Each dhobi ghat uses varying quantities of water on a daily basis. The average can go up to one lakh liters of water, as per Keshava, president of Bengaluru Dhobi Ghats Association. In some places, like Vyalikaval dhobi ghat, they order water tanks from BBMP during water scarcity. In extreme cases, in places like Srinagar Dhobi Ghat, all work stops until the borewells are filled up.

Srinagar Dhobi Ghat, which has 180 members, was one of the three dhobi ghats in which a recycling plant was installed in 2018 by JK Nanosolutions, a nanotechnology-based startup company in Bengaluru. “When the plant was functioning, we were able to recycle about 90% of washed water that helped us deal with water scarcity,” says M. Narayana, General Secretary at Srinagar Dhobi Ghat.

Why are there no water treatment plants, then?

In 2018, JK Nanosolutions used its grant money, awarded to them by the Design Impact Award by Tata Trust and Titan Ltd (2018), to build water treatment plants at three dhobi ghats, located in Rajajinagar, Srinagar and Vyalikaval. “We were approached by the then MLA of Malleshwaram to set up a water treatment plant at Vyalikaval, where there already was an effluent treatment plant (ETP) set up under the MLA’s fund, but was not in a functioning state,” says Kiruba Daniel, founder of JK Nanosolutions. Having conducted a pilot study and research at the three dhobi ghats, the company set up the machinery at the three dhobi ghats and promised to maintain it for two years with the grant money.

In Rajajinagar and Srinagar, the plant functioned well for about three years, after which the company claims that the members stopped taking solutions from the company without any notice, while the dhobis claim that they stopped receiving solutions from the company owing to a fund crunch.

When the plant was installed in Vyalikaval, the members raised concerns about the foul smell and the pale colour of the recycled water, which was fixed by the company. “After fixing the issue at Vyalikaval, the plants in all three dhobi ghats were functioning well. Rajajinagar and Srinagar showed better results since they were facing water scarcity and the recycled water helped them with their situation. But due to the abundance of water at Vyalikaval, the members did not take enough interest to engage with the plant,” says Kiruba.

Since dhobi ghats use heavy chemical detergents for clothes, the total dissolved solids (TDS) crosses 1,000 parts per million (PPM), which is tagged as unsafe as per EPA Secondary Drinking Water Regulations.

Read more: Bengaluru’s dhobi ghats keep their legacy afloat

“We set up the plants and ensured that they were in the ownership of the dhobi ghat associations. However, due to lack of awareness about the importance of recycling water, the plants are not being used efficiently. We have tried every possible means to stay in touch with them for solutions, regarding any repairs or guidance, but they have not taken enough interest in getting back to us,” says Kiruba.

After the installation of the water treatment plants, maintenance is also important. The dhobis are already paying for maintenance charges of the dhobi ghat, the washing machines and other machinery installed by the government, in addition to electricity and water charges. They are, therefore, financially struggling with extra charges for the recycling plants.

So, where does the water go?

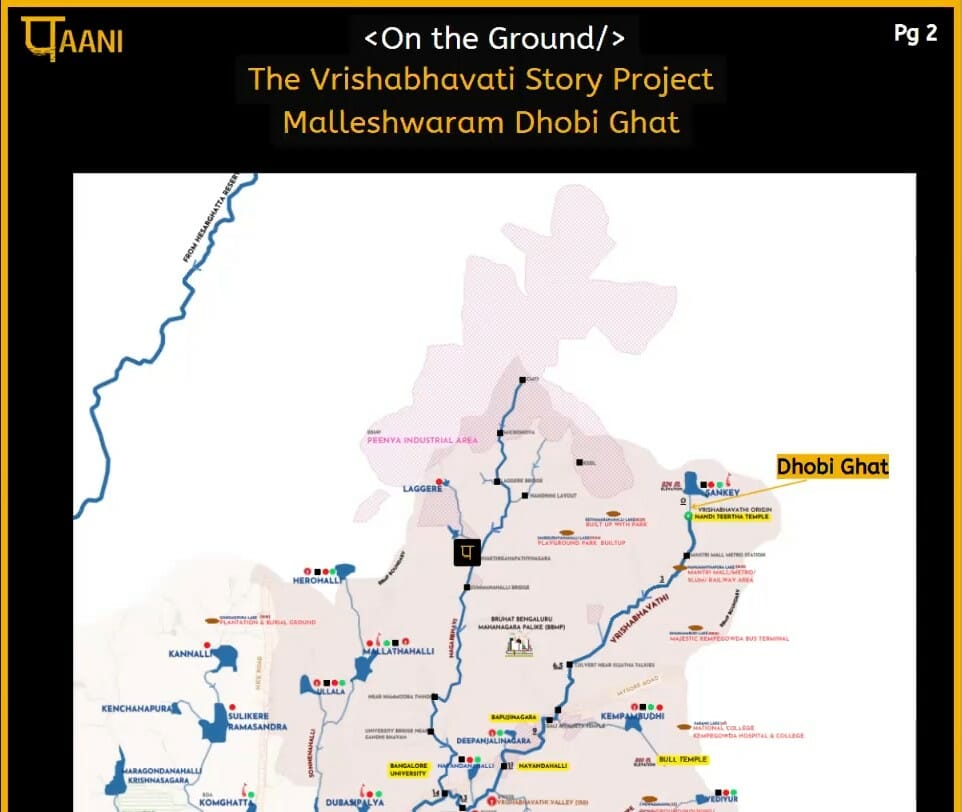

“The storm water drain passes through the dhobi ghat, and all the effluents from there go through these pipes and reach the Vrishabhavathi River,” says Khushbu Birawat, researcher and curator at Paani.Earth who is currently researching the Vyalikaval Dhobi Ghat. The detergents used by the dhobis to remove stains are corrosive and are high in phosphate, which is one of the leading causes for frothing of lakes. “Many NGOs and corporates have tried to enable effluent treatment plants, but they are all defunct. One of the main reasons is the cost of maintenance, which is not affordable for dhobi ghats,” says Nirmala Gowda, founder and curator Paani.Earth.

Who is accountable?

When Citizen Matters asked Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) if they are in-charge of the environmental issues at dhobi ghats, they denied responsibility and instead pointed fingers at Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB). A statement from BWSSB is awaited and will be updated, in this story, when received.

“BWSSB deals only with sewerage lines and the sewage that is released from households and other places is biological and needs biological treatment. However, the effluents generated at dhobi ghats are not biological and require different treatment altogether. It hence cannot be connected to the BWSSB lines,” says Nirmala.

The research undertaken by Paani.Earth is only on Vyalikaval Dhobi Ghat, but it gives an insight into how much effluent water is being released from dhobi ghats.

Multiple parties should come together for a solution

“We are requesting the government to help install a water treatment plant in our ghat so that we can use recycled water more effectively,” says Ramesh Raj, president of Mahalakshmi Dhobi Ghat (next to Iskon Temple)

“The rich are externalising problems through the poor. While hospitals and hotels charge higher from consumers, they bargain with dhobi ghats where they give their clothes for washing. Pollution is a problem of the commons. It has to be stopped and we should all take responsibility towards tackling it,” says Nirmala. “This should go beyond a private startup initiative, and either National Green Tribunal (NGT) or KSPCB should take the initiative to install water treatment plants at dhobi ghats,” says Kiruba.

“Cleaning wastewater is not an immediate need, as it is not drinking water that is polluted, rather mere wastewater that people want to dispose of easily,” says Nirmala.

Corporation and contribution from all stakeholders

For on-site treatment facilities to benefit both the dhobis and the environment, collaborative efforts from the government, citizens, and corporates can help. Here are a few suggestions:

- People who use dhobi services can take an active interest in the issues of dhobi ghats. They can support them by paying more for services. This could help in funding and maintaining water treatment facilities.

- Government agencies can implement policies, regulations, or financial support to enable the effective functioning of the on-site treatment facility. They can ensure proper waste management and environmental protection

- Corporates can also contribute to pollution control and sustainable development by initiating and supporting relevant projects

[In part one of this series, we looked at the livelihoods of dhobis in Bengaluru]