Everyday from 12 am to 3 pm, Mayank* works for Tokree, a grocery delivery app. He then switches to the ubiquitous black-and-orange Swiggy t-shirt, and from 3 pm to 12 am delivers food from restaurants to homes. “For every Tokree delivery, I get paid Rs 35. But with Swiggy, I only get a minimum of Rs 20 per trip,” he says.

Mayank is one of the 3+ lakh strong workforce in the country suffering the brunt of low wages and poor working conditions in the food delivery and e-commerce industries.

Unable to make ends meet, many of them are switching to better paying delivery gigs. “Evenings are peak hours for food delivery, which is when they switch to Zomato or Swiggy,” says Kiran Anand, treasurer of the Maharashtra App-based Transport Workers Union.

It wasn’t always this way. When Mayank started working for Swiggy in 2018, his base pay – the minimum amount received per delivery – was Rs 40. He is not sure how, but he was automatically locked out of his Swiggy ID, which made him rejoin in 2020 and forced him to start from scratch.

Although the number of orders have increased during and since the lockdowns, because of the reduced base pay, he is making less money than before. With Swiggy, he says, “Before the lockdown, I easily made Rs 600-700 a day. But now, I make close to Rs 400-500.”

Leveraging competitive wages

Other companies have been using the wide scale disillusionment among delivery partners with larger delivery apps such as Zomato and Swiggy to their advantage.

Tokree reached out to Mayank by accessing a database of Swiggy’s drivers, offering not only better pay, but incentives on bringing new customers on board. Shadowfax and Porter, multipurpose delivery service companies, have been targeting prospective drivers by offering a joining bonus and waiving off the onboarding fee.

Santosh, who has a morning shift delivering couriers for Shadowfax, admits to preferring it over Swiggy. The appeal is undoubtedly their higher pay; Shadowfax pays Rs 30 per grocery delivery, and Porter pays a rate of Rs 10 per km, with a 15% platform fee. Karan, working 12 hour days for Borzo (previously Wefast), manages to earn over Rs 4500 in a week, and finds the work a lot more comfortable than Swiggy.

“At least in e-commerce delivery jobs, drivers are guaranteed a certain pay per day and they don’t need to spend hours waiting for orders. They typically finish their deliveries in 4 hours and earn Rs 500,” says Kiran Anand.

Porter, Shadowfax and Borzo are not small companies. Each has over a million downloads on the Google Play Store. But they are inconsequential compared to Zomato and Swiggy’s 100 million+ downloads. And as their popularity increases, they too are primed to cut wages. Borzo has already done this once, Karan says.

Zomato, Porter, Borzo, Shadowfax and Tokree were contacted through email but declined to respond for the story. Swiggy responded with links to the blog posts which are included in the story.

“The companies are competing for workers and consumers, so they have to choose between who they want to attract and how much loss they’re able to take,” explains Vidhya Soundararajan, Assistant Professor of Economics at IIT Bombay.

Not a long term option

A survey by Praja Foundation done in January 2021, on the impact of Covid-19 in Mumbai, found that at least 66% of respondents either lost or took a hit to their earnings due to the pandemic. “Because of job losses in lockdown, many more drivers have joined [the delivery app space],” says Raza*.

This translates to fewer orders per delivery partner, and creates prime conditions for the reduction in earnings. Unemployment, consequently, compels them to work for lower pay. “Gig work has helped out a lot of people during the pandemic,” says Vidhya. “But because they don’t involve any skill building, there is no scope for progress. There is also the question of social security – how quickly they can get fired.”

Akshay*, a law student uninterested in online lectures, took to deliveries to earn for a vacation in Kashmir. But for many, this job is a temporary solution to the lack of jobs available.

Gourav has no choice but to make do with the Rs 25,000 per month (without accounting for petrol and other expenses) he earns through Swiggy, despite this being half of his pre-lockdown pay. Previously a relationship manager at a small bank, meeting targets of selling loans to MSMEs quickly became unviable due to the pandemic. He survived the lockdown on his savings, eventually resorting to working with Swiggy in February 2021.

“There has been an influx of workers from different fields, from engineers, share brokers to salesmen, but they won’t stay for long. They realise quickly that this job isn’t doable. Only the very poor and desperate stay,” says Kiran.

Read More: Employment worries multiply for recent graduates

The gig economy boom

India has seen a proliferation of food and other delivery apps in recent years. A crucial aspect about them is that their large fleet of delivery workers are not considered employees, but ‘delivery partners’ relieving them of all responsibility towards employee safety and benefits.

Anyone with a 2-wheeler (in some cases, a cycle too) can apply to become one through the respective ‘delivery partner’ mobile app. This is often framed as a steal, with flexible timings, frequent payouts, incentives and easy earnings. But, is it?

In practice, this has meant 12 hour work days without adequate payments for overtime, no holidays, provident funds or job security, according to a lot of delivery workers we spoke to.

This is in stark contrast with the Employee Benefits listed on Zomato’s website, including an in-office psychiatrist team, daycare facilities and period leave. By positioning them as independent contractors, these companies are not answerable to their largest workforce, who face the uncertainties of road travel, weather, and customers.

The pay and designations offered are a mandate; they can either take it, or leave it.

Unrewarding work

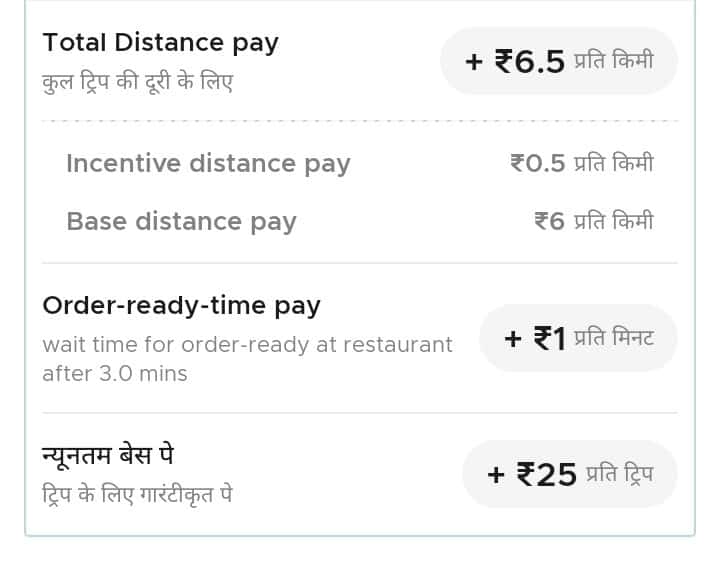

The companies offer prospects of earning above the base and distance pay, like a surge price during rains, dinner time, weekends, festivals and IPL matches.

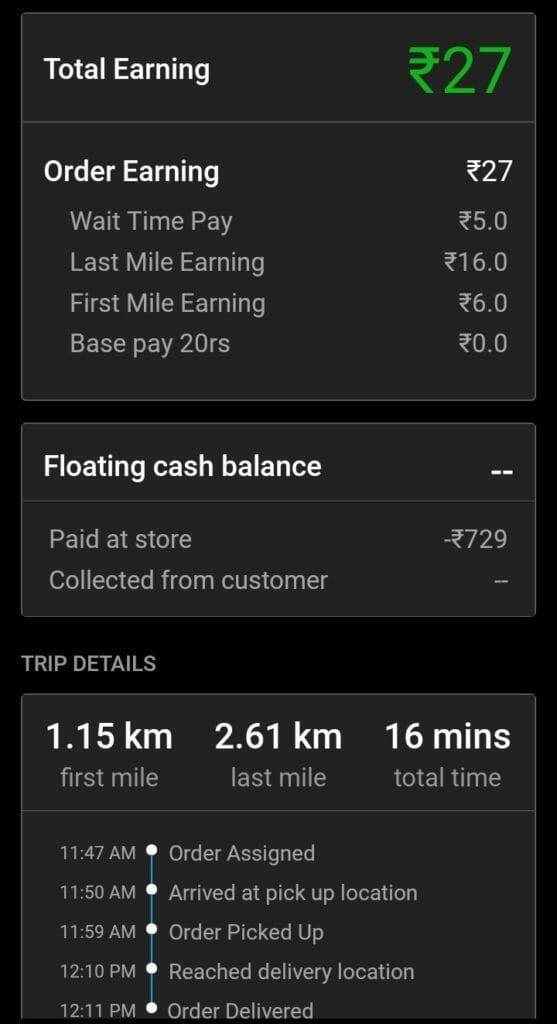

“I’m only doing this [delivering food] because of the surge pay. Otherwise I don’t think it is worth doing,” says Santosh, who switched from Swiggy to Zomato and is now back with Swiggy. By his calculations, if not for the rain surge and restaurant wait-time fee, the pay would not cover the cost of petrol it takes to cover the distance. For a round trip of 6 km, the distance pay was Rs 23, rain surge Rs 15 and restaurant wait time Rs 18.

Additionally, variable incentives are paid, depending on fluctuating targets. They can be based on the number of orders done (in a particular time frame), amount earned and (customers’) order price. These targets are often difficult for drivers to achieve.

New joiners, says Kiran Anand, receive incentives based on earning targets, without the surge pay, and their low base pay makes it doubly hard for them to reach it.

Another complaint across the board is the expansion of their ‘zones,’, or the areas they operate in. “Before the lockdown, we would get orders from within 10 km. But now our distances go up to 14-16 km,” says Raza, a Zomato delivery partner for three years with a base pay of Rs 30. For every kilometer after the initial three, Zomato pays Rs 6.5, and Swiggy Rs 6. And even though orders can reach the driver anywhere in their zone, the frequency of orders is not equal everywhere. The ride back till receiving the next order is at the driver’s expense.

The Swiggy Smiles program, a loyalty program, was also stopped. It rewarded delivery workers and their families with an assortment of shopping vouchers, movie tickets, loan and scholarship assistance, on-call doctors, etc.

In return, a blog post on Swiggy highlights Swiggy Suraksha, a programme offering healthcare and support for Covid-19 afflictions. It offers paid time off in case of Covid-19 or a death in the family, a 24×7 emergency hotline and physician support. It even offers medical and life insurance, at Rs 1.5 lakh and Rs 5 lakh respectively.

Distorted wages and working conditions

For most delivery apps, incentives, pay and order frequency are not uniform across drivers of a company, even in a single city. Senior partners typically receive a higher base pay, having joined when the base pay was higher and due to an incremental increase. Drivers that regularly hit targets, deliver ‘lightning fast’ and log longer hours have more orders coming their way. Customer ratings can also drastically affect a drivers’ standing.

“In Zomato, drivers are divided into tiers: Blue, Bronze, Silver and Diamond,” says Kiran. The bottommost level, Blue, receives the fewest orders and no insurance. The frequency of orders rises with the levels. To raise a level, a driver has to over perform. Getting to the Diamond tier requires no denials or cancellations, a near complete on-time delivery and a five star rating.

A single delay or order cancellation (from the drivers’ side) costs the driver Rs 40 and could attract a penalty. Even denying an order has a negative impact. Asking many questions off customer service and logging in infrequently can lead to an ID being blocked. Justified reasons, like bike trouble, are usually not taken into account, say the delivery workers we spoke to.

The discrepancy in pay and nature of gig jobs weaken efforts to unite all workers and unionize. The companies can respond to strikes by terminating their IDs. The Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers (IFAT), which is the umbrella Union for app-based transport workers in India, learnt about such a strike in Navi Mumbai last month.

The strike ended with the workers writing apology letters to Zomato to have their IDs restarted.

[Note: Some names have been changed upon request to protect their identities.]