Until about four months back, if one were to walk through the small by-lanes of the Savda Ghevra resettlement colony in North-west Delhi, it was common to find women sitting at their doorsteps alone or in groups, assembling toys from sacks of colourful plastic pieces. Others would be deftly cutting out sandal straps from long rubber sheets and bunching them up in sets of a dozen pairs each, while again others would be doing intricate bead work in a manner that seemed almost effortless.

With the onset of COVID-19 and subsequent lockdown measures announced to curb spread, they can no longer be seen.

The type of work described above is home-based work, a kind of informal employment that engages a large section of women in many urban poor settlements of Delhi.

Home-based workers undertake paid work from within the confines of their own homes or premises. While some of them are self-employed, buy their own raw materials and sell the finished goods to local customers, others are subcontracted by larger firms in domestic and global supply chains.

Home-based workers in Delhi are engaged in a range of trades, from manufacturing to packaging, repair and food-processing. They can be seen doing highly-skilled hand embroidery and embellishment work for large global fashion brands, finishing up products manufactured in small factories, or packaging different kinds of products for sale. They receive this work through middlemen or subcontractors and are mostly paid at piece-rates.

Even though home-based workers work for long hours and contribute significantly to both their households and to their employer’s value chains, they are hardly ever acknowledged. Their work is undervalued as ‘time-pass’ activity and these workers do not get any of the protections or benefits that a worker is entitled to.

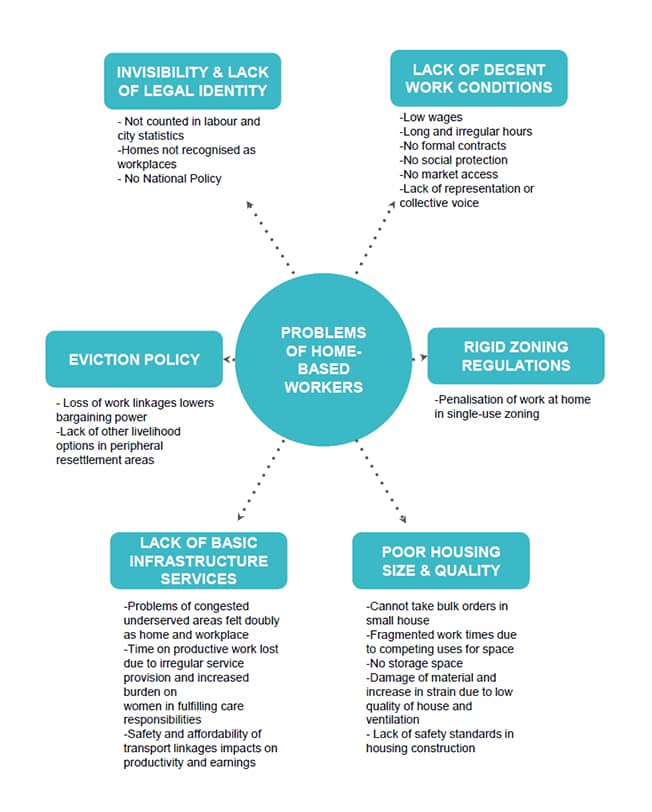

The following chart maps some of the key issues faced by these home-based workers:

When work dried up

In the past few months, many of these challenges have been exacerbated. There is virtually no work coming into the colony. Many of the factories in the city, from where contractors used to source work, are shut and the middlemen themselves are out of work.

Many women workers have unsold inventory and have not been paid for previous orders. Those who are self-employed are also without income, as they cannot meet with customers or go to the markets to procure raw materials. Today, even as the city is slowly opening up, it is still unclear if or when orders for home-based workers will revive.

The loss of income is causing severe hardship. Many of these workers have been unable to meet even their basic needs for food or milk. While a small number found an alternative way to earn money — making masks, for example — or have another breadwinner in the house, others are in extreme distress. All or most of their savings have been used up and many workers have had to either sell their assets or borrow from moneylenders at high interest rates.

The risks of contracting COVID-19 are still very high, which prevents workers from going out and looking for work.

Most home-based workers are women who face additional demands on their time for household chores, cooking and child care during the pandemic. And since schools and child care centres are closed, that work is without respite.

What they need

The need to increase the visibility and recognition of home-based work is a longstanding demand and is even more urgent now:

- In the short term, targeted support for recovery of livelihood is a must. Many home-based workers are adept at tailoring work and governments need to engage them to manufacture masks and other essential protective equipment for which demand is now high, so that their skills can help others while enabling women workers to earn much-needed income for their struggling families.

- Organizations of home-based workers are also demanding that brands extend a one-time Supply-chain Relief Contribution (SRC) to all workers in their supply chains, during the COVID-19 crisis.

- In the longer term, home-based workers should be brought under the Minimum Wages Schedule and receive extended social security and other worker benefits. All actors along the supply chain, from brands and firms right down to the contractor who finally employs home-based workers, have to be made accountable to ensure decent working conditions as well as occupational safety and health.

In this moment of blurred boundaries between home and work in the face of a worldwide public health crisis, let us remember and stand by those workers who have always been working from within their own homes as an unrecognized but integral part of our economic system.

This post was published on WIEGO’s Delhi Dairy and has been republished with permission (with minimal edits). Read the original post here.