School seems a memory of the remote past. The play dates have stopped too. Add to it a general sense of foreboding, constant restrictions and in some cases, illness and death witnessed in very close circles. Children, both my own and among friends and family I’ve spoken to, are terrified with what’s going on. They’re also lost and confused.

First, they’re afraid of catching the virus themselves. My 8-year old keeps smelling things all day to ensure he hasn’t lost his sense of smell. If he feels hot (it’s summer), he asks us to take his temperature. If his legs are sore from running, he asks if it’s a COVID symptom.

In our zeal to get the children to observe COVID-appropriate behaviour, (“Mask up! Don’t play with your friends! Wash your hands!), we may have overused fear as a weapon. Children (and frankly, many adults) cannot assess probabilities well. The worst case becomes the default.

Children are also anxious about losing their parents. A close friend’s six-year old daughter cries every time he steps out of the house to as much as take a walk. She’s convinced that “There’s COVID outside”. My children asked me how kids who have no parents live.

Outside of fear, the uncertainty in both their daily lives and their medium-term future is creating stress for children. One day you can play with friends, another day you can’t. One day your teacher says, “See you in school next year,” another day you’re in lockdown. One day the exams are on, another day they’re not. My nephew said, “I would rather catch COVID than have to prepare for these exams again.”

Read more: How to keep your children safe in the times of COVID-19

Our children are experiencing emotions they have never felt in their short lives, and they don’t always know how to deal with them. From a parent’s perspective, here are some things that are working for us, and some that aren’t, in helping them work through these emotions. This is not advice and I’m only sharing my experience.

Figuring out what works

Our first reaction was to try and shield the kids from talk of the virus. We cut their media exposure altogether, stopped talking about it in front of the children and spoke in hushed tones when we heard of someone getting it. The strategy backfired completely.

Children don’t react to what you say; they react to how you feel. And we obviously can’t stop feeling anxious ourselves. If anything, by depriving them of knowledge of what’s happening, we were only making it easier for them to imagine the worst.

Read more: When the screen is your child’s classroom and playground

Providing general reassurance also did not work for us at all. Our instinct as parents was to hold them close and tell them everything was fine and we wouldn’t let anything happen to them. Unfortunately, children recognise an empty gesture when they see one.

Asking them to stop displaying anxious behaviour is also quite futile. If a child is smelling things obsessively, forcing him to stop it won’t remove the underlying anxiety. In fact, for us the opposite worked: by normalising that behaviour, we allowed him to reassure himself.

A knowledge-based approach seems to be working slightly better for us. I have shown my son statistics on how unlikely children are to get severe symptoms. I told him about a friend’s kid who got COVID and recovered within days.We showed him ongoing trials of the vaccine in kids. We are also cheating a little by using the placebo effect to reduce their anxiety. I showed them research on how lack of stress, sunlight, exercise and vitamin intake is correlated with a stronger immune response. Now they obsessively cycle around the neighborhood in the sun.

For older kids, putting their worries in perspective seems to work. My close friend was able to counsel his 10th-grader that exams and results mean nothing as long as they’re all safe and together. My wife (a middle-school teacher) has used the same approach with her students.

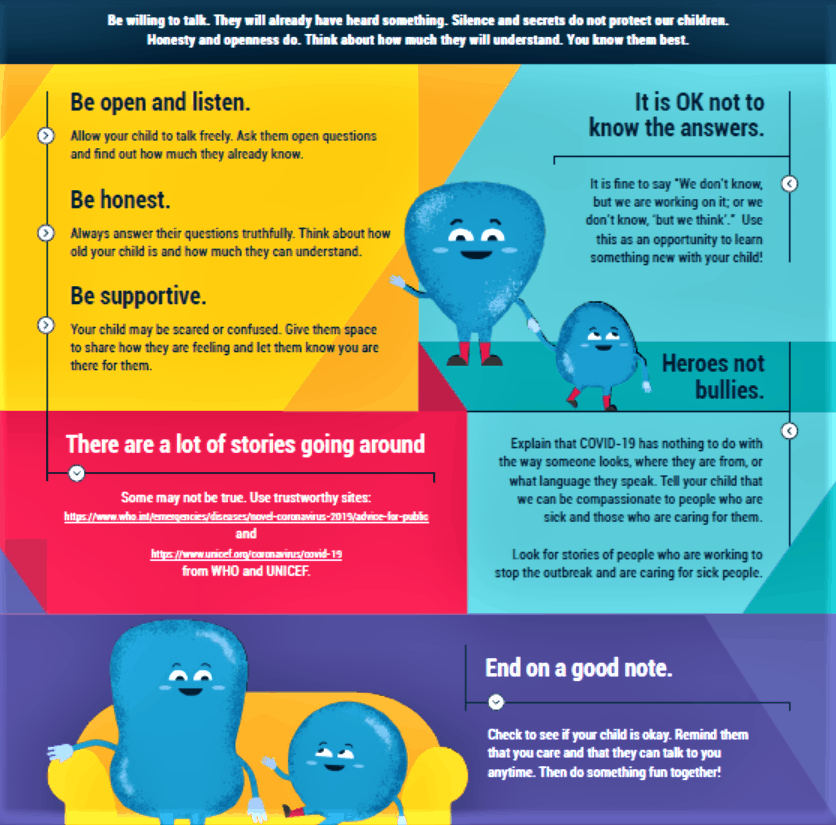

As I shared my concerns above on a social media channel, I came to know that UNICEF too has come up with a set of tips and guidelines to help parents talk to their children about the coronavirus disease and the circumstances that it has created. A lot of it resonates with what we have experienced as parents.The main pillar of the strategy they suggest is again, communication: having an open, supportive and honest discussion with children can help them understand, cope and even make a positive contribution for others.

The important thing is to know that our children are facing unprecedented levels of anxiety and stress, and we need to be alert to the symptoms.We may not always be able to help them, but taking them seriously and offering empathy can be a good first step.

UNICEF’s 8 tips to help comfort and protect your children

- Ask open questions and listen

- Be honest: explain the truth in a child-friendly way

- Show them how to protect themselves and their friends

- Offer reassurance

- Check if they are experiencing or spreading stigma

- Look for the helpers

- Take care of yourself

- Close conversations with care

For more detailed explanation, visit this page.