Narrow, crumbling roads, buildings on either side, cars and pedestrians navigating the maze. I glance at the navigation app on my phone. Less than 100 metres now. But it’s still nowhere in sight. Asking people doesn’t help. And then, seemingly out of nowhere, a sharp turn. The GPS says I’ve arrived: I’m inside the congested urban village of Panchsheel Vihar, in front of Ramditti J R Narang Deepalaya Learning Centre.

The Narang Trust formed by the family-owned Narang Steel, has donated the use of their building to Deepalaya—an NGO—rent-free, for close to forty years. It is within this building that The Community Library Project was born.

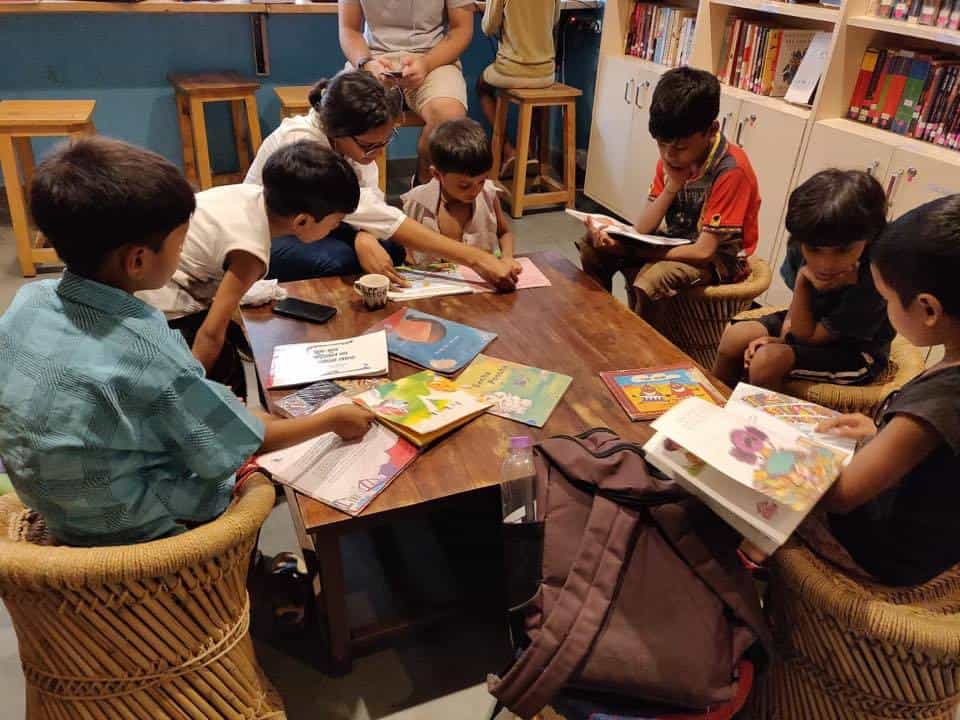

Colourful hand-drawn notes peep out of the large glass windows. A banner across the entrance reads ‘Library’s Got Talent’. Inside, children hop from one room to another. Some with books, a few with cloth dusters. A few others are sitting by the staircase and chatting.

Monica, who oversees the circulation desk at the library, takes me on a tour and tells me how the library is run—by a few staff members of Deepalaya, and several dozen volunteers and students. She proudly shows the roll of honour on the boards in each room—long lists of readers, with stars indicating how many books each member has read. The library is closed on Thursdays for maintenance, she says. But it is open on all other days of the week and on Sundays students line up even before the doors open, eager to return and issue new books.

Set up by Mridula Koshy, Michael Creighton and a dozen more volunteers in January 2015, the library goes beyond providing books and spaces for reading. Living up to its name, the library actively involves the community in running the project, and in organising workshops and events.

A majority of the work is undertaken by the Student Council—a dozen children, hand picked and trained to serve as council members.

Priya Sharma, one of the council members, has just entered the 10th standard, and has been coming to the library for the past three years. Her cousin used to be a council member, and encouraged her to join. She tells me that her school books were boring—it was the storybooks in the library that increased her interest in reading. Reading a few pages from a book before bedtime, is now a normal part of her life. She visits the library everyday immediately after school, through the year.

“As a council member, we do everything that is needed to be done, cataloguing books, running the circulation desk, conducting events… Although Ma’am has told us that we need to give only four hours in a week, all of us give more, some give eight, some twelve. During vacations we’re here the whole day!” she adds enthusiastically. “Every Sunday we conduct assemblies. During the assembly we inform our members about what is going to happen over the coming week.”

When I ask her about the activities, she tells me about the talent show they recently organised, and the forthcoming drama workshop that they are preparing for. “We’ve done three drama workshops. We’re now writing our new drama. The Aagaaz Theatre Trust in Khirki will be coming later this month to guide us.”

Priya introduces me to Sumit Parewa. Like Priya, Sumit came to know about TCLP through someone he knew. Initially, he was only interested in reading. But soon began volunteering. He went on to become a council member, and having worked for six months, was offered a staff position. He now works with the project’s second library in Gurugram.

Sumit tells me he has learnt a lot at the library. Growing a little philosophical, he says, “You know, how you begin to recognise and know yourself—you are progressing, but you don’t even know it is happening. That’s what happened with me. Six, seven months into my involvement here, my mother suddenly said to me, ‘You’ve changed!’ And she said it in a nice way! You don’t know it is happening, but you realise it when you look back after six-seven months. It’s an interesting experience being a council member.”

Membership in the library is free. And there are no monetary penalties for damaged or lost books. Instead, members must help out with maintenance. This explains the dusters I saw earlier in children’s hands. Children are dusting books, ensuring they are kept in their proper place, fixing damaged books, reviewing the catalogue… there’s always work at the library.

“We’ve put a value on books and it’s not money,” says Mridula Koshy, as we settle in for a chat in a relatively quiet room. Below are some excerpts from our conversation.

*****

The beginning

“I’ve been reading to kids in one form or another for most of the last ten years. Deepalaya ran a school in this building and we’d created a school library. I was coming once a week and reading to children. When the school shut down, we asked Deepalaya if we could turn it into a community library, in other words, if we could invite anyone who wants to come in the door. Not just an enrolled student or a tuition parent—anybody from age four to adults.

And they said yes. I think they are just super far-sighted people. It’s difficult to find partners who are willing to do this—people are fearful of opening the door so wide that anyone can come for free.

In the beginning we had forty members, then eighty, then six hundred… The first year growth almost took our breath away. Every month there would be a hundred new kids pouring in.

On the importance of an open admission policy

I think if you look generationally at our members, they’ve been excluded from reading, not just now. Most of our members—99.9 percent—come from within walking distance. At this moment in time, Delhi doesn’t provide more than three dozen public libraries, and they are kilometres apart from each other. Plus the librarian is forbidding, the atmosphere is forbidding, the books are kept locked up and you have to have a letter attesting to who you are. All that stuff stops people.

There is a built-in sense, that this system is burdened and that it can’t meet everyone’s needs. So, it has to unfairly, arbitrarily exclude people. If the government only chooses to build three dozen public libraries in Delhi, and there’s more than 21 million people (sic) in the National Capital Region, then they intend for either 500 thousand people to fit into each library, which they can’t—some of the libraries are only a little bigger than the one I’m running—or they clearly mean for people not to use it. They did not design a public library system for the public. They designed the public library system for people that they will let in. So then they have to come up with some arbitrary things to keep people out. ‘Oh, you don’t have a letter. Oh, you can’t understand the form, you’re out!’

I think our members, our young adults are the easiest to exclude because they come from the least enfranchised population.

The idea that all are welcome, the library is free and open to all is reflected in everything—from the architects who came and opened up the windows, to our open admission policy. Even a child can gain admission without any proof of identification or any security deposit or any letter attesting to the moral strength of their character. Anyone can walk in and say, ‘I want to join,’ and we will do everything we can to give them that. We know it’s best for a child if a parent is involved so we have been pushing hard, especially recently, to get the parent in the space. We go to a person’s house just so we can meet them where they’re comfortable.

Our retention rate is somewhere around 50%, I have very little to compare it with. I feel that it is a good number. We’ve signed up about nineteen hundred children and just about nine hundred and fifty are using the library. What I mean by that is, we look at our circulation programme where books are going out and books are coming back and we’ll look at the last three months and we’ll see nine hundred and fifty have used the library. And consistently it’s about the same. It used to be eight hundred, or 850, and that was half of the total then.

On silence and conversations within a library

We don’t have the luxury of coming to a conclusion about what a library should be. What a library should be, is a question we’re answering all the time. A library should be one in which small children can also take admission. And if their parents do not come, they should still be able to take admission.

Should a library be a silent place? Yes, ideally. But we’re not working with ideal situations!

We have a lot of workshops and programs here. We had a visit from Clowns Without Borders—they were very loud! When the clowns came, they rolled out of their car in the market and they did a parade. They were like pied pipers and yes, there was a stream of children following behind them. We had a hundred kids in here. And I was like, ‘Sorry, no more coming in, it’s a safety issue!’ So then the clowns came in and performed for the hundred children. It was really good.

We constantly have performances, activities that kids engage in, poets who come and read, writing workshops—we’ve had some of the best writers come here. Urvashi Butalia came here twice. Once to talk about the Partition and another time to introduce us to Baby Haldar’s memoir. Both times we had a lot of adults and teenagers here.

We talked about Jyoti, about the rape of that young woman, and about who’s equal. That was a very powerful moment in the library because someone said ‘Yeh kya hai? Barabari kya hai, mard aur aurat ke beech mein?’ (What is this? What is equality between a man and a woman?) She asked, is a middle class woman the equal of a working class man? Is a working class man equal of a working class woman? Is a working class woman the equal of a middle class woman? What is this equality we’re talking about?

She was talking about intersectionality, without using that word. And everyone was left shaking their heads and pondering. The word balatkar (rape) was being used all around the room. And kids were learning that they can use these words and talk about these things. We’ve had lots of gender discussions. The book club is discussing the book Talking of Muskaan, which is a powerful story about a teenage girl.

We invited Breakthrough India, and this year Youth Parliament is coming to work with teenagers on issues to do with self development and self understanding. These are things that we learned as we went.

On sustainability and the larger objective

“Sustainability—depends on how you define it. I think people think sustainability is about how much money can you get the Gates foundation to give you. We’re not thinking about it in those terms. We’re grateful to the Narang Trust, Deepalaya and Agrasar in Gurgaon for giving us access to free spaces. But our model of citizens building small libraries is not what we want in the end in the city. We want a public library system. Of course, we want small bands of citizens to continue to be involved in libraries even after we get to the place where there is a public library system that’s viable, functional and serving all, and not just the current 35 branches.

A public library system has to be publicly funded. When the Aam Aadmi Party puts out an election manifesto which says we will create so many hundred reading rooms where people can come and study, we are disappointed. Our library is a challenge to the idea that libraries and books should be limited to studying. We’re helping people understand what a library is.

A library is a place where people who don’t know how to read, who have not read generationally, can come in. A library is a place where the work of the library can be taken on by the people and thereby the cost of the library can be reduced, which is a huge factor in sustainability.

We’re interested in demonstrating not only what a library is, we’re also interested in demonstrating that reading is thinking, which is something that is absent from Indian curriculum. We do believe that schools have to have school libraries, that classrooms have to have classroom libraries, that children should have access to libraries in their neighbourhood so that they can read in the evening and they can read on the weekends, but additionally, that their mothers can read, their mothers can walk in and borrow a book for the baby brother at home. There’s a multiplying effect that we’re missing from reading in India. Reading has been confined to its most basic and most people have been excluded from a more complex understanding of reading.

Our kids are thinking all the time about the society they are part of and the kind of society they want to make. They also do a lot of thinking around storytelling. They are very used to having stories told to them. With our read alouds, most of them are immediately offering us alternative endings. ‘Ma’am idhar khatam ho gaya? Mujhe nahi lagta idhar khatam ho gaya. Mujhe lagta hai wo baad mein kuch aur karegi’ (Ma’am, it has ended here? I don’t think it ends here. I think she will go on and do something else) So, that’s a thinker. That’s a thinker who knows how to think with narrative.

We also sometimes take a book that we’ve read together and turn it into an arts and crafts project. There’s lots of different ways they are looking at that book after having read it. So pretty much everything we do is about promoting thinking. I am more interested in seeing a kind of sustainability that involves getting tens of thousands of people engaged.

I’m arguing for increased participation in decision making for which we need to develop critical thinking—books are a powerful tool for doing that. And we’re very successful in demonstrating that here.

In our library, for very little money, about a thousand kids are reading, about 500 books go out the door every week and come back, and similarly in Gurgaon. Our library is low cost, replicable and sustainable.

I am not counting on being alone in convincing Delhi. I am counting on the thousands of children who will go through our programme in the next ten years to convince Delhi. Another way of looking at sustainability is how many people can you engage in a movement for change—not how many technocrats, how many government advisors or bureaucrats or special committees to look at curriculum. Maybe we’ll influence those people too. But I know for a fact, because we’re a ground movement, we’re influencing thousands of ordinary people.

*****

Our conversation ends with Mridula being whisked away by the students for their scheduled meeting—a debrief on their recently held talent show. I continue the conversation with Michael, who helped set up the library, and who creates curriculum for the library, is at the library every Sunday for read alouds in English. “There’s more than a thousand kids in this neighbourhood, who have come and taken at least ten books, close to a hundred have gone on to read a hundred books or more, which is amazing—especially because, for the first couple of years the program here only opened once a week. And it’s all in this one little area. That’s the funny thing. I walk in the neighbourhood, there’s about a five hundred, six hundred metre radius around the library where I will regularly get ‘Sir! Sir! Sir!’ And then I leave that space and I know—that’s our range!”

Echoing Mridula’s opinion on the importance of the library system being publicly funded, Michael says, “If you step back, libraries are very efficient and inexpensive, especially if you can pool resources in the community. Most of the work here is done by the community members. These young adults here are running the show. They run the circulation desk every day.”

“They (government) have libraries in schools already. They can expand those—it will be a marginal cost to expand the collection to get reading material for adults. It’ll cost money, but it won’t cost as much as a lot of things governments do. Look at the Delhi metro. The cost of one metro station could build thousands of libraries. If the government says we’ll give you space, we’ll give you staff, and you help with volunteers, open the community—everyone has to come together for this to work. It wouldn’t work if the government did it the bureaucratic way, saying ‘show me your Aadhaar card’. They have to open the doors and say it’s free. And realise that you’re going to lose some books. And you can replace those.”

“If you have a thousand books and you lock them up, they’ll stay safe for a hundred years, but nobody will read them. Eventually you will replace them because the worms will get to them. We’d rather have a thousand books and lose five percent of that, wear them out and eventually buy new ones. The book is read thirty, forty times. That’s good value.”

On efforts to involve adults in the project, Michael says the numbers are on the lower side, but feels hopeful. “Ideally in the long run, we create a whole new generation of readers—these young adults, they’re in tenth and eleventh, ideally they’ll keep coming back to the library when they’re grown ups and then they become our adult membership.”

As we wrap up our conversation, the assembly space begins filling up. A group of children are practicing full-throated musical notes under the guidance of a volunteer. Mridula later informs me that this is an exercise to help the students gain confidence—so that the next talent show they organise, they’ll perform better.

I join a group of students at the staircase and observe what is going on. Next to me is little Meenakshi. She tells me it’s her birthday. Mridula had already mentioned that to me earlier in the day. “She’s turning four years old, and will be enrolling as a member this week. She has been coming here for our read alouds for some time, and is very excited to be a part of the library.”

After Mridula finishes her meeting with the students, I ask her if I can take pictures. She is reluctant, but eventually agrees to using some pictures from their social media feed. “There are two considerations, one is do we have permission, and it’s true that we don’t always; and the other is how are we representing them? A lot of organisations are hell bent on saying, ‘give us money because our kids are so poor.’ That’s not how we want to represent them. This is a group of powerful thinkers and we can all feel like we’re moving in a good direction as a society because these kids are building something.”

As we talk, one young member nudges Mridula and asks “Only those who have read more than 80 books can go to the museum? If it’s less than 80 we can’t go?” Mridula confirms, and gently encourages her, “You’ll also one day have more than 80, no?”

“Yes, it will be soon.”

“We’ll have another trip. We always take the top readers, no? You’ll also reach there. How many have you got so far?”

“Seventy,” she replies.

“Seventy! It is so close. Next time.”

Turning to me, Mridula continues, “We are going to National Museum to see the show “India and the World”. We are taking 36 kids on a bus. We can’t manage beyond that. It’s… not safe.”

I thank Mridula for letting me hang around. “You must come again and see the books we have.” I tell her I will definitely be back.

As I proceed to head out, Meenakshi comes behind me, her hands clasped behind her, looking up at me with wide eyes. She blinks a couple of times and then extends her small arm in a tight fist. I extend my hand. She swiftly leaves a candy in my palm and runs inside.