| Between March 20th and 31st, the first week of the lockdown, around 3.07 lakh calls were received by the child helpline 1098, out of which 30% or 92,105 calls sought protection against abuse and violence on children. This impelled the Deputy Director of Childline India to suggest that the helpline be declared as an essential service during the coronavirus lockdown. Unfortunately, the lockdown has turned into inescapable prisons for children who were trapped with their abusers at home. The closure of schools as well as online classes also create scope for greater exposure of children to online child sexual abuse. Another recent outrageous incident — involving the ‘Bois Locker Room’ Instagram group of 21 boys between classes X and XII from prominent South Delhi schools — also brings to the fore the imperative need to address gender issues through a combination of steps taken by various stakeholders, including counsellors and NGOs involved in tackling Child Sexual Abuse (CSA). April was Child Abuse Prevention month and it brought to light some key efforts that are being made to ensure the safety of our children. In a three-part series on Child Safety and Protection starting today, we look at triggering a continuing conversation on this extremely important issue and explore effective solutions to it. |

In India, as many as 109 children were sexually abused every day in 2018 according to the data released by National Crime Record Bureau. 32,608 cases were reported in 2017 while 39,827 cases were reported in 2018 under the Protection of Child against Sexual Offences Act (POCSO). As many as 21,605 child rapes were recorded in 2018 which included 21,401 rapes of girls and 204 of boys. With such alarming figures, the country is just staring at a future with thousands of mal-adjusted citizens.

All children are vulnerable by virtue of their innocence and the ability to trust others easily. Their gullibility lends them open to harm, injury, violence and abuse. Despite the fact that we have an exclusive ministry for women and child welfare and organizations like Indian Council for Child Welfare, we have not been able to curb the increasing incidences of violence against our children.

“This is a huge problem,” says Girija Kumarbabu, formerly Hon. General Secretary of the Indian Council for Child Welfare, Tamil Nadu, who has over 35 years’ experience in the social service sector, “If we can make strong, concerted efforts – comparable to the recent imposition of Sec 144 of the IPC during the lockdown – it may probably work.”

According to Girija, there are many variations of child abuse and it is difficult to get to know what happens within the four walls of a house. The greatest challenge seems to lie in changing people’s perspectives of their own sexuality and gender bias. “We still look at women as pleasurable objects, the reason why a girl child, a young woman or even an old woman is not spared from sex crimes,” she points out.

Not just physical abuse but cybercrimes against children are also on the rise. Girija says that with more children accessing the net, keeping them safe from cyber-predators has become one of the biggest challenges in recent times.

So what is the way out?

“We need to build programmes extensively that project women as equally worthy of respect as men. The change should start very early, right from school. All folklore where women are projected as objects of pleasure must be removed,” says Girija, “The laws are stringent and have strong sections where those who perpetrate abuse against children can be incarcerated. Mahila courts are designated as special courts to handle POCSO cases. One major issue is the lack of evidence. Evidence collected by the police is often not enough to enable a judge to mete out rigorous punishments.”

The difficulty of getting actionable evidence

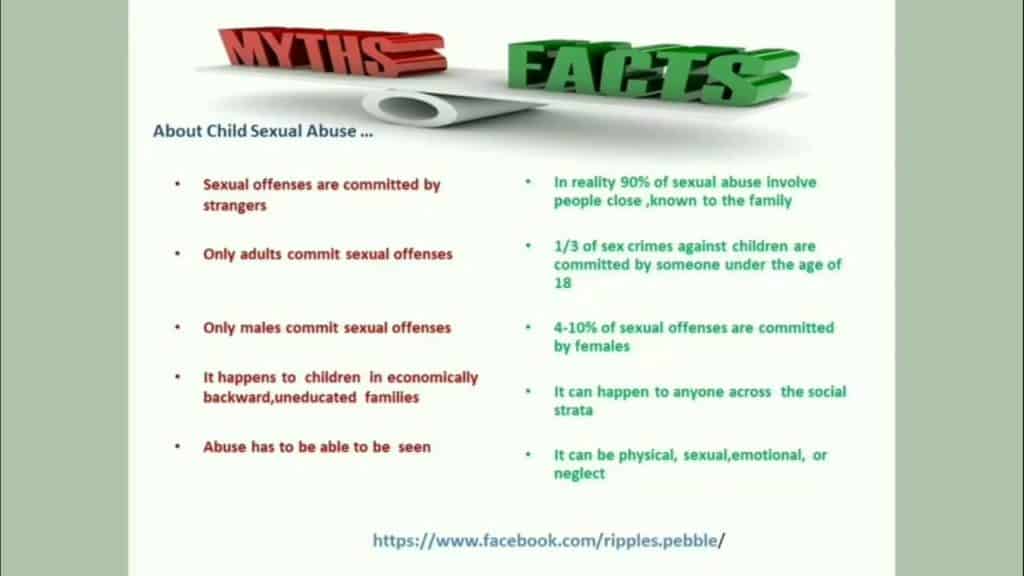

Minors in general, and especially those below 12, do not have the independence to complain against abusers in the family, like their father or brother. Given that in many cases, the perpetrator is someone known to the sufferer, completing the due judicial process and getting the abuser convicted is difficult. Often, just before the final judgement, the child goes back on her statement and then the entire case falls flat.

Girija cites a case where a girl child was trafficked and kept locked up by a person known to her, who also brought two other persons to abuse her. She was later rescued by the ICCW. During the inquiry, however, the girl incriminated only one person and the other two went scot-free.

In another instance, a woman brought her two children to the ICCW who were being abused by their father. She was not willing to report her husband, but wanted some help for her children. “The ICCW cannot report against the mother’s will. The mother will play on the children’s minds saying that the father will be punished and go to jail and coerce them into saying that the father did not do anything,” says the former general secretary.

One major issue is the lack of evidence. Evidence collected by the police is often not enough to enable a judge to mete out rigorous punishments.

Girija Kumarbabu, Former General Secretary

Indian Council for Child Welfare, Tamil Nadu

Even medical examination of abused children does not yield strong-enough evidence as government doctors rarely give certificates that state categorically that the child has been abused. It has been observed that in most cases, the doctors take a safe route, mentioning that injuries could have happened due to other reasons also, which negates the whole exercise of building up strong evidence against the accused.

This happens more often than not due to the prevailing patriarchal mindset and other considerations such as the family’s honour, the girl being victimised or even if the abuser is considered powerful or sheer apathy on the part of the government doctors.

Laws, implementation and implications

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act in India is a powerful act which expounds strict punishment without parole in cases of crimes against children. Such provisions of the Act as well as judgements where the convicts are given rigorous punishment must be highlighted by media to create awareness and sensitization.

Usually when the father or an earning member of the family is the abuser, women do not come forward to complain even if their children are abused, due to financial reasons. The Juvenile Justice Act provides for non-institutional services for children who can live with their family, even if the only earning member who happens to be the abuser is sent to jail and the state provides monetary support to the family. The child can also be placed for adoption or foster care. The state has to award sponsorship for the child for a period of 5 to 8 years or even 10 years if the child is very young.

However, in most cases, that is not enough. For example, sponsorships from the government in Tamil Nadu are restricted to just 30 and the budgetary allocation by the State for child protection in general is minimal.

Girija strongly feels that the compensation as well as the sponsorship amounts must be sufficient enough to encourage more and more women to come forward and complain, without worrying about their financial security.

To encourage reporting of crimes against children, the JJ Act has also introduced important changes. According to the Act, now the child need not be produced before the law and order authorities, or the court, as was mandated earlier and which could instil fear in the child as well as the mother, deterring them from seeking help. It is enough if the child is produced before a child welfare committee, but even that is not always done.

The POCSO Act lays down that a support person should be appointed for every child. That has also not been followed in many cases. Many provisions of legislations for child protection are not being acted upon on the ground, which is why NGOs and CHILDLINE 1098 become critical to ensuring that children get justice and are protected.

| CHILDLINE India Foundation Ministry of Women and Child Development established CHILDLINE India Foundation in 1999 to set up, manage and monitor CHILDLINE 1098 service all over the country. CHILDLINE 1098 is a helpline (phone number) available 24-hours a day, 365 days a year and is a free, emergency phone service for children in need of aid and assistance. They not only respond to the emergency needs of children but also link them to relevant services for their long-term care and rehabilitation. Till date they have connected three million children across the nation, offering them care and protection. Who can dial 1098? A child – Any child can dial 1098 to get in touch with the CHILDLINE India Foundation team, who will reach out to the child to help, keeping the name and identity of the child confidential. A concerned adult – Any adult who is concerned about a child can dial 1098 to help the child. Family/relatives – Any family member who is concerned about a child in their immediate or extended family can dial 1098 to help the child. CHILDLINE Network – If any partner of CHILDLINE India needs assistance they can dial 1098. |

Looking beyond laws

Girija underlines that schools must start educating children right from the primary section on how to look after themselves and suggests a few steps to be taken by them.

Educational institutions often do not want to talk about abuse. The general approach is to assume responsibility for only as long as the child is within the school premises. Schools should not say that a child is not their responsibility once she steps out of the premises. During PTA meetings, they should organise sessions on child protection instead of focusing only on the child’s academic performance.

Every school bus driver must have undergone police verification. Bus drivers too should have sensitization sessions. Schools should have complaint boxes which should be opened by the headmistress and a member of the PTA.

Today even poorer economic sections and rural people can have access to institutional child protection. On paper we have strong and vigilant child protection committees, mechanisms to ensure that people can complain and get justice. Laws are in place. What is required now is interdepartmental coordination and joint efforts by all stakeholders, that will keep our children safe and protected.