In July of 2022, the Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA) introduced the ‘Shoreline Renourishment and Revitalization Project,’ a large-scale version of many beach beautification projects introduced in past.

The overall project will cover just over 50 km of Chennai’s coastline with various sections being developed along various themes. A Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) has been constituted to carry out the project with the body comprising officials from various departments.

Chennai citizens have consistently brought forth concerns surrounding beach beautification projects in past years, mainly as it had to do with fisherfolk and the environment.

Will the planning for the extensive revamp of the city’s beaches take them into account? What changes can be expected once the projects are initiated?

Read more: What to expect from beach beautification plans for Chennai

Displacement of fisherfolk due to shoreline project

The initial proposals of these beach beautification projects include large infrastructure that has the potential to displace fisherfolk. Some of these are ramps for disabled people, cycling walkways, and even new recreational structures like gyms.

“The beach is where fishers keep their boats and their nets.” says Ajit Menon, Professor at Madras Institute of Development Studies “The state often takes land which they feel they have the right to take, so on the coastal side, that is the big issue. If you start talking about beach beautification and industrialization, how do you account for what people consider their prior rights?”

Ajit explains that many fisherfolk have been fishing for many generations from the locations throughout the coastline, and consider the land to be rightfully theirs.

When asked about the potential damage of these, a CMDA official told Citizen Matters that such large concrete structures are not part of the plan unless there is a clearly felt need for it.

“Everything that’s been envisioned will not be entirely concrete-free. Some of the locations will have some concrete structures but there will be erosion-friendly designs,” says the CMDA official.

“Most fisherfolk reside in lands with patta and they will not be affected by displacement. We will not disturb entire settlements for these plans,” says the official. “In places where there is a need to move people, we will analyse what needs to be done. We will have to prove them with an alternative. Neither the government nor the CMDA is looking to entirely displace them from their settlements.”

In the past when fisherfolk have been displaced, the government has worked to provide some alternatives. In the case that these beach beautification projects result in displacement, the CMDA assures that mitigation will take place.

Construction will impact water quality, so what happens to the catch?

On top of the possibility of physical displacement due to new infrastructure and construction, there are concerns that these beachfront plans are very likely to worsen already existing water quality issues.

S Janakarajan, President of the South Asia Consortium for Interdisciplinary Water Resources Studies, (SaciWATERs), is one of the 65 signatories of a petition opposing beach beautification plans owing to concerns about the impact on livelihood and the environment.

Due to increased salinity — a result of polluted waters — fish are dying, and this will only worsen if these projects are taken up. If local water is polluted, fishermen will have lost most of their livelihood, as they will have no reason to fish in these waters if there is no catch, say experts familiar with the ecosystem.

“The coast is now becoming more and more polluted, contaminated, and encroached because of a series of anthropologic activities,” says Janakarajan. “That results in fish catch getting slowed down, several species are disappearing, and most importantly, the fisherfolks’ livelihood is getting increasingly disturbed”

The effects of this phenomenon have already been seen in the Northern part of the coastline, in Ennore particularly, where fishermen are quickly losing their livelihood, and despite protests nothing has been done.

The CMDA official says that the concerns on issues with livelihood will be accounted for and that in places where fisherfolk and women are currently selling fish, they are doing so in an unorganised manner but that the agency is looking into ways to help make the markets available for the sale of fish more organised.

Chennai coast already vulnerable; will shoreline project make it worse?

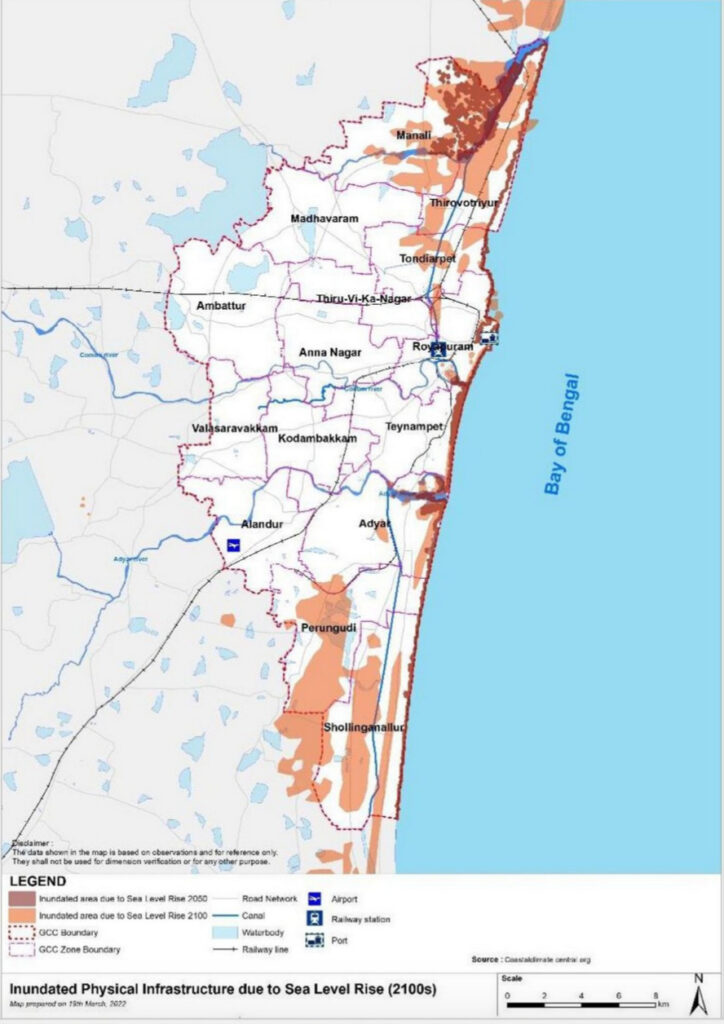

This past June, a study done by the GCC and C40 cities detailed various areas of the Chennai coastline and when they are predicted to be underwater. It was found that by the year 2050, a majority of the current Chennai beaches will be underwater if preventive steps are not taken.

Coastal inundation is a result of various factors, mainly from global temperatures rising, ice caps melting, and therefore sea levels rising. In addition, a side effect of global rising temperatures is increased irregular weather patterns, so things like tropical storms have more potential to erode shorelines.

“The biggest worry now is coastal erosion, particularly in Chennai, it’s very high, and it’s all because of our activities,” says Janakarajan. “This Tamil Nadu Coastline is getting more and more disturbed and that causes a real worry: coastal flooding, shoreline change, seawater intrusion, and all kinds of interventions in the people’s day-to-day activity.”

In the interest of preventing further damage, Coastal Regulation Zones (CRZ) were created in 1991, in hopes of outlining where various recreational activities should and should not be taking place.

Something like these could help keep beach beautification projects in check, but while these regulations are there on paper, historically they are almost never followed, and people are concerned these rules will be neglected again during these projects.

“Every year we are diluting the existing laws of coastal regulation zones,” says Janakarajan.

Saravanan, an expert in advocacy for fishermen right’s and organiser of the Vettiver Collective, explains that since the Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) is still working to create a feasibility report, only after they complete these will they be able to tell whether zone violations are likely to occur during the CMDA project.

A CMDA official told Citizen Matters that the SPV is still in the process of finalising its composition and stated that they would work to prevent any potential violations.

Even with these supposed protections in mind, Saravanan feels these violations are inevitable, especially as it has to do with the idea of connecting all of the beaches on the Chennai shoreline.

Read more: Fishers of Ennore demand their river back

Cosmetic changes exclusionary: Experts

“Beach projects are a very highly profitable industry, particularly for big tourist attraction spots like Chennai. This is only an intervention that will attract tourists. In what way is it going to improve the livelihood of fisher folks?” asks Janakarajan.

“I’m not opposing tourism, my impression is that especially high-end tourism tends to become very exclusive,” says Ajit. “I mean I live right next to the beach, so the idea of beautifying the beach is quite appealing to me, but how do you do that in ways which are inclusive.”

Community members outside of the fisher population are also concerned about the advocacy for those groups that use the coastline for their livelihood.

“Beautify or don’t beautify, I don’t care, but as far as I am concerned this is a cosmetic intervention: superficial,” says Janakarajan. “It doesn’t matter to me at all what matters to me most is the small fishermen: and the vulnerable sections of the populations.”

Fishing populations have already started voicing great concern for this initiative.

“We are concerned with the eco-sensitive areas that fall under the project, such as all of Elliot’s beach,” says Saravanan. “The project will affect the lives of fisherfolk, we are opposed to it for this reason.”

CMDA’s response

The CMDA provides some assurance in response to these concerns, stating that they have heard these concerns and are working to ensure the SPV will include stakeholders and overall a well-rounded group of people, so that these plans are executed fairly, and benefit everyone.

“There will be members drawn from many line departments such as the Fisheries Department, Environment, Forest and Climate Change Department, Revenue Department, Pollution Control Board, and Urban Habitat Development Board along with the civic body, NGOS, subject matter experts and other stakeholders,” says the CMDA official. “The project will be executed in phases, and executed in smaller projects, with the goal of hearing community voices along the way and changing accordingly.’

“We also want to make it clear that the plan that will be evolved will be flexible and moulded according to the needs on the ground,” says the CMDA official. “It is not that the plan will be designed by those in an office without consideration for how the lives and livelihood of fisherfolk can be improved.”

With work already underway in the ECR area for the project, more initiatives will be kickstarted in the coming months.

The CMDA official estimates that the complete transformation according to the plan will take at least five years as we will be working on close to 52 km of the shoreline.

With the proposed projects still in their early stages, only a few community activists have rallied around their concerns. Groups like the Vettiver Collective have kept a close eye on these initiatives in the past. The group has filed petitions that have historically stopped similar projects altogether.

It remains to be seen if the broad assurances by the CMDA on protection to be accorded to the fisherfolk and the promise of ensuring no damage to the coastal environment holds good in the face of sweeping change that awaits Chennai’s shoreline.