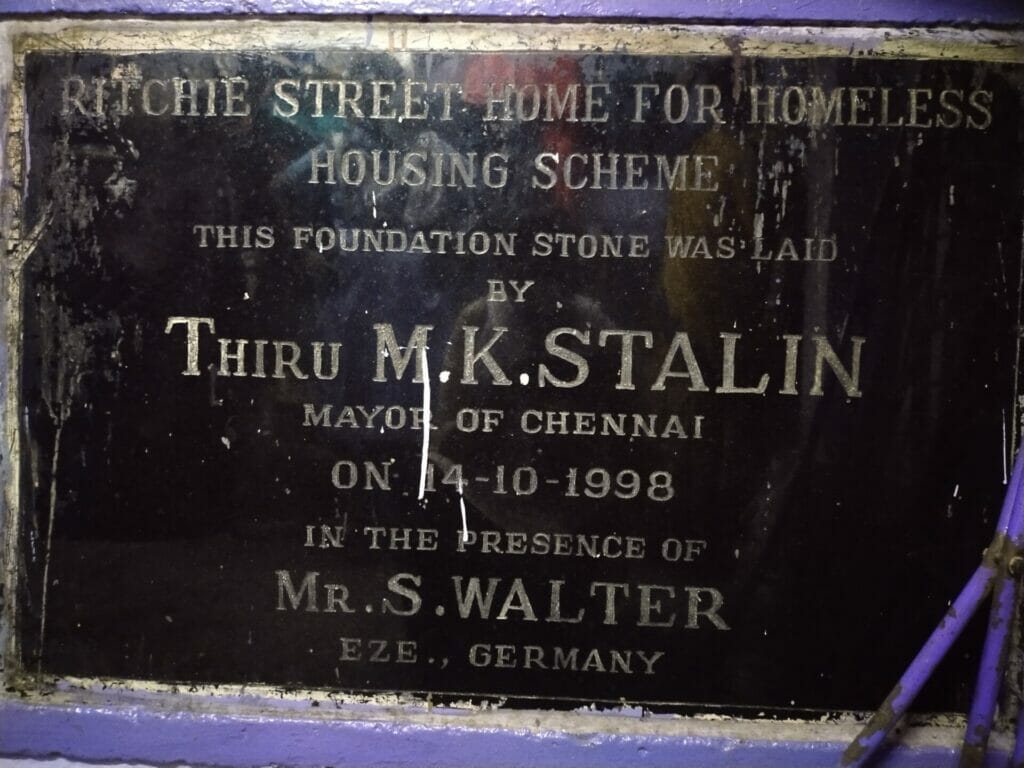

In 2000, as many as 96 families who had been homeless and residing on footpaths in and around Chintadripet were provided with a new lease of life under the Permanent Shelter Scheme of the Housing and Urban Development Corporation (HUDCO). But two decades on, the families residing in the Ritchie Street Home for Homeless Cooperative Housing Society find themselves in varying degrees of debt and uninhabitable living conditions.

What were the promises made to the families on resettlement? Where did the project fail?

Debt owed by families in Ritchie Street housing

The 96 resettled families were provided with one-room flats with kitchen space and shared a bathroom and toilet with one other flat. The homes provided to them were on land provided by the Greater Chennai Corporation on lease.

A complicated arrangement between the state and NGOs was in place to finance the project. According to a report by the Information and Research Centre for the Deprived Urban Communities (IRCDUC), Community Development Information and Action Centre (CODIAC) an NGO, with additional funds from EZE, a German missionary agency, through a Grant cum Loan project from HUDCO, facilitated this project along with Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) and the Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board (TNSCB).

EZE provided a grant for Rs.62.54 lakhs, CODIAC contributed Rs.7 lakhs and the beneficiary’s contribution was Rs.7.08 lakhs, i.e 8000 per beneficiary. HUDCO provided a loan of Rs. 24 lakhs for this initiative.

The loan extended by HUDCO was on the condition that CODIAC will be responsible for the collection of the debt over 55 quarterly instalments between 2000 and 2014

Though the flats were allotted to a head of the household through a lease deed, families can only claim ownership on repayment of a loan amount with interest.

But issues arose with the repayment of the loan amount of Rs 24 lakhs by HUDCO, with families alleging that CODIAC, the NGO in charge of the collection of debt, stopped collecting payments from them as early as 2005. The families claim they could not identify how payments were to be made when the NGO stopped collection.

The matter was escalated to the Debt Recovery Tribunal which ruled in 2015 on repayment by the families and reduced the interest rate for the debt from 13.5% to 6%.

The total amount due from the resettled families was to the tune of Rs 70 lakhs, with each family having a liability of Rs 74,000 per beneficiary as a one-time settlement.

The families have repaid loan amounts to the tune of over Rs 11 lakhs and find themselves unable to repay huge sums given their socio-economic conditions.

They are under a constant threat of eviction due to non-payment of dues.

Read more: Kannappar Thidal: Where residents continue their 20-year wait for a proper home

Nagarani, a 70-year-old resident says, “We were paying the rent for a few years. After my husband passed away, I cannot manage even the house expenses. Now, my son is handling the debt. We have documents of how much we have paid back but we are not owners of these houses as we have not been able to pay the debt.”

Most of the people here are daily wagers. The women work as housing-keeping staff at the nearby housing complexes and other offices.

“When we were allocated the houses, the officials only asked us to pay ‘as much as we can’. We were not given any deadline. They did not say that a fixed amount has to be paid every month. But, after a point, we were unable to pay any amount as we are finding it hard to make ends meet,” says Nagarani.

Lily, a 50-year-old resident of the locality says that initially, the families paid Rs 8,000 before the houses were allocated to them. Later, when the houses were allocated to them, the residents were told they had to pay Rs 25,000 for each housing unit.

This debt amount differs from house to house based on the amount they have repaid so far.

On the other hand, since the senior citizens have moved out of those dwelling units due to space constraints or since most of them have passed away, the responsibility to repay the debt has fallen on the next generation.

“My grandfather started paying the debt. It was followed by my father. Now, I am paying for it. Yet, it does not seem like we can ever get out of this trap. At this point, I even wonder what is the point of paying the debt for a dilapidated building. Even if the government comes forward to reconstruct the building now, I do not think we will get out of this debt trap,” says M Malar, a resident.

The state of housing in the three blocks where the families have been resettled has deteriorated drastically, leaving them questioning whether they should make payments towards a structure that is increasingly dilapidated and uninhabitable.

Poor condition of Ritchie Street tenements

Residents in the three blocks have been disillusioned by the lack of civic amenities and worsening state of living even as their debt piles on.

The buildings have proven to be a safety hazard. A year or so ago, a balcony ceiling collapsed and fell on an old woman. She sustained severe injuries.

Exposed EB wires are also a common sight.

Read more: Photo story: Life in single-room homes in Chennai

The staircases are filled with garbage at every nook and corner and stray cats and dogs can be seen feeding on them.

When the building was built, a cement tank was also built at the terrace and pipelines were connected to the individual houses. Over the years, the pipelines have been broken and the government took no measures to fix them. As a result, all 96 houses now depend on one hand pump. They had to fetch water in plastic pots and carry them for three floors.

The sewage lines too are also damaged and the wastewater from the sewage pipelines remains stagnant in the common areas. Despite being less than 50 metres aware from the CMWSSB office, the residents are forced to attend to such issues all by themselves. As there are many children in the housing unit, it also poses health risks.

Without provision for water in toilets, water has to be pumped and carried in pots to the toilets.

With each house measuring around 10×8 feet, there is not enough space for the residents. Each family consists of at least one senior citizen, husband, wife and two to three children.

“My husband and two sons sleep on the narrow corridors, while I sleep inside the house with my daughter,” says Malar.

On the other hand, as there is no space to accommodate senior citizens in such small rooms as the family keeps growing, the senior citizens have started setting up houses around the building using temporary materials like cardboard and asbestos sheets.

As there was no support from the government for these residents during the pandemic, many children eventually could not pursue online classes and have become dropouts. The children have started taking up odd jobs to support their families.

Many children and youngsters are becoming addicted to drugs and alcohol and dropping out of school at an early stage.

What the residents of Ritchie Street housing society want

“There is no point in repaying a debt for a building that will collapse anytime now. We want the government to conduct proper enumeration. Demolition of the existing building and building alternative housing for us free of cost with sufficient space to accommodate all the family members is necessary. We need a safe space for our children to play. There is enough land here to build houses for us but they remain unused. We do not want houses to be allocated on any outskirts of the city,” says Malar.

While the aim of the project was to remove people from the precarity of homelessness and provide housing, the residents find themselves trapped in a cycle of debt due to poor handling of the financing.

With many residents being daily wagers earning a low income, they find themselves unable to pay the one-time settlement to claim ownership of the homes they have resided in for over two decades.

The Ritchie Street housing project is a lesson on how resettlement if managed poorly, can turn into a daunting situation for the urban poor.