Ever wondered what happens at public consultations for major government projects across Chennai?

“Usually at these hearings, they want to show that they have taken the consent from a wide array of people; from well-off residents to a few fishermen. But when we are given a chance to speak, it is only in terms of ‘yes or no’,” says Velayudam, a fisherman who had attended a public consultation on the construction of stormwater drains in East Coast Road.

Velayudam wanted to speak about how such a project negatively affects the lives of fishing communities living in Sholinganallur. He was of the view that it would destroy the groundwater that all of them depend on for drinking and result in the seawater and rainwater getting mixed up, and could kill the fish and marine life near the shore.

“The drain construction is a matter of life and livelihood (“Ennodiya valvadaram”), and I wanted to highlight that. I wanted to show that we are thinking about this all the time, but all we got to say was a yes or no,” he says.

Public consultations are regulatory tools through which governments consult citizens on public policy issues and development projects. A most recent example is farmers’ participation in public consultations for the second airport in Parandur, near Chennai. Often, many social movements that resist development projects – because they are harmful to people’s livelihoods and ecosystems or due to the threat of eviction – aim to push for public consultations when the projects are announced.

However, despite the promise of a platform for common citizens, public hearings are often contentious spaces. A few examples from Chennai highlight the various ways in which this key exercise has been rendered toothless.

Public consultations are organised as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process, The Social Impact Assessment under the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013, among other laws.

Within the EIA process, the hearings are conducted under the supervision of an Expert Appraisal Committee – from the Ministry of Environment and Forests – and a State Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC) which are to carry out detailed scrutiny of the minutes of the public hearing to decide whether development projects can receive environmental clearance.

Presence of ‘force’ at public consultations in Chennai

The presence of ‘force’ at these meetings prevents many from speaking freely about their concerns. Force can take the form of heavy police presence, the presence of local politicians, control over the mic, etc.

“Often you will see politicians and local MLAs sitting at the dais, moderating these hearings, or party members filling up at least half the hall”, says Nityanand Jayaraman, an activist who has worked with environmental movements over time.

He uses the example of the public consultations in Chennai set up for the Waste to Energy incinerators which were to be built in Perungudi and Kodingiyur in 2017; a project which received considerable opposition from people living near the landfills where these would be set up.

“I remember as soon as I stepped in, I saw a high-level elected representative belonging to the ruling party sitting at the centre of the stage, mic in hand overseeing the whole event.** The front two rows were swamped with ruling party cadres, many of whom refused to share the mic,” says Nityanand.

The chaos that followed was extremely tough to break through and was forceful in its own way. “We had to go and snatch the mic, there was pushing and pulling and all kinds of unpleasant things. This was not a place where someone who is very meek can come and speak”.

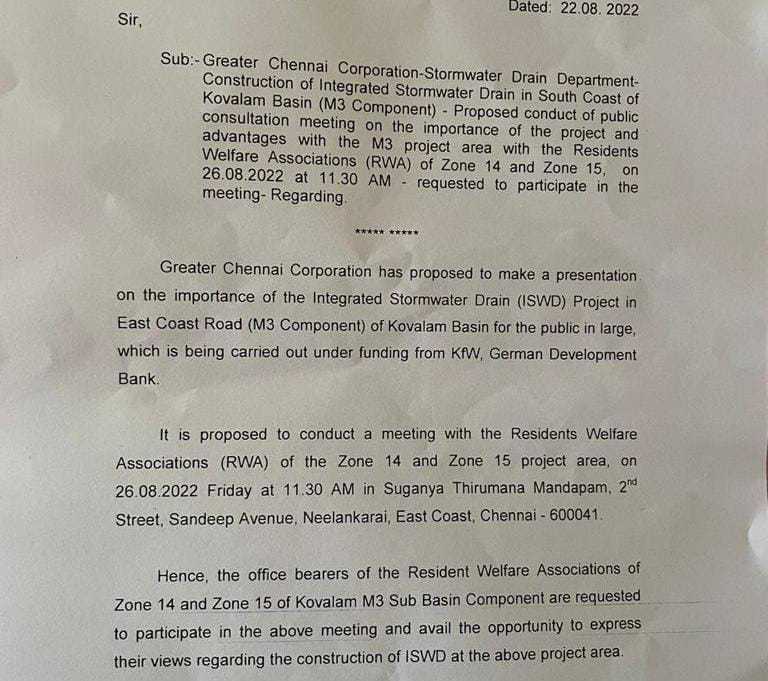

A similar sense of chaos was seen in a recent hearing held at Chinna Neelangarai marriage hall, regarding the construction of the Integrated storm water drain (ISWD) in the South Coast of Kovalam Basin in East Coast Road (ECR), proposed by the Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) with funding from a German bank.

“Eventually, people started to shout over others as they were being interrupted so much and often people opposing the project had the mic snatched away from them. Many of us were also interrupted mid-speech, with the question: “Do you want the drain or not, yes or no?,” says Amarnath, a long-time resident of Neelangarai.

This is the same meeting about which Velayudam expressed his concerns, as stated above.

Read more: ECR residents do not want a storm water drain; here’s why

Cherrypicked demographic in public consultations in Chennai

The ISWD hearing also showed how audiences can be manufactured to project a positive inclination towards a project.

According to residents who attended the meeting, the stormwater drain was to be constructed on the sandy areas in ECR. However, people from the eastern side of the area were invited and made to speak. It is important to note that people from the eastern side had more concrete ground, resulting in their area getting flooded often. However, their areas didn’t come under the project’s scope. They were not only invited, but were the only ones allowed to speak freely without being interrupted.

Another example is the public consultations in Chennai which were held for the Perungudi and Kodungaiyur waste incinerators, where around 100 Amma Canteen workers who did not even reside in the vicinity were invited. According to reports, few of the workers mentioned how they were invited under the pretence of a hygiene meeting. Half the audience then appeared to not know anything about the project, much less the purpose of the meeting itself.

Citizen participation made deliberately complicated

Many of these hearings are not publicised very well and seem to be held in hostile, inconvenient places and at odd times, whereby a majority of those affected by these projects cannot participate or make a representation.

This was evident in the ISWD construction hearing where a few residents part of the Storm Water Drain coalition were only notified a week before the hearing. No kuppam (fishing village) received any official notification, with Velayudam coming to know of the hearing through one of the residents who was a member of the nearby residential welfare association.

As per the laws around the EIA, The Pollution Control Board is to widely publicise a public hearing before it is held. A notice giving the following information has to be published at least 30 days before the date of the Public Hearing:

- Date and time of the public hearing

- Venue of the public hearing

- Places at which the required documents will be available

The notice should be published in one major national daily newspaper and one regional vernacular daily/official state language newspaper. In places where the newspaper does not reach, the competent authority is supposed to publicise the hearing through other means – drum beating, announcing on radio/ television etc.

The public hearing for the Ennore Thermal Power Station (ETPS) is an example of a consultation nearly impossible to attend. The Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Corporation Limited (TANGEDCO), which is the body in charge of the project, tried to bypass the hearing by claiming that the ETPS project had already conducted all of the public consultation requirements in 2008. However, the National Green Tribunal, after protests from local fisherfolk, ruled that a fresh EIA needs to be done considering its older clearance had lapsed, including the mandatory public hearing.

TANGEDCO then decided to hold the meeting during the third wave of the COVID-19 virus in January 2022. As per the rules provided, only 30 people could attend the consultation, completely diminishing the numerical strength of any possible opposition. When many fisherfolk and activist groups asked for the consultations to be cancelled on the grounds of safety during COVID, TANGEDCO stated that it would continue with the hearing. On seeing the massive turnout to the hearing (beyond 50 people), the meeting was ultimately cancelled.

Uninformed consent and lack of information

Another criticism around these meetings is the ways in which the State and the private partners or consultants involved do not put up the Environmental Impact Assessment for the project beforehand. In addition, the information in the EIAs or documents released beforehand is inadequate and often inaccessible.

The hearing for the Coastal Zone Management Plan in 2018, required that adequate information be provided on the land use of coastal commons be included in maps and records. Fisherfolk unions who opposed the hearings at that time stated that the maps used to come to these conclusions were inaccurate. For example, the maps showed roads situated above the Adyar River, and even categorised fishing hamlets located on the east of Besant Nagar as part of the Santhome area. In addition, they did not contain information on land use, the location and extent of fishing hamlets and plans to accommodate their housing needs within larger coastal development.

Fisherfolk unions also complained that the maps and the plan were not released fully in Tamil, and questioned what use the hearing would be if none of the attendees can even read the plan to be deliberated.

Read more: Nine incinerators planned for city; it’s time to pause and rethink

‘Real Consultation’ and the perception of the public

“If they told us about these things, I would find a way to adjust our schedule and go somehow. In matters that have so much public money at stake, they would want to manage the whole thing on their own, and not speak to those really affected by these projects and so they don’t invite us,” says Velayudham.

In its current form, the public consultation process is marred by an attempt to manufacture and force a favourable consensus towards the projects in question with gaining insights into genuine public opinion losing importance.

In addition, attempts to avoid the public hearing altogether reveal an attempt to avoid the public and potential opposition that comes about when people are made part of the decision-making process.

What does the public then represent to the state and its private partners?

Nityanand, in a chapter in the book Participolis titled, “No Public in Public Consultations” explains this by premising how the decision-making and consulting on a project is done between the state and the corporate actors first, a decision that he considers as the ‘real consultation’.

The second proposition is that actors of the state, probably even among NGOs, tend to be petrified by the prospect of public participation. The public who might lose their homes or lands in the process, pose a threat to such a pre-arrangement. In this line, people become a nuisance, disorderly and unreasonable, who act as an impediment to the shared interests of the project proponents, as well as speedy and efficient governance.

However, legal mandates and global expectations of participatory governance, as well as concerns of political patronage, apply pressure on the state to hold social audits and public hearings.

“The state tends to react by attempting to control and limit public participation, playing a number of tricks to avoid or thwart the whole purpose of public participation,” says Nityanand.

Force, intimidation, chaos, and withholding of information, are some of these tricks.

While some of the projects such as the Waste to Energy Incinerator project in Perungudi and Kodungaiyur were put on hold, it was due to widespread public dissatisfaction. But such outcomes take place despite and not because of the platform afforded by public consultations.

While public consultations are often deemed democratic or benevolent in intention, such instances show that they in fact have a long history of undermining the public.

**Errata: This sentence has been changed from the first published version following a clarification/correction by the source quoted.