The sounds of Carnatic music on the radio fill a cramped room painted blue in a small lane of Mylapore. Photos of Hindu deities adorn the walls, and pieces of jackfruit wood and leather are strewn on the floor. Jesudas Anthony and his son Edwin Jesudas are working in this room, sitting amid hammers, nails, a wooden peg for tuning and castor oil for polishing. Outside, temple bells resound in this old residential neighbourhood of central Chennai.

The two master craftsmen make the mridangam, a drum used as an accompaniment in Carnatic (south Indian classical) music. “My grandfather’s father started making mridangams in Thanjavur,” says Edwin, referring to the old town 350 kilometres from Chennai. His father looks up and smiles, then continues punching holes around the edges of two circular leather cutouts. He then stretches the two pieces and binds them to the open ends of a hollow frame with thin leather strips. Thicker leather straps are also stretched and twined from one end to the other, across the instrument’s ‘body’ or resonator. The entire process of making a mridangam (they work on more than one at the same time) takes around seven days.

A wooden stick and stone are used to regulate the instrument’s pitch. Pic: Ashna Butani/People’s Archive of Rural India

The family purchases the frames from a woodworker in Kamuthi town, around 520 kilometres away; it is made using dried jackfruit wood, whose fibrousness and small pores ensure that the instrument’s pitch doesn’t alter even with changes in the weather. The cow leather is bought from Ambur town in Vellore district.

When we meet him, Edwin is crushing the stone found on the riverbed of the Cauvery in Thanjavur district. The crushed stone, along with powdered rice and water, is applied to the leather at the two ends of the kappi mridangam. It makes a tabla-like sound and Edwin’s family is known in Chennai’s Carnatic music circles for their craftsmanship of the kappi. (The kutchi mridangam has a a thicker wooden frame with small strips of bamboo placed near its right end to produce a more prolonged sound.)

A newspaper article about Jesudas when he was younger that speaks of his work and legacy. Pic: Ashna Butani/People’s Archive of Rural India

Another article in Tamil pasted on the wall talks about the skills of this family. Pic: Ashna Butani/People’s Archive of Rural India

They have won awards for their meticulous craftsmanship. Pic: Ashna Butani/People’s Archive of Rural India

The right head of the instrument, karanai, is made of three layers of different kinds of leather – an outer ring, an inner ring and a portion that contains the black circle in the centre. The left head, known as thoppi, is always half an inch bigger than the right side.

Jesudas, 64, and Edwin 31, make 3 to 7 mridangams every week during the annual Margazhi music festival in December-January, and around 3 to 4 a week the rest of the year, in addition to repairing other instruments. They earn between Rs. 7,000 and Rs. 10,000 for each mridangam. Both work seven days a week – Jesudas from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. and Edwin in the evenings after he returns from work (he prefers we don’t mention any details of his job). The family workshop is a 15-minute walk from their house.

Edwin has a day job, but in the evenings and on Sundays, he works with his father at their workshop. Pic: Ashna Butani/People’s Archive of Rural India

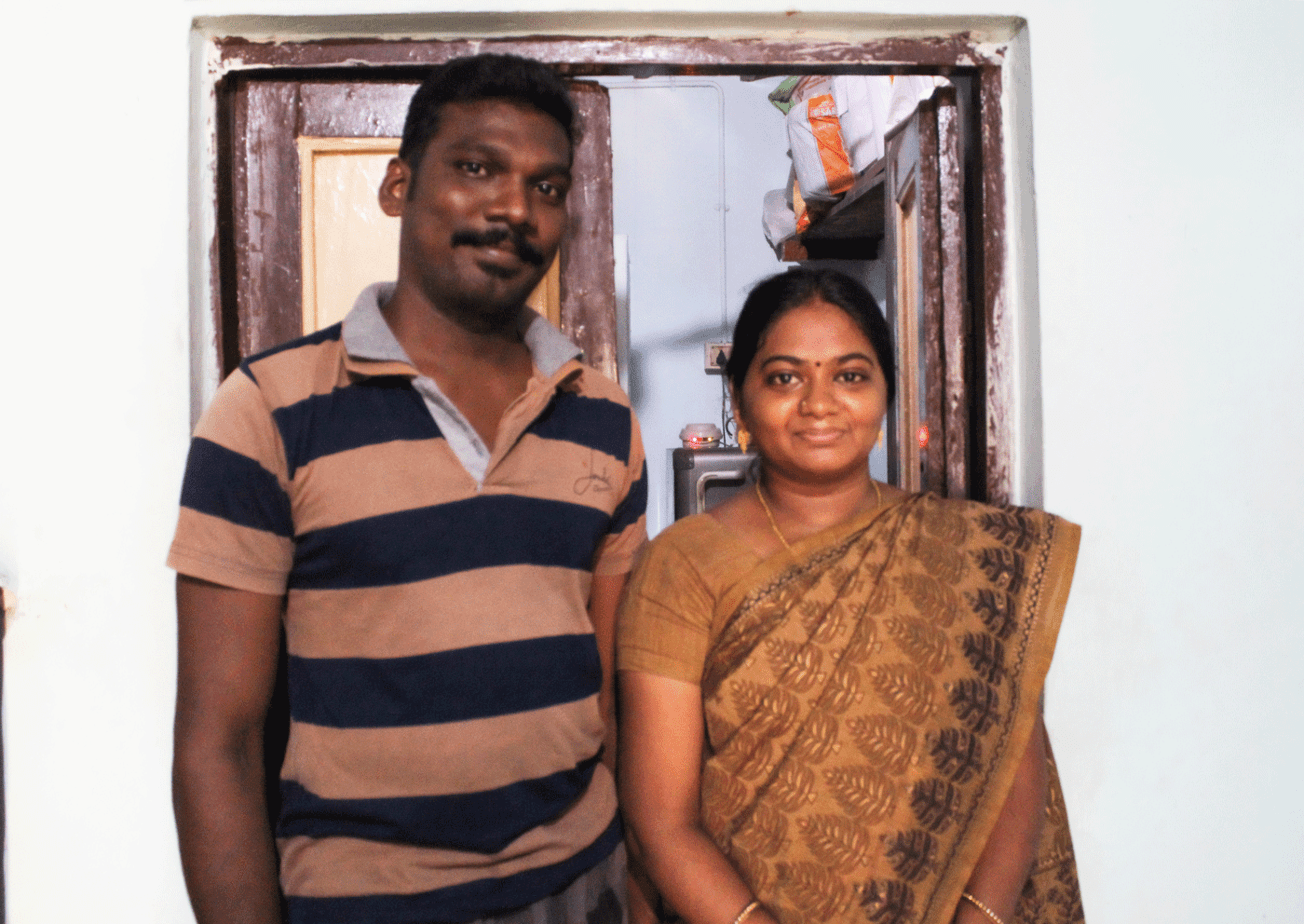

Edwin’s wife Nancy, 29, a homemaker, broadly knows how the mridangam is made, but this work is reserved for the men in the family. Pic: Ashna Butani/People’s Archive of Rural India

“We are continuing this legacy though we are Dalit Christians,” Edwin says. His grandfather, Antony Sebastian, a well-known mridangam maker, was praised for his work by Carnatic musicians, but not given respect as a person, he recalls. “My grandfather made and sold mridangams, but when he would visit the homes of clients to deliver the instrument, they would refuse to touch him and leave the payment on the floor.” Edwin feels the caste problem “is not as bad as it used to be 50 years ago,” but adds, without elaborating much, that discrimination does persist.

When he tunes one of the mridangams he has made with his father, his keen sense of sound is evident. But, Edwin says, he was denied training in playing the instrument because of his caste and religion. “Maestros used to tell me that I have a musical sense. They said my hands are fit to play. But when I asked them to teach me, they refused. Some societal barriers are still present…”

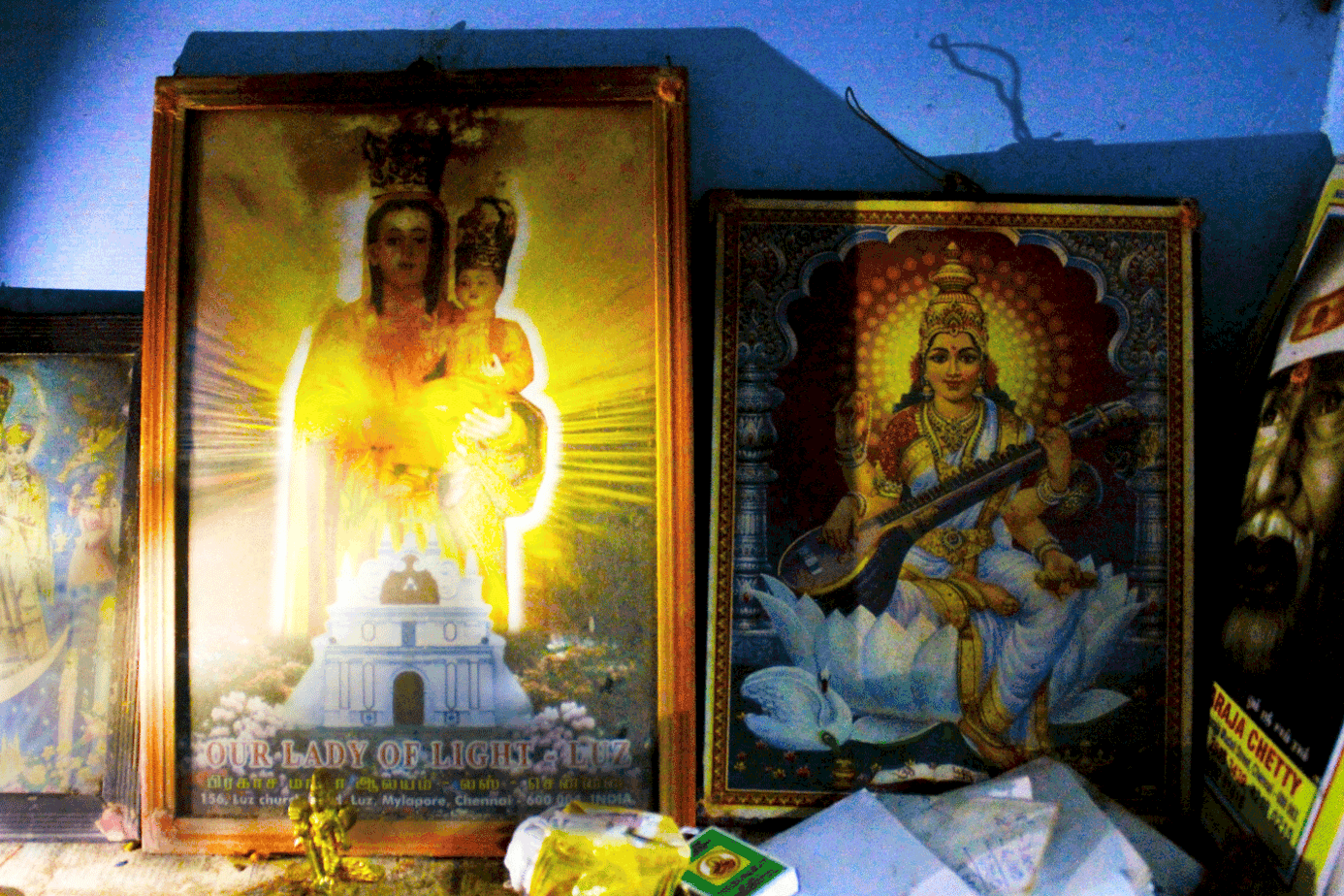

Carnatic music is largely an upper-caste Hindu preserve and though Jesudas and Edwin are Dalit Christians, their workshop has images of Hindu deities on the walls. Pic: Ashna Butani/People’s Archive of Rural India

The entrance to their home is adorned with their own community’s iconography. Pic: Ashna Butani/People’s Archive of Rural India

Edwin’s family works with a predominantly Hindu upper-caste clientele of distinguished Carnatic musicians and this is reflected on the walls of their workshop, which are adorned with images of Hindu deities, though the mridangam makers are members of the Luz Church of Our Lady of Light, Mylapore. “I know that my grandfather and his father were Christians. Before them, the family was Hindu,” Edwin says.

Despite being denied training by the maestros to play the mridangam, he is hopeful the future will be different. “I might not be able to play the instrument,” he says. “but when I have children, I will make sure that they do.”

(This article was originally published in the People’s Archive of Rural India on May 23, 2019)