In an article in LiveMint, ‘Of plagues, people and the everlasting impact of short events’, Anurag Behar, the CEO of Azim Premji Foundation writes, “We have not dealt with anything like this before, individually or collectively as a modern global society.” The article begins with a reference to William McNeill’s book on epidemiological history, Plagues and People that discusses the influence of diseases on the course of humanity. Behar writes about his chance encounter with this book at a Washington DC book store just a month ago and the turn of events thereafter. As I read this article, I think about the plague that hit Bengaluru in 1898 and a recent research exercise that we undertook.

Over the last few years, our research on tree worship and urban space had taken us to several temples in the city where Mariamma, commonly referred to as the Plague goddess is worshipped. Shown here (in the image) is the Bisulu Mariamma temple and Ashwath Katte at Dodda Mavalli in Bengaluru, October 2019. We had learnt from Janaki Nair’s book: ‘The promise of a Metropolis: Bangalore’s twentieth century’, that at the time of the 1898 plague, the British administrators had proposed a new, model hygienic suburb, Basavanagudi with better sanitation facilities. It is believed that during this time, many temples dedicated to the plague goddess were built in and around Basavanagudi and later, in Malleswaram. Around ten days ago, there was an active exchange going on about the 1898 plague at the Facebook page: Bangalore: Photos from a Bygone Age where one of the members had posted: ‘Could old Bangaloreans describe how the situation was during the plague.

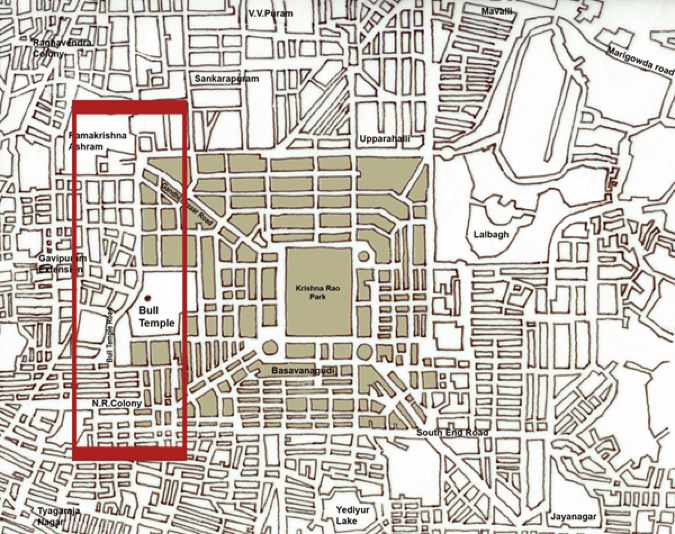

What could be the reason for this particular site having been chosen for this NEW suburb?

During our research work, we had been regularly visiting the Bisulu Mariamma shrine in the neighbourhood of Dodda Mavalli, which lies to the immediate north of Basavanagudi. In Kannada, ‘Bisulu’ means sunlight and it is said that the goddess derives her strength from the sun and must, therefore, always be housed in a shrine that is open-to-sky. The belief that sunlight prevents the formation of bacteria and viruses, endorsed the faith in this goddess as the remover of disease.

The focus of our research funded by a grant from the Azim Premji University had been on ‘the Ashwath Katte as a sustainable urban space’ – how through the practice of tree worship, people both generate and sustain these community spaces and how they work as religious and social spaces. The initial outcome from this project is now published as: ‘The Sacred and the Public’.

Ashwattha is the Sanskrit word for the Peepul tree (Ficus Religiosa) and the platform around it is locally called the Katte.

At the time of our fieldwork, and later, as we analysed the data, we had not paid much attention to the Plague goddess part of the story. However, it seems now that we may need to probe a bit more into,

- WHY the “Bisulu Mariamma” was being worshipped;

- WHAT were the rituals performed to appease the goddess; and,

- HOW could we learn something from the social and cultural habits of those times?

In cultures across the world, there have been similar beliefs and rituals related to the disease. For instance, in Chinese folk religion, Wen Shen is known to be the deity or a group of deities responsible for illness and the plague. In the book, ‘Saving lives in wartime China: How medical reformers built modern healthcare systems amid war and epidemic’, one reads: “Yet the question for the people was, why abandon a cult such as that of Wen Shen that was rooted in popular culture and that seemed to have its own way of controlling disease? It’s rituals promoted fasting, interrupted social commerce, and required people to stay at home and keep their doors fastened against entry by evil spirits.”

Today, in these times of COVID-19 as we stay in self-isolation, we seem to be following a similar routine. The difference now is that scientists the world over are going to be working hard until a vaccine is found for COVID-19. Science will come to rescue us, but until then, the “rituals” of the past have become the “lockdown” rules of today. It would be interesting to understand how some of this might have relevance for the design and planning of our cities today. Sharing these thoughts so that those of us who are intrigued by HOW CITIES WORK and who would like to explore this further, can discuss this more.