For the last ten years, Sunita Sutar has been looking after the well-being of slum dwellers near Bandra (West) railway station. From September 26th to October 12th, Sutar and nearly 4,000 Community Health Workers (CHW) like her were on the ground conducting door-to-door tuberculosis and leprosy survey for the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation’s (BMC) health department.

The survey is part of India’s plan to eliminate TB and leprosy by 2025 and 2030 respectively. It covered over 49 lakh people in 9 lakh houses across 24 wards under BMC. “When this area was initially assigned to me, it was difficult to navigate. But I can now draw the entire map of this place within minutes if required,” says Sutar.

She shares the same level of familiarity with the residents of the area. This enables CHWs like her to collect crucial health data for stigmatised diseases like leprosy with ease. There is a set line of questioning that they follow during the TB and leprosy survey. They first ask about the number of people living in the house and then list out a range of symptoms.

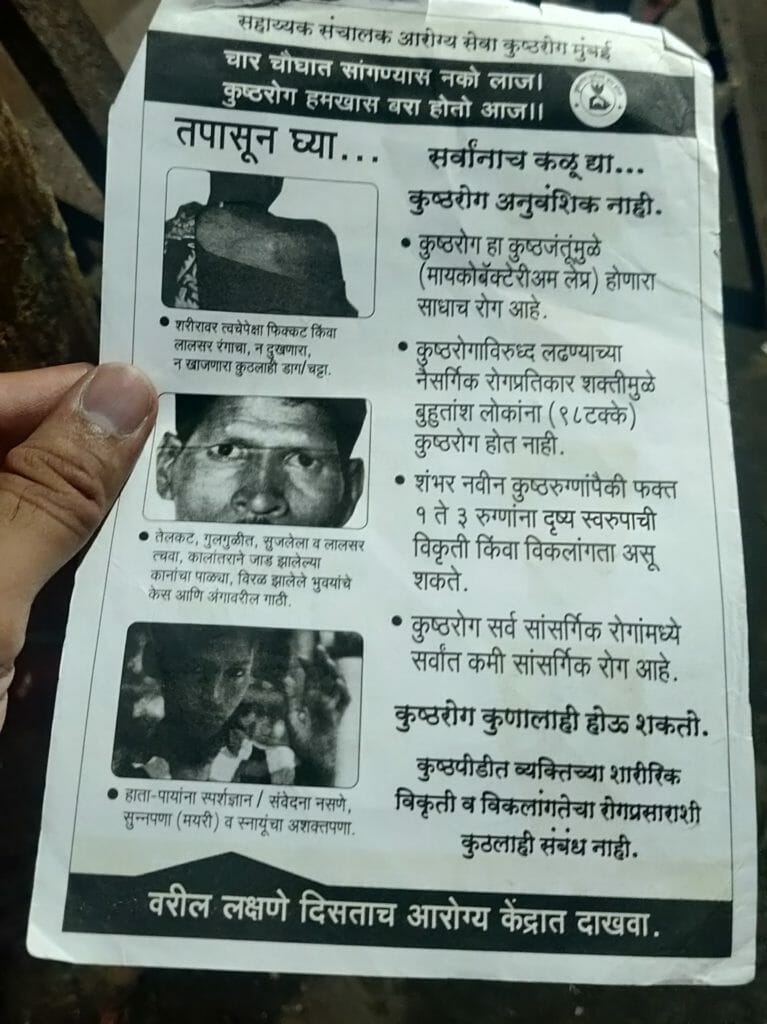

To detect TB, a person is asked if anyone in their family has a cough, fever or swelling around the neck. For leprosy, a person is given a pamphlet with a pictorial representation of the disease and asked about skin patches.

When case is detected during TB, leprosy survey

Medical superintendent of Acworth Municipal Hospital for Leprosy, Dr Amita Pednekar says, “Usually leprosy patients do not notice their symptoms. It is a chronic disease, sometimes a patient might have a single patch and other times they may not show any symptoms.” Acworth is Mumbai’s only specialised leprosy hospital.

Sutar has never come across a case that was confirmed for leprosy by medical professionals. However, her co-worker recently reported a case of that was a confirmed leprosy patient. “The suspected leprosy cases I have come across turned out to be other skin diseases. But I have come across many TB patients,” she says.

Read more: How BMC takes care of public health when it rains

A person is asked to visit the nearest leprosy or TB out-patient-department (OPD) when suspected of the disease, Sutar says. “If there is reluctance to visit a hospital, we arrange for doctor’s visit to their home,” she says.

Meanwhile, director of the Bombay Leprosy Project (BLP), an organisation working to eradicate leprosy since 1976, Dr Vivek Pai says counselling of patients is essential and so is providing accurate information about the disease. “This needs to be done during the course of the treatment services and follow up care so that the compliance of the patients is adhered to for better health outcomes,” he says.

The pandemic impact

Leprosy cases in Mumbai remained between 400 to 500 in the pre-pandemic years. They fell significantly in 2020 and 2021 as the focus on coronavirus impacted leprosy surveillance. However, a large number of cases were reported earlier this year. Between April and August, the city recorded 236 leprosy cases, which is close to the total cases (335) detected in 2021. Officials told the media that the jump in the cases is because of a large backlog of missed detections.

“COVID-19 pandemic impacted all disease surveillance including leprosy so notifications during last the two years were very less. From this year, we are steadily coming to a pre-COVID situation,” BMC’s executive health officer Dr Mangala Gomare says.

Dr Pai also shares the drop in leprosy patients BLP witnessed in the last two years of the pandemic. “There was a decline in the new referrals for clinical problems such as reaction, nerve damage, disability care,” he says. A large number of leprosy patients are referred to BLP by other medical practitioners and institutions.

On the other hand, there was a disruption in the detection of TB cases only in the first year of the pandemic. In 2019, a total of 60,597 TB patients were identified in Mumbai but this number fell to 43,464 in the year 2020. In 2021, disease surveillance picked up and the city reported 58,642 TB cases—matching up to the pre-pandemic trend.

The cost of TB and leprosy survey

CHWs take personal health risks going door-to-door in densely populated areas like slums, where communicable diseases spread faster. Every day, they cater to 60 families for a monthly stipend of Rs 11,000. However, during the 14-day TB and leprosy survey, they are asked to cater to 25 additional homes daily for Rs 75 per day from the state government.

“This is extra work we are required to do alongside our daily duties,” Sutar says. Until last year, the CHWs received Rs 50 from the BMC as well for the survey, taking the 14-day total income to Rs 1,750. “So it used to be Rs 75 plus Rs 50 but this year BMC stopped that. As per the rules, we are supposed to be carrying out a TB and leprosy survey with another male CHW. But no man wants to do this work for such low pay,” says Sutar.

However, Dr Gomare believes the compensation is fair for the number of houses they survey. “Rs 75 for 25 houses is not less. We have told them that they can combine two-day work and survey 50 houses in one day and earn Rs 150 instead.”

Many CHWs had refused to start the survey demanding better pay. “The BMC only gave us verbal assurances, no notification came in that regard,” Sutar says.

In the absence of a male volunteer, she surveys everyone and not just the women. She travels in and out of the small, narrow lanes of Bandra West slums and talks to anyone who opens the door. When a house is dimly lit and feels unsafe, Sutar calls the residents on the brighter side of the road for further investigation of their health. “Many retired CHWs are forced to beg. We lack social security,” she says.