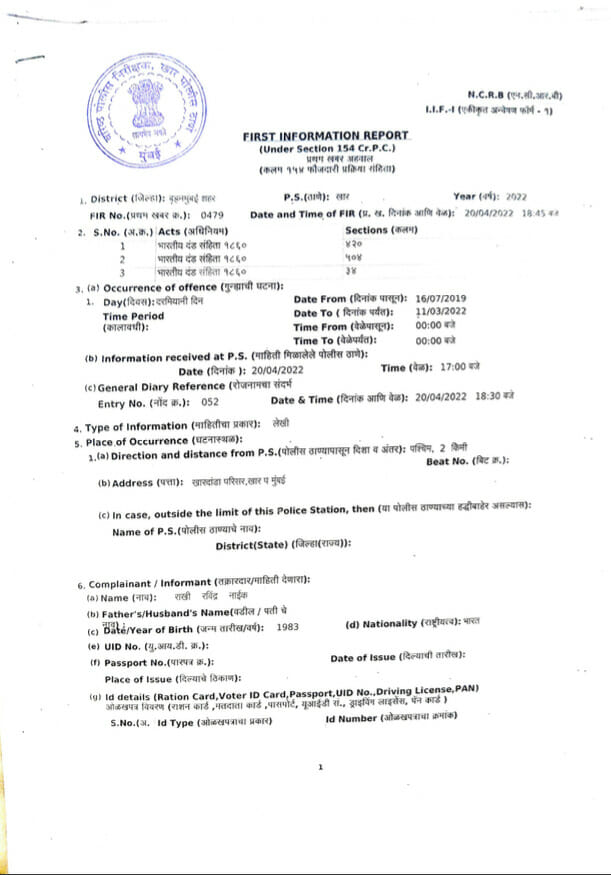

In August this year, Rakhi Naik, a domestic worker in Mumbai, was found pleading to the police at Khar police station by Aftab Siddique, a teacher and social activist in the city. Rakhi was on one of the many rounds she had made to police stations asking for help after filing an FIR in April. Through Rakhi, Aftab was able to unravel a complicated pattern of fraud in the city. Men claiming to be brokers and agents dupe people from the lower class out of lakhs of money and make affordable housing harder for them.

It all started when Rakhi signed an agreement on July 16th, 2019, with one Diwakar Sahadev Rane, whom she was introduced to by Sachin Jadhav, a witness in the agreement. “When I came from Nalasopara to Bandra (six years ago), I stayed at a place behind Ram Mandir. After three years my agreement ended, and during my search for another house, I found Sachin,” says Rakhi. Citing issues with the landlord of the house behind Ram Mandir, in a desperate state she met Sachin who claimed Diwakar was his boss.

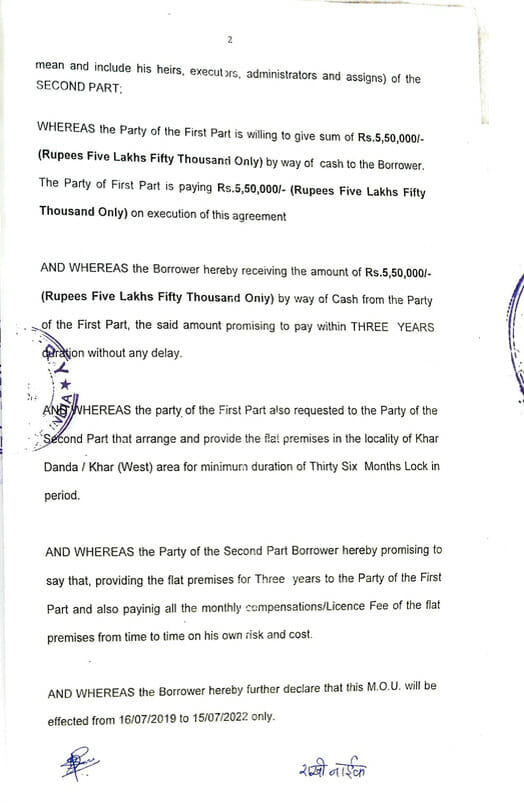

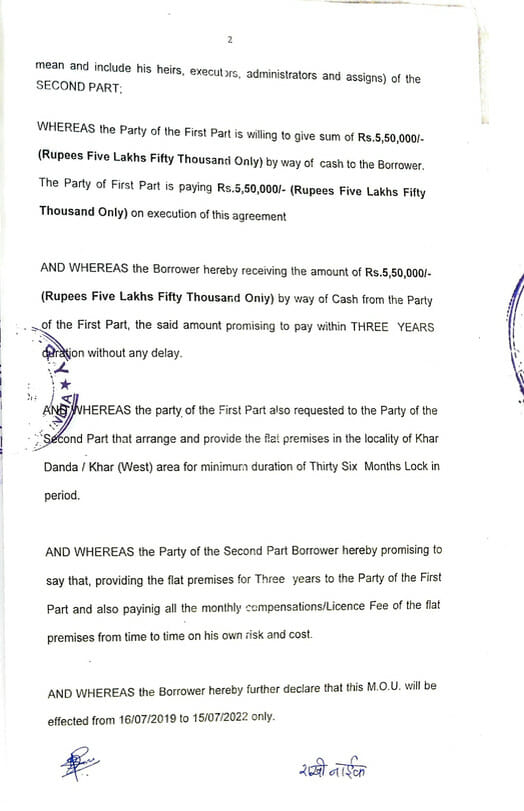

Rakhi deposited an amount of Rs 5,50,000/- which, she was told, would be compensated to her after three years. In the meantime, Sachin and Diwakar would pay the monthly rent of Rs 15,000/- of a flat that they would provide, in a Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) building. The plan worked for two years and Rakhi and her two sons had a home, so she did not see any reason to question it. But during the lockdown, the payments suddenly stopped, and Rakhi was under threat of eviction. She never got her money back either.

Affordable housing an impossible dream

Rakhi hails from Mumbai, and before moving to Bandra, lived in Nalasopara, where their home was in terrible condition, with basic amenities missing. Rakhi would travel to Bandra, Khar every day for work, leaving home at 5 am and reaching late evenings. Her elder son was studying hard to be able to pursue a degree in Hotel Management from Pune. Her husband, she says, was out of the picture for six years on account of an alcoholic period that landed him in serious physical injury. He is now back but physically challenged. “My husband troubled us a lot. I did not want my sons to go down his path, so I fought for us to move so that they could study,” she says. At one point, her eldest son travelled from Mumbai to Pune every day to give his exams.

Read more: Why ‘affordable housing’ is just a myth in Mumbai today

Aftab met Rakhi by accident. She was at the police station that day for a different matter. “She (Rakhi) was crying before all the officers, saying she has been running from pillar to post from April and she has not been heard. One of the officers told her to go to me for help. I told them, am I supposed to do your job? But I browsed her papers and was shocked to see what had happened. To that date, there was no help from the police,” says Aftab. She pushed Rakhi to start talking about her plight with others, while Aftab also took to social media to share this case, and through these efforts, Aftab was able to collect 28 such cases in the city. All women, different fraudsters.

Sangeetha, a domestic worker, was put through the same ordeal. She met Sachin Jadhav through Rakhi. “He (Sachin) did not tell us that the agreement would be made in his name,“ says Sangeetha. In all cases, the pattern is the same – the promise of a home amid turbulent conditions for the seeker, the demand for a hefty deposit with vague verbal explanations, and ultimately, fraud, resulting in futile attempts for justice. Another woman known to Rakhi was caught in the same situation. Shainali Shekhar paid Sachin a sum of Rs one lakh after Rakhi introduced her to Sachin. Rakhi says Shainali is not talking to her anymore.

Aftab expresses anger towards the police over handling of this case. She was forced to file a civil case, when, according to Aftab, the case is uniquely criminal in nature. A civil case takes longer than a criminal case, and requires lawyers, time and labour, none of which Rakhi can afford. “The criminals are running scot-free. These women are at the mercy of the system that does not care,” says Aftab.

A senior inspector at Khar police station, who did not wish to be named, confirmed the ongoing investigation by stating that Diwakar was arrested at the time the FIR was filed, but got bail. “Right now the statements of three women are being registered,” he said.

A complicated legal battle

Advocate Vinod Sampath feels that, legally, this is more complicated. “Once an FIR is filed, then a chargesheet has to be filed. Inevitably, the police delay filing the chargesheet, because right after that is done, there is a lot of running around. It has also happened that after filing an FIR people lose interest in the case. So the police, to avoid the extra work, doesn’t want to file a chargesheet. Now here, Rakhi cannot do more than what she is doing. If the police are not handling the case properly, then she can go to the senior inspector which she has already done. Beyond this, what is left is the civil case in court, which can go on and on. The money will not come back anyway, at most, a sentence will come,” he says.

He adds that for her to take this case further, she can file that the money – Rs 5 lakh for deposit – was paid for the sake of livelihood. This in itself makes it liable for the Consumer Court, where she can a file a case for deficiency of services and unfair trade practices. Over there, if the money is not paid back, the case can be dealt with criminally.

However, Advocate Sampath also pointed out that Rakhi could be found equally at fault, because she agreed to the arrangement in the first place.

Aftab in response outlines how this is unique to marginalised communities. In the absence of support from the system, decisions are made out of desperation, faith, and the lack of basic amenities in their price range. “These are people always on their toes, through the day. Wherever they get work, they take it. Whenever they get help, they grab it. This is also not just about one woman, there are so many others, so many of them single mothers who cannot read English. If they are given the promise of a home, why will they fight it?”

In Mumbai, where real estate is scarce, precious and over-priced, affordable housing is inaccessible to most of its citizens. Scores of people – of all socioeconomic classes – come to the city for a better livelihood and are desperate to find a roof over their heads in a short time. Despite laws requiring registered agreements, digitised processes and so on, more often than not, it is the brokers and agents who play the role of the mediator, and facilitator for citizens who are unable to work the system officially. Lack of experience, knowledge and desperation makes them heavily dependent on these agents, who claim to work the system for a fee.

None of this is documented in legal agreements. (Agreements with owners are, but money exchanged with brokers is rarely officially recorded). Tenants have no choice but to trust the agents. These arrangements work – brokers and owners get money and tenants get a place to stay without having to go through tedious systems. However, in cases of fraud or duping, the tenants have nowhere to go and no system to rely on. While the officials of housing authorities and the police do look into the matter, the affected tenant has to find another accommodation in almost a similar manner, all over again, making this a never-ending cycle.

What is the future of affordable housing in Mumbai?

In 2018, the central government announced the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) initiative to provide affordable housing to the urban poor by 2022, now extended to 2024. But with the real estate market favouring luxury buildings over housing the lower class, the government’s promise seems impossible to achieve. In Mumbai itself, many say affordable housing is easier to accomplish than people are led to believe.

In the meantime, the Maharashtra government has seemingly seen some development where their goal of affordable housing is concerned. In 2019, there was talk of combining many agencies – Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA), Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) and some departments under the Urban Development Department – to expedite affordable housing.

The MHADA was established in 1948 to construct residential properties for people of different demographics. As per the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana plan for 2022, Maharashtra was meant to construct five lakh affordable houses in the state by this year. Not much is known about the update, except that on September 16th, the newly appointed Shinde-Fadnavis government restored the powers of MHADA by issuing a government resolution (GR) that will now allow the Authority to make decisions on its own without government intervention.

It is yet to be seen how this will play out since, on the ground, citizens like Rakhi, who take on the financial burdens of the family without an educational background will continue to depend on Sachins and Diwakars of the system.