Our cities, today, appear doomed under the threat of the dreaded coronavirus. Faced with a ‘novel’ virus, researchers have been continuously trying to keep pace with its various mutated strains, and come up with proven ways of transmission, prevention and cure. In studies related to the first, a team at Florida Atlantic University’s Department of Ocean and Mechanical Engineering has found that public toilets, with cramped spaces, heavy foot traffic and inadequate ventilation, could be a hotbed of spread, as flushing a toilet generates large quantities of microbe-containing aerosols (depending on design, type etc).

COVID risk in public toilets

In fact, several studies underlining the risk in public toilets have been published over the last one year.

A joint paper on ‘Aerosol and surface stability of HCoV-19 (SARS-CoV-2) compared to SARS-CoV-1’ published in medRxiv on March 20, 2020, by the US Government, specified that “viable virus 36 could be detected in aerosols up to 3 hours post aerosolization,… and up to 2-3 days on plastic and stainless steel.”

Most toilets use a combination of ceramic and steel for the plumbing fixtures, while hand dryers are usually made of plastic. Physical handling of doors while opening and closing them was another area of concern discussed then.

An article, ‘Public Restrooms and COVID-19: Guidelines for Reopening’ published in Publish Hygiene Let Us Stay Human (PHLUSH) on June 29, 2020, again highlighted how such facilities could put users at risk:

- COVID-19 spreads not only through respiratory droplets which quickly fall to the floor, but through aerosol particles which remain suspended for much longer.

- Viable SARS-CoV-2 virus has been shown to survive in stool, bringing risks of fecal-related contagions.

- Flushing lidless toilets typically found in restrooms sends vertical plumes several feet into the air.

- Forced-air hand dryers propel microbial material from inadequately washed hands into the surrounding spaces.

- Partially paneled restroom stalls bring bathroom users into close proximity within poorly ventilated spaces.

- Bathrooms also have multiple touch points – stall door locks, flush handles, and faucets, which put users to additional exposure.

In the latest research by the team of scientists in Florida, one of the co-authors has been quoted in a media report as saying, “After about three hours of tests involving more than 100 flushes, we found a substantial increase in the measured aerosol levels in the ambient environment with the total number of droplets generated in each flushing test ranging up to the tens of thousands.”

In the present conditions, given that several fellow restroom users are likely to be pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic, who can unknowingly transmit SARS-CoV-2 virus, not only availability and accessibility of public and community toilets but also their effective sanitization has become paramount. As per PHLUSH, “It’s clear that shared restrooms need to be managed with care during this pandemic.”

But have we really ever paid public toilets enough attention in Indian cities?

Read more: What did the audit of public toilets in Chennai reveal?

Our public toilets: What the Swachh Bharat Mission envisioned

The unprecedented migration from rural areas to cities and towns over the last three decades has caused severe strain on the existing public infrastructure. Access to clean sanitary facilities is one of the challenges of a fast-growing urban India.

The Swachh Bharat Mission – Urban (SBM-U), launched at Raj Ghat on October 2nd, 2014, aims at making urban India Open Defecation Free (ODF) and achieving 100% scientific management of municipal solid waste across 4,041 statutory towns in the country. As per the SBM, “A city/ward can be notified/declared as ODF city/ ODF ward if, at any point of the day, not a single person is found defecating in the open.”

One of the key objectives of the mission is to enable 100% ODF status in all Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) in the country. This means that every citizen should have access to clean and usable toilet facilities, which calls for functional operation and maintenance of these facilities. The initiatives are also targeted at facilitating behavioural change of users and other key stakeholders through their intensive participation. However, the real objective can be achieved only when these sanitary facilities are used regularly.

Two of the components of the SBM-U are:

- Community toilets

- Public toilets

Public toilets are located in areas with high footfalls whereas community toilet blocks are used primarily in low-income or informal settlements/slums, where space or land (or both) are constraints in providing a toilet for every household. As per the Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation (CPHEEO), Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, GoI:

“Community toilets (CT) facility is a shared facility provided for a defined group of residents or an entire settlement / community. It is normally located in or near the community area and used by almost all community members, whereas public toilets (PT) facilities are provided for the floating population / general public in places such as markets, train stations or other public areas and used by mostly undefined users.”

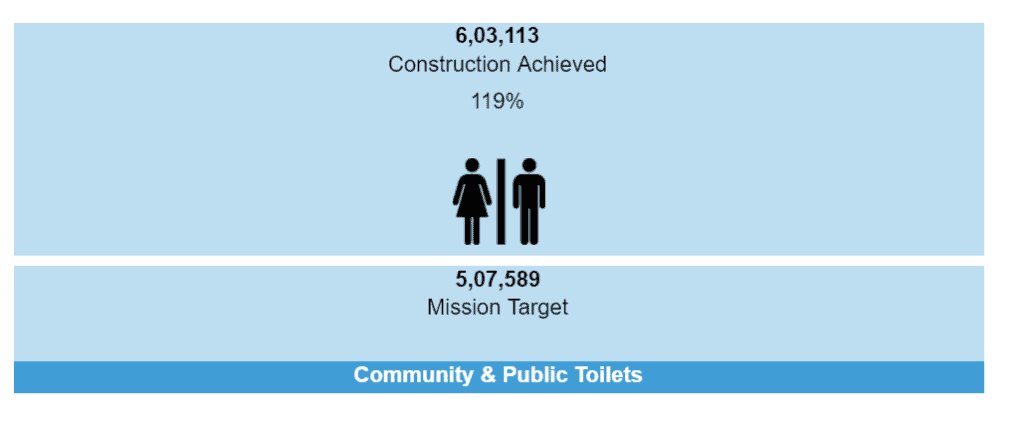

The targets set for the Mission in connection to the above two components are:

- Construction of 2.52 lakh community toilet (CT) seats;

- Construction of 2.56 lakh public toilet (PT) seats

The projected deadline for their completion was set for October 2nd, 2019, i.e. 5 years after its initial launch.

But are these numbers in themselves enough to ensure an end to open defecation or public urination, or do these facilities need to conform to certain standards for them to be useful, convenient and most importantly, safe?

Read more: How Swachh Bharat remains a poor joke in Bengaluru

Norms for toilets

The norms for the number of WCs, urinals, bathrooms and standard sizes of WCs, bathrooms, urinals and washing area in PT/CT are laid down in the guidelines for Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban), 2014. IS 1172:1993 lays down the sanitation requirements in specific urban public spaces, such as railway stations, markets, office buildings, factories, restaurants etc. These norms are also in line with the Model Building Bye-laws, 2017, MoUD.

As per the Amendment 1 (Point 11) of the ODF Protocols for certification of ULBs/Cities issued on October 11, 2018, all functional public toilets have to remain open daily at least from 4 am to 10 pm, while those situated in locations like railway stations, which have visitors/footfalls round the clock should remain open 24 hours a day.

Facilities crucial for public toilets

From a design perspective, public and community toilets should provide clean, safe, accessible, convenient, and hygienic facilities. Aspects like safety and privacy are central to toilet design but two additional key considerations controlling toilet usage are the number of seats in a toilet facility and its location.

Public toilets are commonly separated into male and female facilities with separate entrances. However, globally, where there are small or single-occupancy public toilets, one can also find some unisex ones. Unlike earlier, when there were fewer instances of women working outside their homes with lesser footfalls to public loos, safe and private public toilets have now become a necessity for a larger set of the female population. And increasingly, public toilets are also being made accessible to citizens with physical constraints.

As per the CPHEEO guidelines:

- Public toilet facilities should be located close to heavy footfall generating areas for the convenience of women, children, aged and differently abled.

- They should not be located close to places deemed unsafe for women like liquor shops, areas without street lighting or walking access, etc.

- Adequate consideration should be given to providing a clearly defined, accessible and safe pedestrian path to the facility, including ramps, lower elevation and plinth heights, height of steps, etc.

- The path must be well lit to ensure that the user’s personal safety is not compromised, particularly for women and adolescent girls.

Average cost of constructing a toilet seat/urinal

CPHEEO has identified that the average cost per WC in a community toilet facility depends on local schedule of rates, market rates, specifications, treatment technology for wastes and site condition. As per the SBM guidelines, tentative basic cost for PT / CT facility is Rs. 98,000/- per seat and urinal is Rs. 32,000/- per seat, with 40% Viability Gap Funding (VGF) from the Government of India (GoI). State assistance will be at least 1/3 of GoI’s assistance.

Effective ways for monitoring the maintenance of toilet facilities

As per CPHEEO, “Regular monitoring of toilet facilities lies with the agency responsible for it.” Some of the guidelines for their Operations & Maintenance (O&M) are:

- Facility operators should request users for feedback

- Regular review meetings by ULB

- Random weekly monitoring should include aspects such as cleanliness, availability of adequate water, status of electric power points, status of minor repairs, major repairs, waste disposal system, behaviour of staff with users of toilets, level of maintenance of building, etc.

- Monthly physical monitoring of the premises and feedback review of the users on the O&M by the local authority that provided land and financial support for the toilet facility.

Each PT facility needs to maintain a feedback register placed at the counters of toilets for easy access by users of toilets. The feedback can also be in the form of questionnaires, user feedback machines and mobile applications. In addition, CCTVs need to be installed at crowded places from both a security aspect as well as for identification of lapses by the agency in maintenance of the toilet.

Special safety requirements in view of COVID

PHLUSH has proposed the following actions to safeguard users of public toilets during the pandemic:

- Reopen public restrooms as they are crucial to the revival of economic and community life

- Understand the longevity of SARS-CoV-2 in enclosed space. Ask users to wear masks in shared toilet facilities and to exit as soon as they have finished their business.

- Fit toilet seats with lids if they don’t have them because flushing can propel aerosols with infectious virus into the restroom.

- Remove forced air hand dryers that spread virus and bacteria and provide paper towels for hand drying

- Place hand-hygiene stations at the entrance restrooms and ask users to clean hands before entering to avoid surface contamination

- Establish new restroom maintenance protocols, ensure constant ventilation, choose appropriate cleaning technologies, train cleaners, and provide signage to educate users.

Equitable and resilient public health and sanitation systems are not an option but a high priority requirement in a city. Public toilets can be a hotbed of infection, as they come with high-touch surfaces and often lidless toilets. The pandemic is here to stay. While the number of public restrooms which have mushroomed in the last couple of years is impressive at first glance, until there is a sea-change in the way these facilities are conceptualised, designed and maintained, today and even beyond the pandemic, the real needs — both immediate and long term — shall not be met. Any measure called for now should not be looked upon as a one-time panacea. They will be equally useful when we come out of the shadows of the pandemic.

Also read:

Need of the hour. Well said

Thank you, Ramesh!

Well researched article ! The pandemic is here to stay – that’s a sad but true statement. Arrangements to be made keeping this in mind – it’s the need of the hour. It’s a unique eye opener article as I , for one , hv not thought about this in the least . Kudos Madhavi

Thank you, Suchitra!

This means the indian style toilets need to be phased out.