Part 1 of this series looked at the scale at which farm produce is traded through the APMC (Agricultural Produce Market Committee) system in Bengaluru. In this part, we explore how the APMC operates, and how successful the system has been.

Yeshwanthpur APMC yard, spread across 85 acres, is one of the largest market places for farmers and buyers across the country.

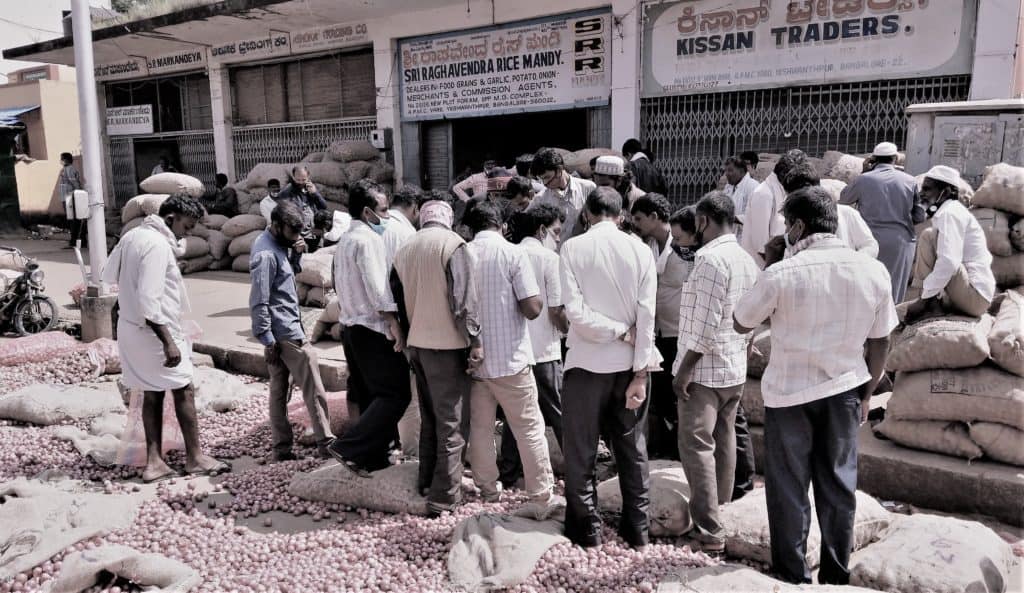

It is commission agents who play a key role in facilitating trade between farmers and buyers here, especially in case of perishable vegetables like onions and potatoes. The agents receive farmers’ produce, which is then auctioned in their shops to a handful of buyers who are retail traders or agro-industry representatives. Many agents themselves own retail stores, or are exporters.

Uday Shankar, Secretary of the Potato and Onions Traders Association here, says, “We have a relationship with farmers which ensures they bring their produce to us. And conversely, we know buyers who travel from far to bid on produce, based on the faith they have in us.” Uday’s family has been trading potatoes in the yard for more than 50 years.

The relationship with farmers is mostly built on the bedrock of loans and advances paid by the agent. Often, the agent arranges for fertiliser, seeds and financial aid for the farmer before the sowing season. After harvest, the farmer is then bound to bring the produce to the commission agent for auction, and the payment is adjusted to the advance taken.

For buyers, a commission agent’s value is in offering quality, fair price as well as occasional loans to cover their transport costs.

A farmer is charged only for the services of the ‘hamali’ (who loads and unloads sacks of produce), at the rate of Rs 10 per sack. However, agents make their living by charging a commission of 5% from the buyer for the produce sold.

Agents estimate that, on average, the market receives 20,000 bags of onions and potatoes a day, with each bag selling between Rs 600-1,500 depending on the variety, quality and market price for the day. This translates to around Rs 10 lakh per day in commission fees in total, on average. There are 1,597 licensed agents operating out of Yeshwanthpur yard.

Agents buy rice and pulses as processed goods from millers, and not directly from farmers. There is no fixed commission on these products. Instead, commission agents’ earnings come from taking advantage of the fluctuations in the market as they buy from millers and sell at higher prices to retailers and markets elsewhere.

What is the Committee’s role?

Overseeing the trade facilitation by commission agents is the APMC, an elected body that comprises representatives of farmers and traders. Bengaluru’s APMC has 15 members, of whom one is voted by the nearly 2,000 agents/traders in the region. The rest are voted by farmers from 699 villages in and around Bengaluru. The elected members then vote for the chairperson and vice-chairperson. The election and functioning of APMC is determined by the Karnataka Agricultural Produce Marketing (Regulation and Development) Act, 1966.

Elections are fought without political affiliation, but most people admit that it is the politically-connected who become chairpersons and members.

Bengaluru’s APMC body lapsed nearly a year ago and has since been run by bureaucrats. Ramesh Chandra Lahoti, President of the Bangalore Wholesale Food grains & Pulses Merchants Association, says, “Rural APMCs (in other districts) deal with farmers directly and these committees become important voices for them. But, Bengaluru is a terminal market where processed goods (rice and pulses) are traded in bulk. It is only in vegetables that farmers play a role. For the rest of the trade, the committee has little role in day-to-day functioning.”

For farmers, the committee, on paper, acts like a safety net. If a buyer fails to pay the farmer or underpays, then a complaint can be registered with the APMC. This can result in the buyer being blacklisted.

Similarly, licenses for agents and traders are controlled by the Committee which is supposed to ensure that the norms for auction, accounting and weighing of produce are followed. The Committee is also entrusted with enforcing norms of Minimum Support Prices that are announced by the government.

Additionally, the Committee administers the sprawling APMC yard and is in charge of developing and maintaining its infrastructure. APMC funds this by collecting a market fee of 0.35% on transactions within the yard. APMC officials pegged average daily turnover in excess of Rs 50 crore at the yard, which translates to Rs 17.5 lakh being collected as market fee per day.

The market fee had been reduced in mid-2020; it was previously 1% from the sale of onion and potatoes, and 1.5% from other produce. Apart from market fee, a license fee is charged from traders/agents.

Put together, Bengaluru’s APMC collected revenues of Rs 56 crore in 2018-19, of which it spent Rs 27 crore. Nearly two-thirds of the expenditure goes towards infrastructure development within the APMC while some amount goes to the state government, say officials.

Where it all went wrong

In theory, the democratic functioning of APMCs should’ve delivered fair prices to farmers. However, the system is beset by problems – from crumbling infrastructure, lack of storage godowns, to cartelisation that depresses prices and prevents licenses being given to new traders. According to the Centre’s Agriculture Market data, just 100 new licenses were given at the Bengaluru APMC between 2010 and 2020.

Commission agents have lobbied with the APMC to “consult” them before handing out new licenses.

A potato trader says, “If there are more traders in the market, then our overall profits will reduce too. We’ve also asked for an increase in the commission we can charge because our overall costs have increased. We cannot afford to lose revenue in this sort of environment.” Traders refute allegations of price manipulation.

The proponents of the farm laws recently introduced by the Centre and State have sought to highlight that these inefficiencies in the APMC system are suppressing farm incomes. Currently, there are just two private market yards for farmers in the city (in addition to other avenues such as local farmers’ markets and the government-controlled HOPCOMS).

Many marginal landholding farmers choose to bypass the APMC system altogether as the cost of logistics outweigh the benefits of using an APMC. Barely 35% of farmers in the state use APMCs and a majority of the produce continue to be sold in local markets, says Dr T N Prakash Kammardi, former Chairman of Karnataka Agricultural Price Commission.

Kammardi opines, “There is no doubt that vested interests have captured APMC functioning. Political interference has made it worse. But, it is a democratic body that can be reformed through better enforcement of the rules. If APMCs are phased out of relevance, it is the same commission agents and traders in APMCs that will take over the private agricultural market. However, this time, it will be without regulation.”

For many farmers like Dasappa from Chitradurga district, the journey to the Bengaluru APMC is often fuelled on trust and hope. His experience is that there’s little scope of getting cheated and that buyers make payments on time. Equally important is the trust in the commission agent, who loans money for the next crop or even for sudden expenses of hospitalisation.

Dasappa sums up the concerns of many farmers, “People tell us that we will get better prices if corporates are allowed to buy our produce. But can we trust these faceless entities? Can I call them when I need quick loans?”