Climatic and non-climatic factors intersect and create an entire tribe of marginalized and vulnerable people. Incidentally they form a large proportion of the informal economy of Bengaluru and other cities.

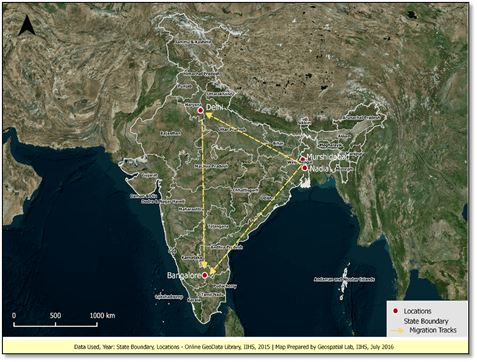

This photo essay looks at the living and working conditions of one of the most marginalized groups in Bengaluru namely the waste pickers. The focus is on those who live in undeclared, blue tent, temporary squatter settlements. Our field research revealed that most of the inhabitants in these settlements are migrants from West Bengal, a distinct region in the East of India.

For the residents of the informal settlements that we visited, migration from West Bengal has been an outcome of both push and pull factors. The major push factors have been climatic events like floods and cyclonic storms, particularly the cyclone Sidr in 2007. The migrants are typically landless agricultural labourers who have suffered from the agrarian distress and social and economic marginalisation. Relatively abundant livelihood opportunities in big cities like Delhi and Bengaluru act as major pull factors for these migrants; particularly in the context of poor life experience in their native location.

The lure of the big city

Bengaluru as a growing economy offers livelihood opportunities to many. The poor and marginalized resort to work in the informal economy since the formal economy has several entry barriers. The informal sector, especially in construction and waste picking, proves to be a feasible opportunity for the poor and marginalised, since there are less entry barriers like education attainment or skill and no need for any formal training.

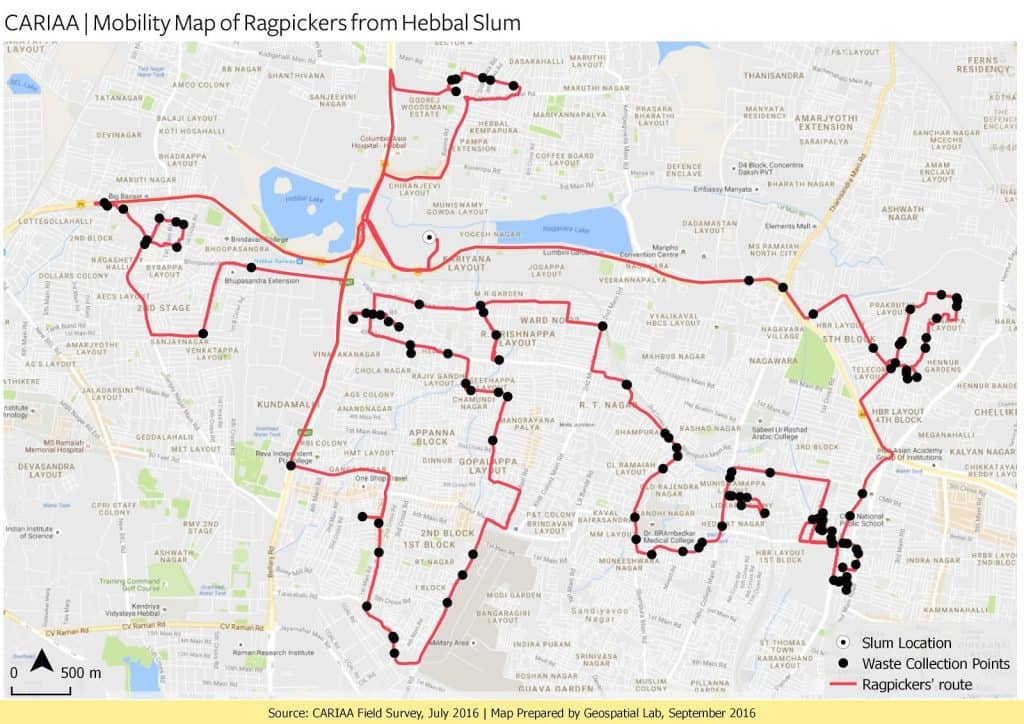

The map above illustrates routes covered by a waste picker on his cycle in a span of three days. Waste pickers provide an essential service by driving the city’s recycling efforts, keeping the streets clean especially in areas not covered by the local government. They are vital for the effective functioning of an urban system. However, this is a dangerous, and discriminatory livelihood, where as waste pickers they are typically invisible in the eyes of the city.

Climate change impacts their livelihoods mainly during the rainy seasons and summers. During the rainy seasons their waste gets soiled as they have no storage facility thereby affecting their income.

The grass is not exactly green on this side

Bengaluru has witnessed highly exclusionary urbanization patterns — rising price of land and rentals have made housing a major issue, resulting in a significant proportion of the city’s population living in informal settlements (notified and non-notified) scattered throughout the city. The city is thus unable to absorb the surge of migrants.

Unfortunately, the poor have to live in temporary settlements with no form of tenureship or rights over the land. These settlements are cut off from basic services and infrastructure such as networked water supply, central electricity network/grid, with no sanitation and waste disposal facilities. Their dismal living conditions and livelihood results in mal-recognition and further marginalization by the city.

The burdens of the invisible masses

As waste pickers, they are exposed to hazardous and toxic material. They suffer from headaches, dehydration and fatigue as they travel in the scorching heat to collect waste. This group is among the most vulnerable groups noticed in the informal settlement scoped in Bengaluru as they are at the bottom of the hierarchy of the informal economy, represented by the quiet violence of neglect, disdain, ill health and uncertainty.

The unknown variable in the equation

Climate change in the urban centres has very subtle impacts and it is difficult to distinguish between risks that are an outcome of improper urbanization and risks arising from climate-induced events. Climate change acts as a crisis catalyst and shapes and reshapes existing vulnerabilities.

The effects of climate change fluctuates among different social groups and often falls disproportionately on the poor and socially and economically marginalized such as waste pickers as highlighted in this.

A choice between two injuries

Thus, the moot question for these unfortunate migrants becomes: Destitution in their homeland, or injured identities and perilous livelihood in a bigger, thriving city such as Bengaluru?

Authors: Tanvi Deshpande and Kavya Michael

Photo credits: Shamala Kittane, Nilakshi Chatterji, Saideepa Kumar, Kavya Michael and Tanvi Deshpande